Working at a bookstore that specializes in rare archives, books and ephemera, I often have the privilege of handling lesser-known and obscure history: people, places or moments in time that have been long forgotten.

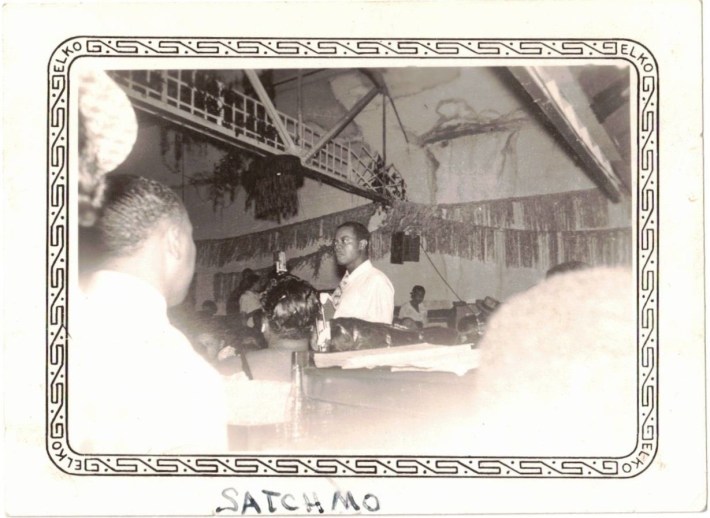

Recently, while excavating a source in pursuit of local history, I stumbled on a collection of photos taken inside a jazz club on Greenwood Ave in the 1940s. One of the photos was of Louis Armstrong.

Twenty years before knocking The Beatles out of the number one Billboard spot in 1964 with “Hello Dolly,” there Armstrong was, in Tulsa, in a jazz club I’d never heard of.

I immediately went into internet sleuth mode and found … nothing. No information about this place existed online, apart from a couple of auction reports for photos and a random tour schedule that featured the club as a stop for Tiny Bradshaw and Lil Green in 1941. I reached out to Tulsa historians and experts in the field of Oklahoma music to no avail.

Now, it’s not uncommon to learn of Oklahoma’s more interesting, underground or despicable past outside of schoolbooks. I remember wondering why I learned about the 1921 Race Massacre in my 20s, as opposed to in school. Why didn’t more people know about Larry Clark and his deeply unsettling book, Tulsa, or the poets Ron Padgett, Joe Brainard, Ted Berrigan and their ties to The Beat Generation? Not to mention one of the best crime writers of the 20th century, Jim Thompson from Anadarko, OK, and his influence on Stephen King?

Here again, Oklahoma’s history presented a historical mystery. What was this club and how long was it open? And why hadn’t I heard of it?

* * *

When asked to name historic music venues in Oklahoma, you’d be hard pressed to find anyone in Tulsa that doesn’t mention Cain’s Ballroom. In its nearly 100-year history as a dancehall, Cain’s has hosted some of the most influential performers in American music, from Hank Williams and Wanda Jackson to the Ramones and Muddy Waters, Bob Dylan, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and of course, Bob Wills.

But just as the King of Western Swing was ending his tenure at the historic dancehall,1 another notable ballroom was about to make its debut on the Tulsa music scene. And although this new club showcased some of the most groundbreaking and influential artists in American music, it tragically went up in flames before disappearing from the public memory.

At the beginning of the 1930s, jazz was in a state of becoming. The hot jazz of the Roaring ‘20s launched the careers of Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton, and Duke Ellington in time to see the repeal of Prohibition before swinging its way into a new decade. Along with Armstrong and Ellington, newcomers like Billie Holiday, Benny Goodman, and Ella Fitzgerald were about to receive national recognition.

In Chicago, a former sax player turned insurance salesman established a jazz magazine named after the first beat in a musical measure: DownBeat. By the late ‘30s into the early ‘40s, DownBeat Magazine boasted some 80,000 subscribers and, in Tulsa, OK, two employees at the rebuilt Dreamland Theatre in the Greenwood District were clearly tuned in to the new publication.

