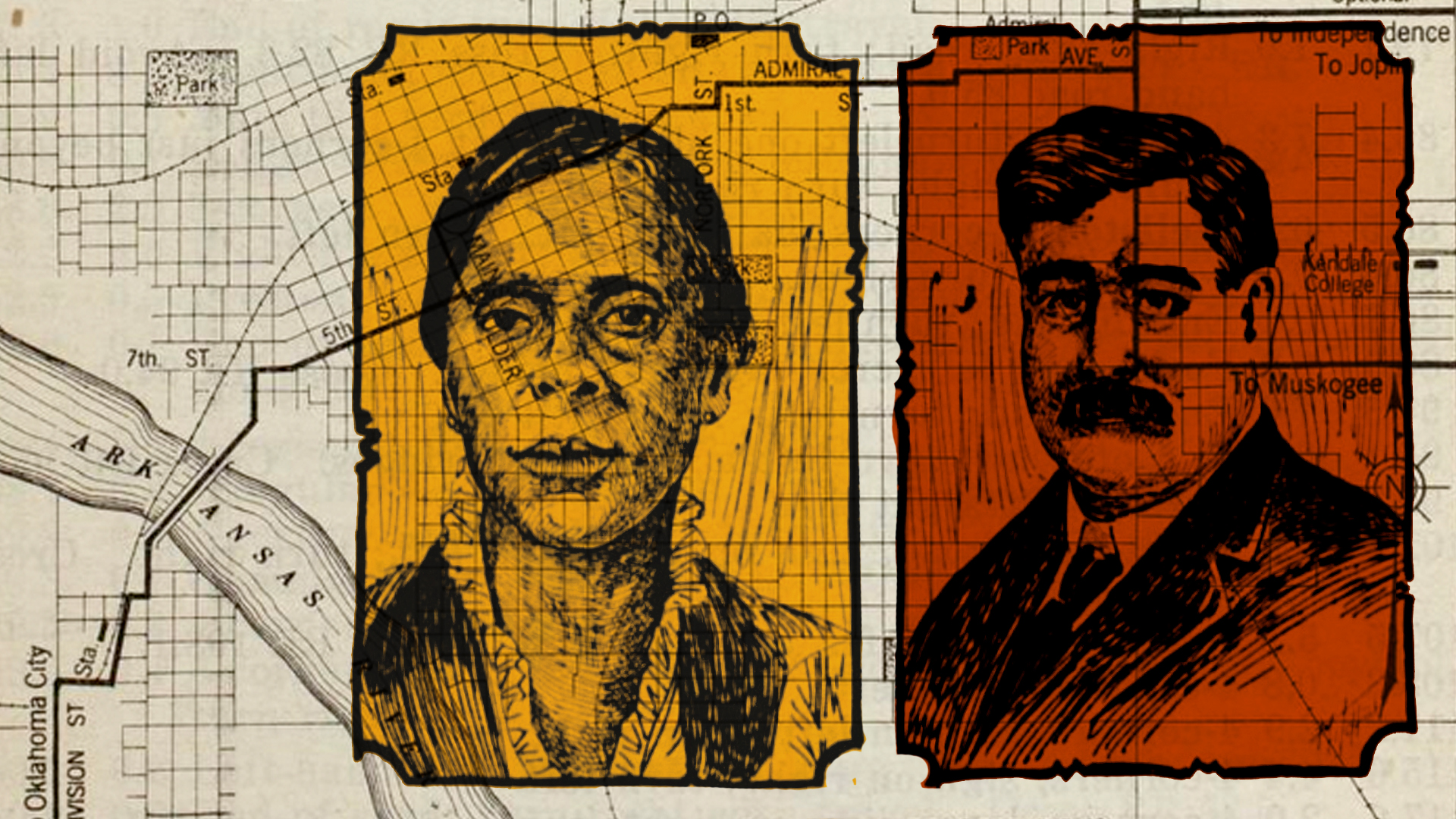

Sadie James said she could make a man swear hell was an icebox. James was a local celebrity, but much of what she said was deemed “unfit for print” in Tulsa newspapers. She had been married “six or seven times”—her estimate—and sold bootlegged whiskey to the oilmen of the Magic City. In the 1910s, she went on to expose an elaborate fraud committed by a wealthy philanthropist before vanishing from history.1

A century ago, everyone in Tulsa knew about Sadie James and her saloon, the Bucket of Blood.

