What do you call the southmost part of Tulsa’s downtown? I’m legitimately curious, unsure if there’s an answer or even anyone who cares to contemplate the question. A nameless place is weirdly refreshing these days. Place names are plentiful yet frequently rootless. Sometimes they’re a speculative wish for what a neighborhood might become; elsewhere, they’re dripping with exaggerated nostalgia for a long-gone past.

An example is my Aunt Norma bragging about the “historical” accolades of her Dallas-Fort Worth suburb’s restrained downtown. It’s easy to scoff at, but she’s right. In this geographic context, anything older than Grapevine Mills Mall is indeed historic, worthy of district designation.

In Tulsa, our naming conventions are equally fluid, frequently aspirational, and downright manic, especially downtown. Few other cities rival our ratio of districts to downtown blocks. In the early 2000s, downtown was a sea of vacancies before pioneers like Libby Billings of Elote and Elliott Nelson of McNellie’s Group set up shop; today, the boundaries between our Deco, Blue Dome, and Arts Districts are blurry at best. If these districts are no longer distinct, it’s because Tulsa’s outgrown that era and fulfilled expectations that the blocks around these outliers would bloom.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter, The Talegate

Looking north on Boston Avenue, you see Tulsa as it is: a modest metropolis. Looking the opposite direction, the imagination conjures little. South of 5th Street, there’s a sort of patchy area, a peri-threshold of semi-convincing buildings that house the threatened species known as full-time office workers.

Further south of there, though, is where density falls off completely. Parking spaces in this area vastly outnumber full-time residents. Churches with dwindling congregations are selling off property, and the few remaining, underoccupied apartment buildings appear as molting monuments.1

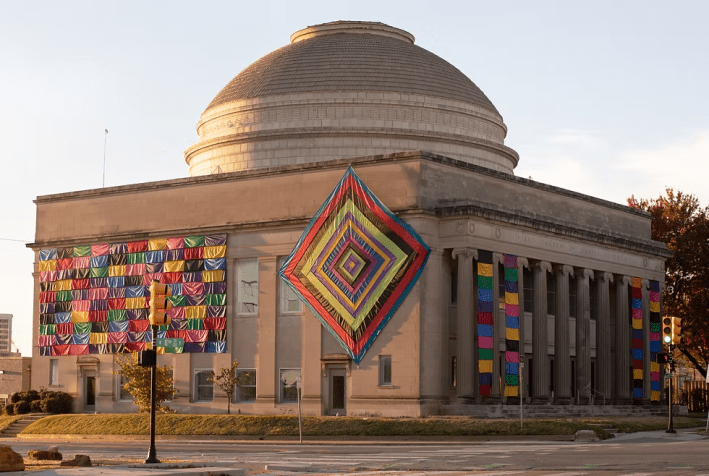

Drive Denver Avenue through this urban liminal space these days and your eyes may catch an unnatural shade of green. It belongs to a temporary art piece that was recently installed at the Plaza of the Americas, an unassuming triangular slice of concrete located between 7th and 8th Streets. For me, this piece sparks more creative thinking about the development of downtown Tulsa and the role of public art in modern city life than any dissertation or discussion possibly could. It’s exactly the type of public artwork Tulsa lacks—and what it needs.

This work—Assembly, by Tulsa Artist Fellowship alum Richard Zimmerman—is the latest installation from the Urban Core Art Project2 and will remain at the plaza until next September. Seen from a moving car, it looks like an array of tree-like towers; what you see at closer range are nineteen vertical sculptures, two others placed in the plaza’s empty planters, and three circular, bright orange benches. Its dominant shapes are somehow both spindly and lumpy. The forms recall narrow nearby cathedral spires, yet they’re filled with the unruly shapes of found objects and sealed with an artificially green durable fiberglass casting material, the same material that doctors use to wrap broken bones.

Visitors can scan a QR code to reveal the sculptures’ innards, which were sourced from Tulsa’s curbsides, vacant lots, and a municipal waste facility. The work’s cast wrapping also evokes playground excess and associated fractures; leaving behind a Sharpie signature or well wishes would be completely appropriate.

Alongside its imagery of fragmentation, one of Assembly’s most compelling qualities is its unlikely cohesion. Though each individual sculpture is unique, they coalesce to quietly acknowledge the park’s existing order—“rather than reinforcing [its] rigidities,” as Zimmerman puts it. At this largely ignored plaza, the sculptures are exaggerated enhancements, but they do not mock the existing city infrastructure. Instead, the design is generous in its consideration of existing elements, echoing those forms and then adding amenities, such as benches, to soften the plaza’s concrete contours.

