We’re on sale! New subscribers get 40% off from Black Friday to Cyber Monday. At The Pickup we write stories for real people, not AI scrapers or search engines. Become a paying subscriber today to read all of our articles, get bonus newsletters and more.

My home state is quite flat. It boggles my mind that I can’t find a single folksy quote to serve here as testament to Oklahoma’s flatness, attributable to some author, poet, or cowboy. I even rooted around for one from one of our equally-flat neighbor states, expecting something like, “The best thing about Oklahoma is, you can see Texas from just about wherever you’re standing,” perhaps courtesy of some mischievous Houstonian writer from the early 1900s with a breezy Wikipedia page.

We can workshop the quote. The point is, Oklahoma is remarkably flat, and when people ask me what growing up in Oklahoma was like, I start with “flat” before launching into the conservatism or recent attempts to ban pornography, because the flatness is the first thing I reliably appreciate about it when stepping out at Will Rogers “International” Airport. The sky, unchallenged by topography or tall buildings, rules tyrant over the Great Plains, banishes the horizon; true, blue infinity. The feeling this induces is a body liberated from friction. It lasts but for a moment, before your eyes get used to it, before you encounter your first of many overpasses and attendant raccoon corpses, and remember to be bored.

But that first hit of blue in my lungs, it makes a man feel. It tingles my tailbone, riles me up, gets me thinking I can go anywhere, do anything. “Anywhere” and “anything” ends up being my parents’ house on the outskirts of Lawton, Oklahoma’s sixth-largest city, where I’m fated to spend the next few days driving a Jeep to and from the non-Starbucks coffee shop in town and fiddling with my laptop. I’m aware of this reality. But reality tends to fly from me and melt into that azure Forever domed over my head upon my every arrival. I have to imagine this not-not-libidinal experience, the ecstasy of wide open space, is what pioneers, settlers, and this land’s posterboy, the American cowboy, once felt when beholding it—the West, neverending.

Oklahoma City Reaches For The Heavens

Legends Tower, if built, would be the tallest skyscraper in the United States, overtaking One World Trade Center in New York City by 131 feet to stand at a dizzying 1,907. This would make it the tallest building in the western hemisphere, and sixth-largest in the world. It’s difficult to communicate just how dramatically its completion would transform the Oklahoma City skyline, but picture, if you would, a pancake with a yardstick plunged into it.

I was as intrigued as I was dubious when I caught wind of the proposed structure while sitting in a coffee shop in Brooklyn in June 2024. Legends Tower, developed by California-based Matteson Capital and designed by Cali-based architecture firm AO, had recently been approved for “unlimited height” by the Oklahoma City Council. It also sounded, apropos of its name, like it would never be built.

However, if all goes according to the plan, Legends Tower will have a glass facade and be accompanied by three equally new but altitudinally lesser towers. A spire will inch the Big Okla-huna over the finish line to achieve “tallest” status. There will be a hotel, offices, and an allotment of affordable housing. That last bit is crucial, and something to keep in mind. Rapidly-growing OKC is staring down a housing crisis with climbing homelessness and eviction rates. The city needs some 77,000 more rental units for low-income residents to compensate. There will also be a “lagoon.”

Some hurdles obstruct Bricktown’s path to the heavens. Testing must be done to see how the tower would hold up to our tornadic winds. The Federal Aviation Administration has expressed concerns about if the structure might impact flight paths. Economists have cast doubts that a city as small as OKC—population 712,919—can really accommodate a supertall.

Sitting in my coffee shop in Brooklyn, I threw my lot in with the naysayers. To be honest, something about the whole thing offended me, such that I found myself itching to pursue what I perceived as a compelling mystery at its foundation: Who the hell do we think we are?

To my mind, there was something fundamentally un-Okie about chasing such a superlative as “tallest skyscraper this side of the Atlantic.” Are we not a more humble set? Isn’t this the sort of hubris we associate with godless coastal elites, what with their hustle and their bustle and, shoot, I don’t know, their daily murders in the subway system? A glassy supertall just wasn’t our style, wasn’t reflective of our values.