But where was it? And how did the child of an enslaved woman, raised in a Kansas brothel, become the most feared and respected woman in Tulsa at a time of red-hot racial hatred?

I went downtown looking for answers, starting with a home address she provided in a courtroom testimony: 504 E. Archer St. You might recognize that as the current location of the U-Haul Building, but it was built as the headquarters of the National Supply Company in 1925. There are several plaques on the building. The most prominent reads:

The famous American songwriter Bob Wills immortalized this location with the lyrics:

Would I like to go to Tulsa, you bet your boots I would.

Just let me off at Archer, and I'll walk down to Greenwood.

Take me back to Tulsa, I'm too young to marry.

If you were too young to marry in early 20th-century Tulsa, you might have, at one point or another, found yourself acquainted with Sadie James. She lived on Archer, but her business was somewhere north of Deep Greenwood, just outside the city limits. She estimated that 150 to 200 customers came into the Bucket of Blood each night. Some of the characters started trouble, so Sadie packed a pistol on each hip.2

A prominent Oklahoma attorney accused the saloon of being a brothel, which irritated Sadie. “It was a roadhouse, Judge,” she told him in 1917. “There was one living room and the rest was a gambling house where we sold beer and danced.” In an entirely segregated city, Sadie’s place was one of the few businesses that catered to all races and creeds. Whereas other managers had struggled to maintain the peace when card games got heated, Sadie kept things cool for the most part. She covered the walls with thousands of playing cards as part of the decor.3

I looked in vain in city directories for the exact location of the roadhouse. Sadie described it as located on Greenwood Avenue on the northern route out of town. I found a clue in a clipping about an outlaw named Catfish Dickson, who holed up in Sadie’s place after robbing banks.

Police described a chase that happened where the Midland Valley Railway almost intersected with Greenwood. The tracks are long gone, but the Osage Valley Trail follows the old railroad. The trailhead is near the 900 block of Greenwood, where the city would have ended in the 1910s. Another Tulsa World article described the Bucket of Blood as being north of the intersection of the Santa Fe and Midland Valley Railroads. The railyard a little further south and east is still there. On the other side of the street is a parking lot and a small rise before you come to OSU-Tulsa.4 According to a 1920 map, the city ended right around there.

My best guess is that this unassuming OSU-Tulsa parking lot was the site of Tulsa’s most infamous saloon, which was destroyed in 1921. Shady oil deals, high stakes poker games, a jazz pianist who doubled as a bouncer, a pistol-packing Cherokee Black woman, white bootleggers—this slice of Tulsa had been its own boardwalk empire.

Up From Slavery, Down From Kansas

When you start looking for Sadie James, the entire world of early Tulsa emerges.

Sadie’s mother, Carrie Bell Ross, fled the Cherokee slaveholder Lewis Ross’s plantation near Salina, Kansas, during the Civil War and gave birth to her only daughter in Chetopa in 1869. Mother and daughter sought to be recognized as Freedmen when the Dawes Commission came to Indian Territory in the last years of the 19th century, but the Cherokee Nation rejected Carrie’s application.

With no land forthcoming, Carrie Ross started street preaching for a group she called the “Loyal Ethiopians and Royal Cherokees” in Greenwood. The group believed Oklahoma was a sham and that God’s wrath would fall upon the white men who ruled the state.5

Carrie and Sadie had a public falling out. Sadie wanted nothing to do with her mother’s sermonizing, and started a hotel in Greenwood, renting a building owned by the entrepreneur O. W. Gurley in 1912 or 1913.

Gurley was a wealthy Black man from Arkansas who saw Tulsa as a land of opportunity. He had purchased 320 acres just north of downtown to establish a Black-run, Black-owned city within a city. Police claimed the Gurley Hotel furnished illegal liquor, and hit him with a charge that was later dismissed in court.6 Gurley’s wife Emma was furious, as she was the real businesswoman behind the hotel. Emma Gurley had harsh words for any customers demanding “women of pleasure” or liquor from her establishment. She evicted Sadie, who found another job managing Tulsa’s most popular—and infamous—roadhouse, the Bucket of Blood.