Americas’ History

A cursory search of the Plaza of the Americas’ backstory reveals very little. Its apparent peak came during a 1991 visit to Tulsa by Venezuela’s then-president, Carlos Andres Perez. Venezuela’s ties with the city began in 1990 when Tulsa-based Citgo Petroleum Corporation became a subsidiary of Petroleos de Venezuela S.A., the state-owned oil company of Venezuela. During this visit, Perez received an honorary degree from TU and, in exchange, granted the city a statue of Simon Bolivar. As a tribute to Latin America’s libertador, the statue exuded George Washington vibes to celebrate Oklahoma and Venezuela’s shared transnational ties of petroleum extraction and state-making. Regrettably, the statue was frequently defaced and by 2006 was moved to Gilcrease Museum. In its absence, the obscure, minimalist concrete plaza that surrounded it persists.

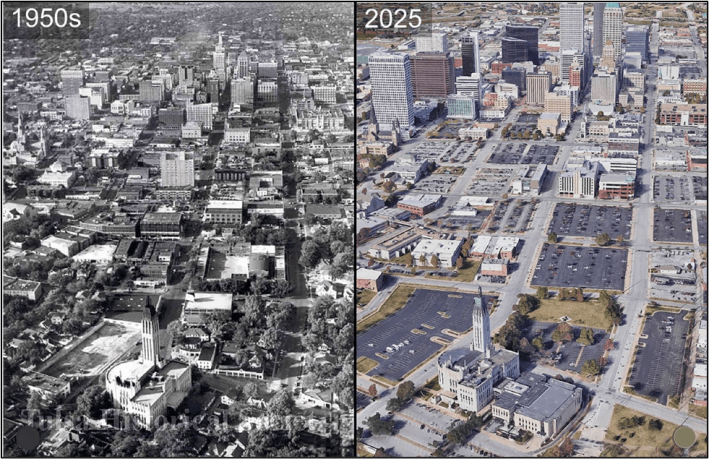

However discouraging, a story like this is a tale as old as time, and hardly unique to Tulsa. Every few decades, city planners champion a new trend to reinvent downtowns and transform tired streetscapes for development. Over a century ago the City Beautiful movement left a legacy of grand boulevards and linear parks between lanes, elaborate medians that now require much mowing. Later, mid-century urban renewal projects would demolish entire neighborhoods for highways and swift transport of cars between downtown and its suburbs, a throttle for white flight for those with means to flee. The 1980s granted downtowns these bizarre “pedestrian malls,” like Tulsa’s Main Street—a particularly strange trend during a decade when no one wanted to be downtown at all, let alone walk there.

A city’s urban design often amounts to a collage of styles that reflect the tastes du jour of past mayors and chambers of commerce. A survey of downtown Tulsa readily reveals this collection of disconnected, dated legacy projects, each selected for a particular moment that only lasted so long.

Maybe I like the Plaza of the Americas because it escaped this logic. Its design suggests little ambition. Sure, there are neat lines, a few trees, limited seating. Otherwise, it’s not trying very hard.

I find this refreshing. City planners and public officials are charged with the impossible task of making downtowns orderly, efficient, and safe. The reality is that cities are messy. Attempts to tame them are often well-intended and just as often foolish. An installation like Zimmerman’s Assembly acknowledges that folly through “comic imagining,” while still leaving its own mark. Freed of the burden of permanent design, a temporary installation can be playful, thoughtful, and welcoming.

Where Does Our Art Belong?

Earlier this year, a new friend disarmed me with this question: “What is the most public form of public art?” I would repeat it often to others in the following months, and the answers ranged widely. My favorite was from a bus driver, totally agnostic about art but highly specific about location. He told me that any art installed inside his bus was the most public form of public art because his passengers would be unable to ignore it. His answer got my own wheels turning round and round.

A lauded public art commission will typically place an artist’s work prominently, somewhere well-designed, well-funded, well-lit, and well-trafficked. In Tulsa that might mean Guthrie Green or the Gathering Place, both exceptional examples of public space and compelling canvases for public art. Still, these places are already destinations. Visitors go there for concerts or other kinds of programming. In such spaces, art can easily exist as an enhancement for a preexisting, prescribed sense of place.