A sample of those values: Years ago, back in Lawton, strapped to a dentist’s chair for a cleaning my mom forced me to get while home for a visit, I mentioned to the assistant between violent scrapings that I lived in NYC, and she gave me that stock reply all NYC transplants hear at some point back in their native hamlets: “I’d like to visit, but I could never live there,” delivered in a tone politely gesturing toward a vague contempt.

(Those interested in my rebuttal: “Hnnggffhh.”)

As an Okie, it was impressed upon me that big cities like NYC, LA, and maybe even Chicago were for loonies of a less practical sort, for dreamers (in the derogatory sense), the type of people who watched too many movies or had misplaced confidence in their musical abilities. We salt-of-the-earth folk, meanwhile, were to shake our heads at their foolishness before going back to tilling, or whatever.

I ended up being one of those loony, impractical dreamers, yes. But doesn’t that just mean the math checks out? This is perhaps why Legends Tower felt non-Euclidean to me, why news of its construction hit rather like my dad calling me up to inform me he was pursuing a career on Broadway.

I don’t mean to say OKC doesn’t deserve iconic architecture. Far from! I simply think that buildings should reflect the character of a place, like how Santa Fe is all adobe and how Dallas looks designed by a sentient Ford-F150. Personally, I’m a stalwart proponent of massive, tornado-resistant domes that, if constructed, would give our state capital a unique and slightly unnerving sci-fi vibe, postcards of which would surely sell like hotcakes in the domed visitor center lovingly named, you guessed it, “The Welcome Dome!”

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter, The Talegate

The point is, a city’s skyline ought to be a man-to-land conversation where both sides get to talk. See, for example, Prairie School architecture, a style that embraces horizontal lines in homage to the American plains, championed by Frank Lloyd Wright. A vertiginous skyscraper in OKC, meanwhile, would register as a crude and off-topic interjection—“Mine’s the biggest!”—and I never took us as the types to interrupt. We’re famously polite! Such naked ambition, in addition to being unbecoming, is also kind of sad in what it reveals, like a short man announcing plans to undergo that procedure that adds an inch to your height by shattering both femurs. I suppose I thought, pardon the phrasing, that we Okies were above that.

Whoever was behind Legends Tower (California, apparently) was attempting to erect a monument to everything we weren’t, a public declaration that in fact we did harbor aspirations of being like those city slickers we’d always professed to not care much for. Feeling stirred, I decided it would be worthwhile to dust off my “journalism and mass communications” degree from the U of O and get to the bottom of all this.

It Goes All The Way To The Top

Like any proper detective, I needed a base of operations. My apartment in Brooklyn wouldn’t do. I wanted the film noir fantasy. I booked a room in the Skirvin, OKC’s preeminent haunted hotel. The grand art deco building is said to be haunted by Effie, a horny Prohibition-era ghost. She appears most often, per reports, to pro athletes. The original story goes that Effie jumped to her death from room 1015 while pregnant with the lovechild of the hotel’s founder, W.B. Skirvin, who was quite the womanizer and married at the time. Lakers player Metta Sandiford-Artest (formerly Metta World Peace (formerly Ron)) claims she sexually assaulted him in 2016.

The last time I’d been at the Skirvin was as a junior in college. I’d matched with a much older man on OKCupid visiting from LA; he worked in Hollywood and told me he’d buy me dinner if I wore my cowboy boots to meet him in the lobby. I’d left my boots back in Lawton, so we’d negotiated instead that I would wear glasses. “I guess I like guys in glasses,” he’d pouted. All I had were an oversized fake pair from Urban Outfitters, and these I removed during our dinner in protest of the fact that he only wanted to hear about the cows and horses in my backyard, and nothing about my screenplay set in a post-apocalyptic world in which squids had achieved super-intelligence and were hunting my bald, teen protagonist. I don’t recall why she was bald.

So, the Skirvin was haunted in a few ways. But I figured one “legendary” piece of architecture deserved another, and it would be a sumptuous backdrop for my investigation into Legends Tower. There was even a piano bar downstairs where I could conduct interviews with shadowy figures wearing trench coats and fedoras at a rakish tilt. After checking into my room, which was stately and cold in the way only hotel A/Cs can achieve, I commenced playing journalist. But I didn’t actually know where to begin. I must have skipped that day in college. Something about an inverted pyramid? I called my mother.