The owner of the saloon was a shady white man named Charles McClelland, who would disappear once hit with criminal liquor trafficking charges in 1913. It was a one-storey wood building on the allotment of a Cherokee citizen named Looney Price. Before Sadie took over management, there had been gunfights and holdups. The previous manager, Tobe Thompson, had shoved a .45 pistol into the gut of a Tulsa police officer during one altercation. Sadie did her best to impose order, and she managed to stop a county judge from issuing a permanent injunction on the Bucket.

Sadie consistently denied charges of running a brothel but she did admit to being a retail seller of bootlegged whiskey in a dry town. Her supplier was “the King of the Oklahoma Bootleggers,” Bill Creekmore.7

Creekmore offered protection at the highest levels of city and state government and openly bragged about dodging the law and buying off politicians. From his wholesale distribution shop in Joplin he sent packages to fictitious people, who adopted aliases and retailed the booze across Oklahoma. Creekmore was not some hick in a holler. He was, in the words of the Tulsa World, “the biggest asset the Democratic Party has in this state.” He was also a business associate of Charles Page, who would eventually become entangled with Sadie James in more ways than one.

To be a Black woman hotelier, saloon keeper, and all-around fixer in early Tulsa, Sadie needed to have some heavies around. Some became her boyfriends. One such person was Walter Agnew. Agnew wanted to marry Sadie, but she eyed him with suspicion at her house. One day, she caught him pilfering a drawer in her bedroom, looking for cash or jewelry.

That was it, she said. She wanted Walter out. She told him to stay away from her saloon as well. One night, after closing, Sadie heard someone trying to break in through the roadhouse’s back door. She warned the intruder: break down the door and she would blast him. He continued until he found his way in. Sadie aimed her pistols and felled the man with a shot through the stomach. Walter Agnew was dead.

The Tulsa Democrat called her a “murderess.” When Sadie—then known as Sadie Johnson—was acquitted of murder, the Democrat called for the entire panel of jurors to be discharged. She later acquired the nickname of “The Notorious Negress Sadie James.” Her self-defense was, in the eyes of the white Tulsa establishment, a “miscarriage of justice.” Greenwood itself was in “an intolerable state of affairs.”8 The Democrat—later rebranded as the Tribune—would continue its race-baiting sensationalism until a full-scale invasion of Greenwood took place in 1921.

Around the same time, a patron of the Bucket of Blood solicited an 18-year-old woman for sex. The woman—likely Sadie’s daughter, Eva—sliced the man through the abdomen with a razor, nearly killing him. This, Sadie emphasized, was not a brothel. And although she hated the name “Bucket of Blood,” the saloon had now earned its nickname.

Daddy Page Meets Sadie

The Bucket of Blood was a crossroads for more than just liquor and dancing. Sadie’s role as proprietor gave her access to information, too. She later told a federal judge that virtually everyone involved in buying Indian oil leases was operating outside the law. “I know they are crooks,” she said. Indeed, Tulsa County District Judge Gubser, who considered the injunction against the Bucket, was later exposed for taking bribes from Charles Page.9

The crooks, as it turned out, needed Sadie more than she needed them.

Among Sadie’s customers was the philanthropist Page, who was building a reputation as the state’s most generous man by the mid-1910s. Page gave all of his profits to the Sand Springs Home for Widows and Orphans, which attracted media attention around the country. He was known as “Daddy Page,” and many people believed he adopted hundreds of the children. (In fact, he never adopted a single one.)10

Page was not the richest oilman in the state, but he had a novel business model: move oil profits to his charity, which then invested in all sorts of infrastructure and building projects in Tulsa. The railway connecting Sand Springs to downtown Tulsa was owned by the Sand Springs Home. The Home owned the largest bottling plant for drinkable water. It owned buildings downtown, and it aimed to control Tulsa’s electrical grid and new water supply.

The Home housed and fed widows and orphans, but it was also a philanthrocapitalist enterprise that had overextended itself. Page had built much, but to pay for it all, he needed help from someone like Sadie to secure a dubious oil lease.

Page had many oil properties in northeastern Oklahoma, but the most valuable oil wells were located on an allotment to a Creek boy named Tommy Atkins. Tens of thousands of barrels of oil flowed out of Tommy’s land each day, but the legal status of the land was in disarray. The name on the oil lease—Tommy’s mother, Minnie Atkins—turned out to be a forgery. Three women claimed to be the boy’s mother. A Black man in Kansas said he was the actual Tommy. And the Muscogee Nation said it was all a big mixup on the Dawes Rolls, that there was no Tommy at all. Page thought otherwise. If he could get Minnie to swear in court that Tommy was her son, he could pay her out and control the oil wealth.11

The problem was: no one knew where Minnie was or if she was even alive. Sadie had known Minnie at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in the 1880s. Sadie convinced Page to pay her $3,000 (a sum worth around $60,000 today) if she could find Minnie and bring her back to Oklahoma.