Assembly is worth visiting for many reasons, but I want to focus on its location, largely because I’d prefer to see art enliven similar places that are ordinary. Better yet, I want more art in places that are obligatory. I want to go to the DMV and not feel like I waited that long because there was something interesting to look at while in line. I am maybe most captivated by installations in airport terminals. Regardless of the actual art, I am already held there until my flight boards. The built-in audience for airport-based art may never see the work by choice, but is all the more open to its display.3

Many Tulsans probably drive by Plaza of the Americas daily, oblivious to its existence and the existence of people spending time there. However few its amenities, the plaza is almost always populated, mostly with MetroLink riders waiting for the bus; there are three different routes within as many blocks of the plaza and little seating elsewhere. Others are there without a bus or an agenda. After all, a place that’s rarely noticed is also a good place to be left alone. Plaza of the Americas is perhaps most remarkable for that quality: it’s a place where people, and especially people without stable housing, are allowed to simply exist.

This July, another transit plaza nearby received its own installation. Seemingly overnight, the sidewalk along 4th Street, just south of the Denver Avenue Station, was covered in boulders. Much like Plaza of the Americas, this sidewalk was another de facto dwelling spot for those with few places to go or stay, particularly desirable for the plentiful shade of its mature tree canopy. Now, that shortlist of spaces is even shorter, though some people endure the discomfort and sit there anyway.

These boulders were justified foremost as a public safety measure and simultaneously billed as a forthcoming public art project. I understand that MetroLink and police are charged with ensuring the safety of the station, as well as downtown residents and visitors, especially at the nearby BOK Center. This is a challenging job—one that few critics of this initiative would undertake.

Lurking underneath this issue are questions of public safety: how we define it in order to protect it. Law enforcement agencies rely heavily on crime statistics, but these numbers hardly indicate whether or not people actually feel safe. That perception differs greatly and depends on widely-ranging factors, from the availability of functional streetlights to the public mood, which can swing mightily depending on the sensationalism of the most recent NextDoor post.

However subjective, downtown’s vitality depends on a perception of safety, and policymakers must make tough decisions about whose safety is most at risk, based on what factors, and how to best deploy resources accordingly. Every city confronts these challenges; like all of them, Tulsa has yet to figure it out.

Ultimately, unsheltered homelessness is a lived experience, not a problem with a solution. Even with expanded shelter capacity and permanently supportive housing, the gravitational pull of social services, courts and jails will draw the people who use or are confined to them. Boulders and similar initiatives simply hassle and displace those who can’t afford to drive themselves downtown and pay the meter for a court date.

When we design cities to be perfect, rational, or attractive, we design them to be exclusive. With scarce dollars to go around, any decision to dignify a particular place implies a corollary decision to overlook others. Only so many places qualify for such dignification, and these are the most likely sites for public art.

Locating art in places that are well-funded and well-groomed is like sticking another magnet on the fridge where you’d grab food regardless. Assembly is a rare work that inverts this exclusionary ethos and places art somewhere people need to be, or, at minimum, where they’re allowed to be. The work lends levity and creativity to a plaza with far more activity than amenities, largely devoid of intentionality and investment. In doing so, Assembly acknowledges the disparities within Tulsa’s downtown by dignifying a plaza otherwise viewed from car windows.

Rethinking Art As Luxury

If Assembly seems novel, why is that? Why does our public art so often miss the mark? These questions ring true anywhere, but they seem to hit particularly hard in Tulsa. If limited sales tax dollars barely cover the costs to maintain our roads, then public art is understandably an afterthought, a luxury we simply can’t afford.