“The what?” she said when asked if she’d heard of Legends Tower. I filled her in. “Why are they doing that?” she asked. I explained why I thought they were doing that. This was followed by a long verbal shaking of her head about our priorities as a state, about how our public schools didn’t have desks, about how the inmates were running the asylum, which segued seamlessly into her evergreen topic of psycho-analyzing Donald Trump, an exercise that always ended with, “but I’m done worrying about all that. They lost me. I’m out.”

Aside from my mother, your amateur muckraker found few people willing to speak about Legends Tower on the record. This lent a somewhat thrilling, definitely ominous energy to the thing. I reached out to AO, the architectural firm, and was met with crickets. I reached out to a popular YouTube channel that had publicly expressed concerns over the proposed height of the building. Nada.

The only people who would speak to me about Legends Tower and thus confirm it wasn’t a fever dream of mine were journalists in OKC (with perfect attendance in college, I guess) who’d reported on it themselves. While most agreed that something would probably be built, they were uniformly dismissive of the whole “let’s do the Burj Khalifa in the Heartland” thing, its legislative approval from the City Council notwithstanding.

“I don’t mind telling you that I just don’t think it’s gonna happen,” Steve Lackmeyer of The Oklahoman told me, not in the piano bar, but over the phone, and probably not in a trench coat. “I can see the smaller proposed towers around it being built. But the giant tower? No.”

Next, I called up a friend of mine from OU who now works in politics. He was aware of the project. “Oh, Oklahoma,” he said. “It’s like Abu Dhabi, but the government has no money.” He was also able to give me my first real lead: “You ought to talk to James Cooper. He was the one ‘no’ vote on the City Council.”

'America's Biggest Penis In Bricktown'

My Zoom meeting with City Councilman James Cooper was something I could have just as easily accomplished in Brooklyn, but whatever.

Cooper was, as my source had said, the lone person unwilling to give Legends Tower the go-ahead to pursue biblical heights. We’d met once before, in the Other Room, the bar attached to Picasso’s in the Paseo, some lifetimes ago. I was fresh out of college and passionate about moving to either coast, didn’t care which, and becoming a writer. Cooper was passionate about local politics and about OKC, its potential. He pursued a career in government, and actually made good on his plans. In 2019, he became the first openly gay man to serve on the OKC City Council.

Sitting in my room at the Skirvin with the A/C set to a subarctic temp, James’ friendly, freckled face appeared on my laptop. We exchanged Zoom-waves. “It’s been a while!” I said.

“It has!” he agreed. “I hear you want to talk about America’s biggest penis in Bricktown.”

“I sure do.”

Cooper, as it turned out, had at first been on board with Legends Tower, thinking it might help mitigate OKC’s housing crisis. But he became leery of the finer details, details that, when I asked about them, led to a heroically patient attempt on his part to explain to me what a TIF (Tax Increment Filing) was, and how it was germane to the proposed structure. I was coming perilously close to giving up on my very formal investigation and leaving it to someone who “understood the economy” when James brought the conversation back down to a level I could wrap my brain around.

“I got weird vibes from the nonprofit, Aspiring Anew Generation,” he told me. “Their website looked like something a college student would have created the night before their graphic design project was due.”

My eyes uncrossed and my gossip receptors activated. I leaned forward in my chair. “Say more?”

When pitching the project to the City Council, Matteson Capital had proposed an affordable housing component. 132 rent-subsidized units would be set aside for individuals who’d struggled with homelessness. These individuals would be paired with a case manager or support staff and provided, per their needs, addiction counseling and financial literacy assistance. This was all to be overseen by a nonprofit organization, Aspiring Anew Generation, [sic] and [sic], based in Arizona.

“I pulled up the website while the developer was present,” Cooper said, “but nothing was clickable.”

I opened the website. An unclickable link titled “Our Staff” featured an obviously AI-generated1 Black woman wearing aviator glasses confidently stepping into a bright new tomorrow. Photos of “Our Volunteers” showcased the brave participation of mutants with appendicular deformities not yet recognized by science. A picture of two hands shaking counted a dozen fingers, a bewildering choice of image considering there’s no shortage of royalty-free stock photos of handshakes available, implying a firm commitment by Aspiring Anew Generation (AAG) to sourcing all visuals straight from Uncanny Valley.