Sadie said goodbye to the Bucket of Blood and toured the country looking for Minnie, going first from Tulsa to Leavenworth. She spent some time hiding in a little Colorado town called Rye because she feared she was going to be killed by agents of rival oilmen.12 At Fort Lawton in Seattle, Sadie found Minnie Atkins in 1914.

But Minnie had a surprise. “Thomas Atkins was my father,” she told Sadie. Minnie never had a child named Tommy, and the whole fortune now gushing from his land was built on a spurious claim Minnie now wanted to disavow. This news did not stop Charles Page. He viewed the existence of Tommy the way Voltaire considered God: if he did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.

Page ordered his secretary to create fake documents that showed Minnie Atkins as the mother of Tommy. He pressured Minnie to lie on a sworn affidavit. Minnie came to the point of a nervous breakdown. Federal agents—including the Attorney General of the United States—smelled a rat. They sent a spy to record secret conversations with her, in which she said that “they were all crooks at Tulsa. They made [me] lie and swear to lies.”13

Along with the National Attorney of the Muscogee Nation, the Department of Justice investigated Page and found an elaborate scheme cooked up by the oilman and associates to fabricate a boy named Tommy. Minnie died under mysterious circumstances in 1919, while litigation was still pending.

A U.S. probate attorney named Frank Montgomery caught up with Sadie James, who had been a linchpin in the entire scheme. Montgomery gave Sadie a chance to come clean. If she would tell the whole story, she would be granted immunity from several felony charges.

Sadie did not disappoint. She spilled the tea on Charles Page, showing how he used bribery and threats to get his way. She also provided details about a nighttime affair the two carried on at 504 E. Archer St. At one point, Page gave James $50 (around $1,000 today) for sex.

“You never seen a colored woman get so much money out of a white man,” Sadie told a stunned courtroom in 1917.

Sadie scandalized Tulsa. The Tulsa World hinted at the salaciousness with an article about “clandestine visits to a dark office,” but it also noted that much of what Sadie said “was not fit for print.”

A U.S. Attorney asked if Page was familiar with Sadie’s reputation. “He knew how notorious I was,” she replied. “You are pulling this out of me; I certainly hate it, though.”

The Tulsa Morning Times, owned by Charles Page, retorted that it was all “a malicious lie” and Page would be justified in responding to the World’s innuendo “with a shotgun.”14

Sadie's testimony, however, was unimpeachable. She was cross-examined again and again by Page’s lawyers, who tried to get her to contradict herself. They could not break her. She got her immunity, but Page prevailed in his case and continued to fund the Home with the oil money derived from the Tommy Atkins lease through 1922.

The Afterlife of the Notorious Sadie James

Then came the destruction. Sadie’s house was directly across the street from 505 E. Archer, the home of “Diamond Dick” Rowland, a prime target in the Tulsa Race Massacre. Her house and her business were burned to the ground, along with 35 square blocks of Black Tulsa. Sadie’s disclosure about Page’s corrupt practices and the complicity of banks like Exchange National and Tulsa County judges in a massive fraud may have made her a target. She had been demonized by the Tulsa Democrat and Tulsa Tribune, even though she was a fixer rather than a schemer for what the Indian Rights Association called “an orgy of graft and exploitation” of Creek allottees.15

After the massacre, Sadie rebuilt a rooming house at 318 N. Greenwood, where her daughter eventually took over as manager. This new place had only a few whiffs of scandal, mainly revolving around Tulsa’s worst-kept secret: that hotels were retailers for bootlegged whiskey. Booze also flowed freely at the Hotel Tulsa and the Mayo Hotel, but those places served the city’s elite. Mainly, Sadie’s rooming house quietly served as a place for African Americans to live while seeking jobs in the Oil Capital. For decades, mother and daughter participated in the rebirth of Greenwood.