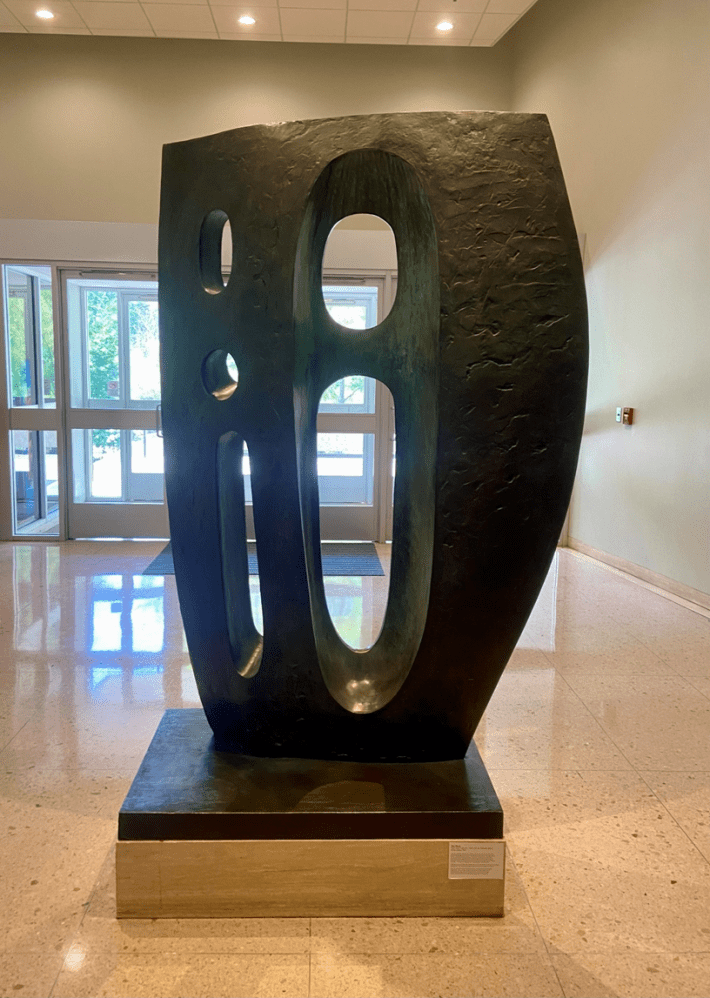

And yet, our own ordinances require it. In the 1960s, Tulsa established one of the nation’s earliest Percent for Art policies, which dedicates one percent of the budget for any new public facility to public art. Though around 400 works of public art exist within the City of Tulsa’s collection, the ability to enjoy it is restricted to attuned observers. An example is Sea Form by modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth, which sits quietly in the promenade of the Tulsa Performing Arts Center. Its visitors are either art insiders, or a different type of insider: PAC guests who know the side bar behind Hepworth’s sculpture typically has a shorter line than the one in the main lobby.

Despite 50-plus years worth of required commissions, Tulsa’s public art collection still seems spare. The Percent for Art budget can be quite generous, but that’s mostly because it’s derived from expensive and infrequent public projects.4

Another reason for the relative anonymity of our public art is its default location next to whatever public project funded it. Even a new wastewater treatment plant is treated with public art, even if it’s only ever viewed by the plant’s employees, who are otherwise preoccupied with treating the rest of Tulsa’s shit.

Our largest, priciest collection is located inside the BOK Center and was valued at $1.35 million when the arena opened in 2008. Still, the art is visible only during events and, even then, on an “If You Know, You Know” basis. The next time you’re in line for a $10 Miller Lite, look down. Odds are good you’re standing on one of four 22-foot terrazzo floor medallions designed by father-and-son Cherokee artists Bill and Demos Glass. That’s not to mention the 24-foot-long painting by Joe Andoe, which hangs further back in the concession area.

Other cities divorce their art funding from these individualized projects, instead opting to pool the combined Percent for Art budgets into a citywide fund. This model affords more opportunities for artists by diversifying where those dollars land. Installations can be permanent or temporary; performances and programming are also eligible. In this model, funding for an affordable ceramics class or upgrades to a park amphitheater used for community concerts are both fair game, pending the priorities of public officials and institutional stakeholders like Tulsa’s appointed Arts Commission. In contrast, our status quo will support a lone public art project whenever we finally build an animal shelter or other crucial facility, effectively limiting our arts opportunities to whatever overall appetite exists for public projects among voters.

All told, there is no consistent, discretionary money for public art or arts programming, at least in the way that the city council budgets for mowing or bulky waste pickup service each year. Beyond these à la carte Percent for Art projects, our only other guaranteed arts funding will expire in 2032.5

And yet, every once in a while, a standalone arts opportunity rides the wave of a major political priority. The much-beloved Cry Baby Hill statue is the most recent example of this type of project. In 2023, Mayor Bynum commissioned a contemporary Route 66 roadside monument to celebrate the Mother Road’s 2026 centennial. The project would draw from long unspent 2006 funding for an untenable Route 66 Museum. Honestly, it was a great idea, up until the moment it became an art contest. At the time, Tulsa was on the cusp of becoming the Capital of Route 66™. Significant fanfare is planned for 2026, including a world-record shattering classic car parade. Mary Beth Babcock’s collection of fiberglass giants was growing—why shouldn’t the City throw down too?