As for its head honcho, Dr. Jessica Stanford, her “about page” at least featured a photo of a real human, which was promising. Titled “DR. JESSICA STANFORD: A BEACON OF RESILIENCE AND HOPE,” the page featured vague, adulatory prose and read like the kind of literature state media might proliferate on behalf of a despot it didn’t actually know much about. “Dr. Jessica Stanford's story is a testament to the incredible strength of the human spirit,” it said. “Growing up in a tumultuous environment, she faced hardships that would have broken most people.”

The page went on to address Dr. Stanford’s critics in a section titled “Battling the Naysayers,” which struck me as an oddly combative tangent for an affordable housing nonprofit’s website. “As is often the case when individuals dare to challenge the status quo, Dr. Stanford faced her fair share of detractors,” it read. “Negative comments and false accusations came her way from those who sought to undermine her work and her organization’s mission. It would have been easy to be disheartened, to retreat into the shadows once more.”

I enjoyed this paragraph for how it portrayed Dr. Stanford as a kind of malevolent entity that would “retreat into the shadows” from whence she came. But the entire thing stank of ChatGPT, which has a tendency to produce images and text that are somehow both glossy and lightless. “I showed the website to my students,” Cooper told me. “It was very embarrassing.”

“James,” I said. “I don’t think this org is legit.”

There's Even A Lagoon

After ending my call with Councilman Cooper, I began digging for information about AAG with the zeal of a penniless pirate bequeathed a treasure map. I started with an extensive search on Dr. Stanford, but the only thing I could find was a sparse LinkedIn page featuring the same photo from the website. I looked up “Jessica Stanford Arizona,” as well as “Jessica Stanford PhD,” and other iterations on this theme. Her online presence was incredibly limited. She does her beaconing of hope offline, it seems. Good for her!

Next, I came across an article by Actual Journalist Matt Patterson at NonDoc, which helpfully included a YouTube video of the City Council meeting in August of 2023, where Scot Matteson of Matteson Capital and AAG CFO Joanne Carras delivered their presentation. Matteson, a man in his 60s, slightly disheveled in that “Richard Branson” rich-guy way, introduced himself as the developer of L.T. before listing off his bonafides—high-rise condos, resorts, office buildings, a project in Miami he called “the largest project in U.S. history.” He used the words “I built.”2

The Matteson Capital website lists the Miami Worldcenter along with a digital mockup of it under a section titled “Portfolio,” along with the suggestion to “Explore Our Current & Past Projects,” though nothing is clickable, including the “Board Walk at Bricktown” project, otherwise known as good old Legends Tower, its concept art featuring a skyscraper so tall it extends beyond the border of its allotted pixels. Looking for more on Matteson himself yields little but stories from the New York Post associated with his time dating Real Housewives of Orange County cast member Shannon Beador back in 2018.

Returning to the video, Matteson then invites Carras to “talk about the numbers.” Carras, like Matteson, opens with her curriculum vitae. Most important, she says, was her service as a deputy mayor of Los Angeles. “I was the one recommending all the money to go to the lower-income marginalized communities through the developers that were willing to take the risk to change those communities back to vibrant areas with new housing and jobs,” she says. “All the projects have been extremely successful over the years.”

After going over the promised features of the project, including the lagoon (despite my cynicism, I find myself rooting for the lagoon), and a mockup for two of the smaller towers that for some wild-ass reason are called “the Twin Towers,” Carras opens the floor for questions. Councilwoman JoBeth Hamon asks about the housing component. Which local groups have they worked with so far? Carras says that, due to scheduling differences, they’ve been unable to meet with many, but they do have a list of potential collaborators.

“Our founder and chair, Jessica Stanford, is here,” Carras says, gesturing toward an unseen Jessica Stanford, compounding the latter’s “secret final boss” vibe. “She’s met with some of the local tribes. Indian. Natives.”

Carras is asked to explain what, exactly, the nonprofit is. “The name is Aspiring Anew Generation,” Carras says, [sic]-ly. “That’s a very deliberate name, ‘generation,’ to break the generational continuum of trauma and other difficulties in your life.” She goes on to say that the nonprofit focuses on the unsheltered and the chronically homeless, helping them to get back on their feet with a success rate of over 90% (she looks back at, I assume, Stanford, to confirm this).