Sadie died in 1955, shortly before a second tragedy—this one packaged as “urban renewal”—was designed to finally destroy Greenwood. Sadie and Eva’s rooming house stood in the path of “progress,” otherwise known as the construction of the Inner Dispersal Loop, which sounded the death knell of a vibrant Black community.

Mabel Little, who lived nearby, had lost her house and business in 1921 and then rebuilt. In 1970, Little told the Tulsa Tribune: “You destroyed everything we had. I was here, and the people are suffering more now than they did then.” The Mabel B. Little Heritage House at 322 Greenwood, next to the Greenwood Cultural Center, was dedicated to her in 1986 in honor of her work to preserve the district.

***

I ended my quest in the parking lot across from the Greenwood Cultural Center, looking at the Black Wall Street mural on the IDL overpass. There are iconic references to Greenwood here: the GAP Band, the Booker T. Washington Hornet, the Dreamland Theater. But missing from the mural is any reference to what else once stood in that location: the last business of Sadie James.

A little more than a century after she roiled the white Tulsa establishment by telling the unvarnished truth, the legend of Sadie James had been forgotten. Almost.

After days of sleuthing, trying to find Sadie’s place, I stopped in at The Tavern and propped my elbows on the bar with my friend Apollonia Piña. I told a bartender a brief version of the story of Sadie and her roadhouse. While he listened, we conjured up a drink of amaro, bourbon, and blood orange bitters. He slid the drink to me. We called it the Bucket of Blood cocktail.

Recipe for the Bucket of Blood Cocktail

1.5 ounce bourbon

1 ounce Cynar (can substitute other herbaceous Italian liquor)

1 spritz of blood orange bitters

Pour over ice and stir gently.

Read more about this chapter in Tulsa history in Russell Cobb's book Ghosts of Crook County (Boston: Beacon Press, 2024).

Footnotes

- The testimony of Sadie James is held in four volumes at the National Archives as part of a record of the trial, U.S. vs. Minnie Atkins, et. al., Equity 2131, Eastern District Court of Oklahoma. Reporters at the time (1915 to 1922) called it the most exhaustive and expensive trial in the short history of the state. It may still hold that distinction. There are over 8,000 pages of documents associated with this case. Return to content at reference 1↩

- “Show Creekmore Was Page’s Pal,” Tulsa World, May 16, 1917.Return to content at reference 2↩

- “Bucket of Blood an Easy Victim,” Tulsa World, October 20, 1912. Return to content at reference 3↩

- “Rice Tells Story of Rowe Shooting,” Tulsa World, May 28, 1914. An interesting side note to this story is that the Tulsa Police officer pursuing the murderer was Barney Cleaver, Tulsa's first Black lawman. Cleaver tried to quell the white mob who invaded Greenwood in 1921. Return to content at reference 4↩

- “Texas Is Hell and Arkansaw [sic] her Wayside Station,” Tulsa Post, July 31, 1911. Return to content at reference 5↩

- “But Gurley Didn’t Own My Building,” Tulsa World, February 24, 1911, p. 5.Return to content at reference 6↩

- “Show Creekmore…” (See #2)Return to content at reference 7↩

- “Summary Discharge of Panels Demanded After Acquittals of Negros Charged with Murder,” Tulsa Democrat, July 15, 1913. Return to content at reference 8↩

- For the complete story of Page’s relationship with Tulsa and Creek County judges, refer to the author’s book, Ghosts of Crook County. Return to content at reference 9↩

- There were several lawsuits brought by people who claimed they were adopted by Page and then cheated out of his estate. In each lawsuit the trustees of the Sand Springs Home argued successfully that no legal adoption was ever carried out, even in the case of Willy Page, who was raised as Charles’ son. Return to content at reference 10↩

- A much more extensive version of this scheme is detailed in the author’s book, Ghosts of Crook County. Return to content at reference 11↩

- Numerous Muscogee allottees in the Tulsa area disappeared or died under suspicious circumstances during these years. See the author’s book, Ghosts of Crook County, for more on Creek murders during the Oil Capital boom years.Return to content at reference 12↩

- This is all part of the massive court record in U.S. v. Atkins, Equity 2131.Return to content at reference 13↩

- “The World’s Blackmailers at Work,” Tulsa Morning Times, June 11, 1917, p. 1.Return to content at reference 14↩

- Zitkala-S̈a (1876-1938), Oklahoma's Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes, Legalized Robbery: A Report. II.127. 1924.Return to content at reference 15↩