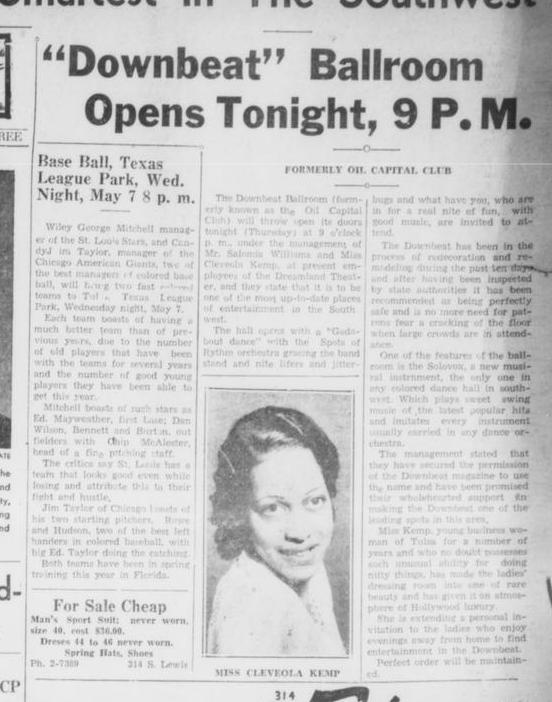

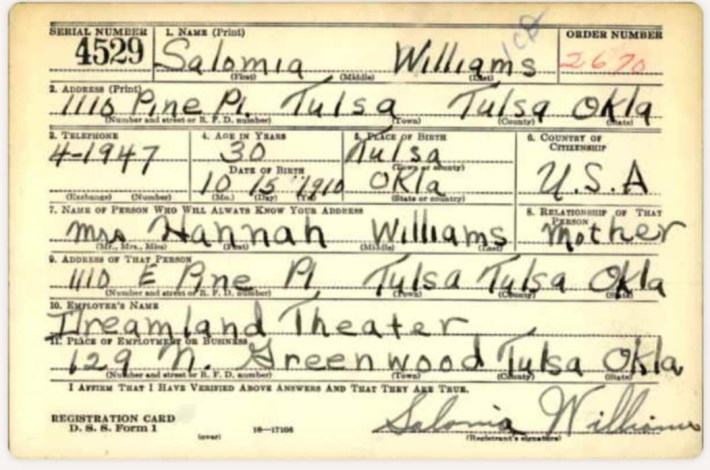

On May 3, 1941, 30-year-old Salomia Williams (house manager of Dreamland) and 30-year-old Cleveola Kemp (Dreamland’s secretary) opened a new “sepia” ballroom called Down Beat,2 located above the Dixie Theater at 120 ½ N. Greenwood (formerly the Oil Capital Club), just across the street from Dreamland. Salomia and Cleveola (nicknamed Spunk and Punk) advertised that the new venue “is to be one of the most up-to-date places of entertainment in the Southwest.”3

The Down Beat Ballroom boasted a rare Solovox, a monophonic electric keyboard and early precursor to the synthesizer; according to the May 3, 1941 edition of the Oklahoma Eagle, it was “the only one in any colored dancehall in southwest.” In addition, the Eagle stated that “Miss Kemp … has made the ladies’ dressing room into one of rare beauty and has given it an atmosphere of Hollywood luxury.” Guests were assured that “perfect order would be maintained.”

Within the month, Spunk and Punk secured performances with Lil Green (one of the leading blues and R&B singer-songwriters of the ‘40s) and Tiny Bradshaw, as well as Tulsa’s own Ernie Fields, who went on to have a Billboard #4 hit with his rendition of Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood.”4 Fields and his Orchestra became a mainstay at the Down Beat, playing frequently throughout the next couple of years.

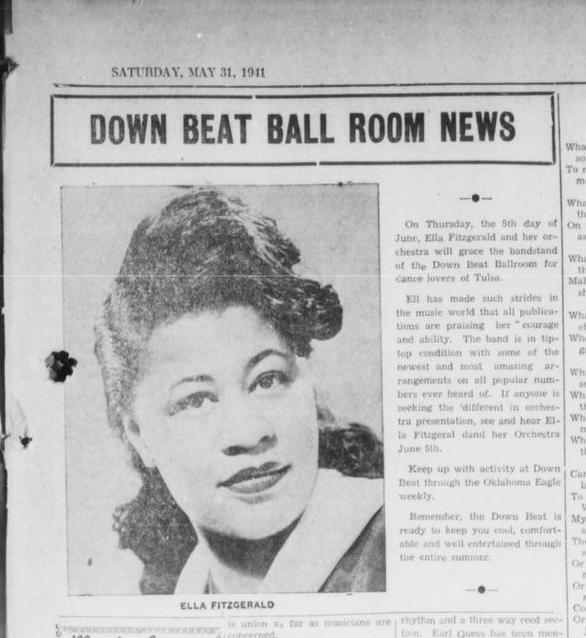

The “First Lady of Song,” Ella Fitzgerald, graced the bandstand of the little club above the Dixie on June 5, 1941,5 almost 20 years before receiving her first of 14 Grammys and selling over 40 million records. Open just over a month, Spunk and Punk’s establishment had already showcased one of the most popular and influential female vocalists of the 20th century.