As an art commission, the $250,000 budget, independent of philanthropic involvement, was an astounding amount of money in Tulsa. In hindsight, the whole affair was a pre-destined powder keg. Ensuing controversy pitted local artists against Route 66 boosterism and tourism dollars anticipated as part of the 2026 centennial celebration. Tensions were heightened by the project’s price tag, which was $100,000 more than Vision Arts distributed the same year.6

Beyond such one-offs, public art is often a product of private funding manifested in public spaces. Returning to the apparent rarity of Assembly, such works are often commissioned in tandem with other city-making enterprises: to beautify a newly christened destination, for instance, or to encourage the next emerging “district.” As a person who wants more art, everywhere, for everyone, I try to limit my criticism around these endeavors. Any publicly-funded art project is an anomaly worth celebrating.

Given the limitations of our funding mechanisms for public art, Assembly and the Urban Core Art Project demonstrate a different model. UCAP funds projects with private dollars, but the artist is enabled to make executive decisions. Additionally, UCAP exclusively funds temporary projects, a need identified by veteran Arts Commission members who have witnessed the limited reach of public art as it’s practiced in Tulsa. Without obligatory ties to a specific permanent project, these art opportunities are less restricted by design trends du jour, or shackled to sites with limited visibility, like fire stations or maintenance facilities.

Lastly, major permanent public sculptures are not only expensive and exclusive, they are also long-term liabilities for cities. Amidst competing priorities, they’re rarely maintained as intended, in part because they require specialized upkeep. Temporary public art is less intensive for cities to maintain, and creates more jobs for artists, while disarming the public reaction we’ve seen to permanent installations. With more arts initiatives overall, emerging artists would be more likely to receive commissions and otherwise overlooked places like Plaza of the Americas would become more likely candidates for a roaming, roving catalog of creative installations.

Assembly and other like-minded temporary installations loosen the confines and expenses of permanent public art to make space for curiosity, diversity, and exploration. Cities are messy; art like this, with its ephemerality and specificity, responds to and honors that messiness. Even when art seems ancillary to public life, this type of work feeds the irrational yet necessary impulse to seek ongoing improvement in public spaces. As James Baldwin reminds us:

Nothing is fixed, forever, forever, forever,

it is not fixed;

the earth is always shifting,

the light is always changing,

the sea does not cease to grind down rock.

Generations do not cease to be born,

and we are responsible to them

because we are the only witnesses they have.

Footnotes

Footnotes

- For further visual evidence, the University of Oklahoma College of Architecture has a helpful interactive map here.Return to content at reference 1↩

- Full disclosure: I’m on UCAP’s board.Return to content at reference 2↩

- The next time you go through security at Tulsa International Airport, you can pass a few minutes by looking upward at Shane Darwent’s “Sunrising,” a 34-piece hanging art installation that rotates on a timer.Return to content at reference 3↩

- For example, our newest fire station, Station 33, was dedicated in 2022 with accompanying public art. The second youngest is Station 16, dedicated 13 years earlier in 2009. The projects that trigger art requirements are few and far between. Particularly in a low-tax state like Oklahoma, such buildings are usually funded begrudgingly at the ballot box, where the limited voting populace agrees on little besides the necessity of essential public services. If prevailing wisdom concludes that we can’t have nice things, it’s because we don’t want to pay for them. Return to content at reference 4↩

- If that sounds confusing, it is. Stay with me. In 2016, voters approved the Vision Tulsa funding package, an $884.1 million cornucopia of public projects. Some of those, like Zink Dam or airport upgrades, were initiated soon-ish thereafter; others are divvied out as a much-slower IV drip. The $2.25 million Vision Arts initiative falls into the latter bucket and will provide $150,000 annually for the next seven years to arts programs that boost economic development. This year, funding will support the Red Dirt Relief Fund’s Skinnerfest, Bruce Goff celebrations, and sorely needed Tulsa Opera programming, and the program has provided $1.35 million in arts funding since 2016. Still, these are selected as much for their likelihood to create tax revenue as for the artistry on display, and the program’s days are ultimately numbered unless extended through a similar vote. Return to content at reference 5↩

- Regardless of where the Cry Baby goes (or whether or not it’s even eventually installed), its unfortunate legacy rests with future municipal leaders that will surely hesitate to embrace arts funding, amidst other concerns affording greater political capital and continued electability. Even when Chicago commissioned a 50-foot untitled sculpture by Pablo Picasso in 1963, the work was so unpopular that the city’s legendary big boss mayor, Richard J. Daley, would qualify his support at its unveiling by stating, “We dedicate this celebrated work this morning with the belief that what is strange to us today, will be familiar to us tomorrow.”Return to content at reference 6↩