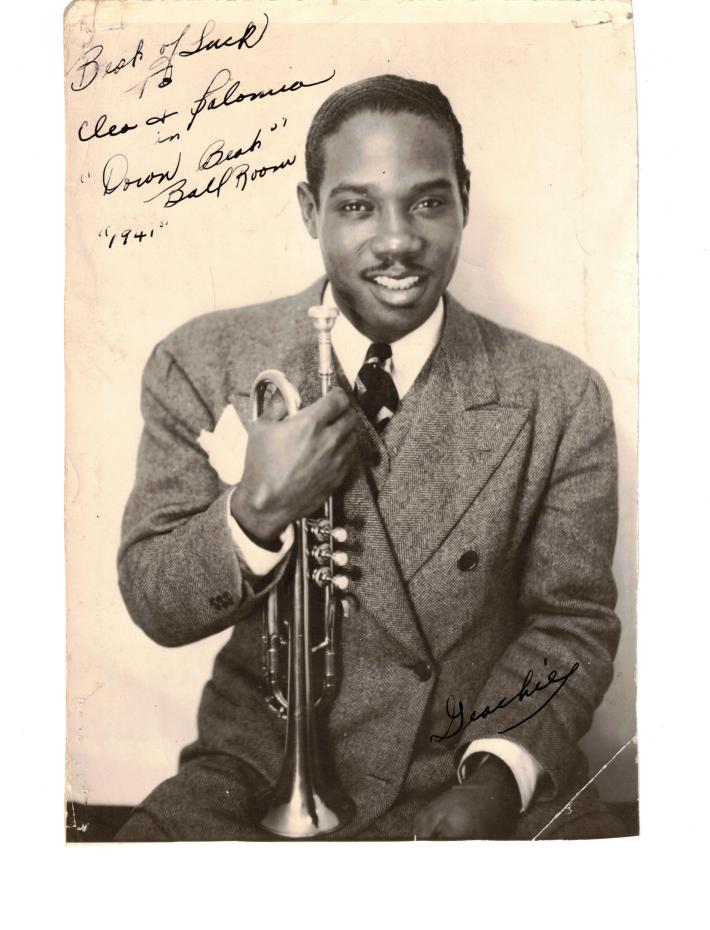

The house band, The Spots of Rhythm Orchestra, also boasted a phenomenal lineup, featuring Eddie Nicholson, formerly of the Charlie Christian unit, and Hal “Cornbread” Singer, who would go on to play tenor sax on Wynonie Harris’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight” in 1948 and write his own early rock ‘n roll tune, “Rock Around the Clock,” in 1950, four years before Bill Haley released his song of the same title. The Orchestra also included Vernon “Geechie” Smith and members from Lionel Hampton’s and Ernie Fields’ bands, ensuring that the Down Beat Ballroom was on track to becoming one of the hottest jazz clubs in the South.

Soon, famed big band leader Woody Herman agreed to “play ofay6 band for colored,”7 breaking color barriers by playing for a black audience. Then, “just about ten minutes after the Oklahoma Eagle hit the street … with glaring headlines and announcements about the Woody Herman Orchestra,” Herman’s manager canceled, saying the venue was “too far south.” Although Spunk and Punk were clearly skeptical, they didn’t let this speed bump slow them down.

The Down Beat soon booked Earl “Fatha” Hines, one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano. Ernie Fields’ Orchestra played five more times in the next five months including Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve.

1942 would prove to be a pinnacle year. In addition to performances from Ernie Fields and the newly solo Vernon “Geechie” Smith, the Down Beat hosted several events in 1942, including the OK Teachers meet, the Sans Souci Club, and “Junior Jumps” where kids were welcome and no alcohol was served. The Down Beat also donated to the North Tulsa U.S.O. Club.

June saw the club hosting the Original Carolina Cotton Pickers, a territory band first created in the 1920s from the Jenkins Orphanage, performing on the bandstand. Then, on August 19th, years before “Hello Dolly!” and “What a Wonderful World” hit the airwaves, the Down Beat showcased Louis Armstrong to the delight of what was likely a sold out crowd.

The next couple of months saw “The 20th Century Gabriel,” Erskine Hawkins, on stage; his iconic song “Tuxedo Junction” was a Billboard No. 1 hit for Glenn Miller and His Orchestra just two years earlier. Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy played the Down Beat one month before his chart topping hit “Take It and Git” became the first No. 1 on Billboard’s Harlem Hit Parade, a precursor to their R&B chart.

In October, Benny Carter, bandleader for “the first interracial and multinational band” and a saxophonist who Louis Armstrong referred to as “The King,” stepped onto the Down Beat Ballroom bandstand. This was one of the last few performances for Carter before he moved to California to become one of the first African Americans to produce soundtracks for film and TV. While Dizzy Gillespie toured in Benny Carter’s Orchestra in 1942, whether he played at this performance is unknown.

In 1942, Spunk was drafted.8 By this time Punk, now his wife, was assistant manager of the Dreamland Theatre,9 and took over sole managerial duties at the ballroom. She kept the Down Beat running and maintained a notable roster for 1943, with such greats as Earl Hines, Louis Jordan, Buddy Johnson, and local legend Jay McShann, but the Down Beat hosted fewer performers and events, never fully reaching the peaks it hit in ’41 and ’42.

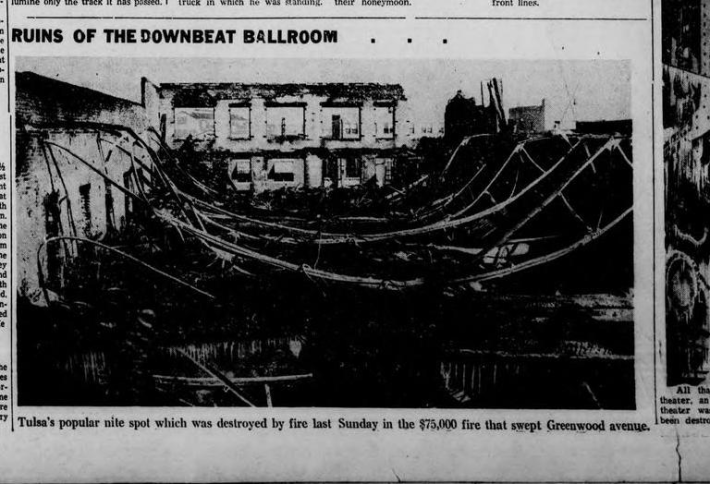

On Sunday, January 15, 1944, Greenwood residents woke to find that a “fire of unknown origin” had destroyed the Dixie Theater, damaging several nearby businesses and causing an estimated $75,000 in destruction before firefighters were able to get the blaze under control.10 Firemen struggled with the ice and the cold before the roof of the Dixie collapsed, taking the Down Beat Ballroom with it.

Presumably, the fire started in the rear of the Dixie Theater, which had been vacant for years. Bijou Amusement co., which owned the Dixie, Dreamland, and Rex theaters, had no apparent intention of reopening the Dixie after purchasing it; the theater had been vacant for some time. According to the January 15, 1944 edition of the Oklahoma Eagle, “One theory of the origin of the fire is that it was started by hoboes and transients … to seek shelter from the blizzard, built a fire in a bucket and then left without extinguishing it. Another is that it may have been caused by defective wiring.”11

Although the Down Beat was in operation for just under three years, its significance to the history of Tulsa’s music scene cannot be overstated. While Cain’s Ballroom remains standing as the house that Bob built, the Down Beat Ballroom shares the distinction of showcasing some of the most influential musicians in the nation’s history and is worthy of recognition as the house that Punk and Spunk built.

Footnotes

- San Antonio Rose, Charles Townsend.Return to content at reference 1↩

- DownBeat Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 13.Return to content at reference 2↩

- The Oklahoma Eagle (Tulsa, Okla.), Vol. 24, No. 39, Ed. 1 Saturday, May 3, 1941.Return to content at reference 3↩

- The Oklahoma Eagle (Tulsa, Okla.), Vol. 24, No. 41, Ed. 1 Saturday, May 17, 1941.Return to content at reference 4↩

- DownBeat Magazine Vol. 8, No. 13.Return to content at reference 5↩

- Old slang for a white person.Return to content at reference 6↩

- The Oklahoma Eagle (Tulsa, Okla.), Vol. 24, No. 48, Ed. 1 Saturday, July 5, 1941.Return to content at reference 7↩

- U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946.Return to content at reference 8↩

- The Oklahoma Eagle (Tulsa, Okla.), Vol. 33, No. 30, Ed. 1 Saturday, April 3, 1943.Return to content at reference 9↩

- The Oklahoma Eagle (Tulsa, Okla.), Vol. 23, No. 24, Ed. 1 Saturday, January 15, 1944.Return to content at reference 10↩

- The Oklahoma Eagle (Tulsa, Okla.), Vol. 23, No. 24, Ed. 1 Saturday, January 15, 1944.Return to content at reference 11↩