“Our founder has experienced those things in her life,” Carras goes on. “She’s an inspiration to everyone she helps.”

Next, Councilman Mark Stonecipher speaks up. “First of all, I want to thank you for choosing Oklahoma City,” he says. “I look forward to working with you all on this.”

Following this, Cooper expresses enthusiasm, but also reluctance. “Like many places in the country, we’re experiencing a housing crisis,” he says. “And as this project became public news, I heard many from Ward 2 saying, ‘You’re gonna give them money for what? Can I afford [it] if I’m a teacher or social worker?’”

In response, Carras affirms AAG’s mission, saying that some individuals might even pay zero rent, depending on their situation. “With the philanthropic partner we have [with] Mr. Matteson as the developer … I've been his financial advisor on this project, but somewhere in the process … I became an officer of this nonprofit, another passion of mine,” she says. “So I had to ask, could you please include us? Inclusive, right? Our program? And he said ‘yes.’ It’s not often you see this inclusivity … so, the rent could be zero.”

The OKC City Council, after this meeting, would vote 7-2 (Hamon joined Cooper in voting “no” in this initial vote; Cooper was the lone “no” vote in the second) to approve the Boardwalk at Bricktown project’s TIF funding3—giving Legends Tower permission to pursue the good Lord above. While approval of the TIF wasn’t contingent on AAG’s participation in the project, AAG’s claim of a 90% success rate transitioning the chronically homeless into housing was, well, aspirational. For a population that faces so many obstacles, it’s unheard of.

Matt Patterson’s 2023 article mentions that AAG was among the 156 providers identified by the state agency as having “a credible allegation of fraud” and was implicated in a crackdown on fraudulent Medicaid billing. Per reporting in the Mesa Tribune, the crackdown came as several of these service providers were suspected of charging the state for incompetent or even nonexistent care.4

I reached out to Patterson at NonDoc for help getting in touch with Carras, and he kindly sent me an email address. I reached out to see if she or Stanford might be available to chat and received no response. Shortly thereafter, the AAG website was taken down.

That was about a year ago. Even before my very formal investigation, Matteson had already gone out of his way to distance himself from AAG, telling the New York Times, “We do not have a contractual relationship with them.” I’d been beaten to the punch. Still, I could have written a story. I’d gone through all that trouble, had booked a room in a haunted hotel, had conducted some interviews, had watched a three-hour City Council meeting, and so on.

I could see the outline—meddling Californians set out to build the Tower of Babel in the Heartland; a shady nonprofit gets involved; a gay Black man becomes the lone voice of reason; hubris and folly in the West. But every time I wrote anything down, it was like the story lost something. I guess I liked it more in my head.

I never made it to the Skirvin’s piano bar.

“What do we want with this vast, worthless area, this region of savages and wild beasts, of deserts, shifting sands, and whirlwinds of dust, of cactus and prairie dogs? I will never vote for one cent from the public treasury to place the West one inch closer to Boston than it is now."

—Former U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster, attributed to his time as a senator from Massachusetts in 1824 while passionately arguing against the development of western territories. One imagines a cigar flying emphatically from his mouth while shouting this.

It’s funny. You can grow up in a place, spend over two decades of your life in it, and still have it all wrong. Did you know Oklahoma isn’t that flat?

In the conversations I’ve had about Oklahoma, conversations on rooftops in Brooklyn or in offices in skyscrapers, I’ll admit that I’ve stolen some valor. “Flat,” I’d say, when asked what it was like growing up where I did. But as a child I could see the Wichita Mountains from my bedroom window. Our house was built on a hill. While it’s true that Oklahoma has prairies and plains, it comes in at a measly 16th in the “Flattest State” contest, with Florida taking home the gold. New Jersey is flatter than Oklahoma, which is barely flatter than New York.

To be fair, a state’s flatness can be measured in many ways. Take, for example, a 2003 experiment where researchers laser-scanned an IHOP pancake to test if Kansas truly was “flat as a pancake,” an experiment they claimed successfully upheld the old proverb, but has since been met with fierce criticism for its methods. One gripe is that there’s a difference between how flat a terrain actually is, and how that flatness is perceived and experienced on a human level; how it’s felt.

Oklahoma, in other words, isn’t necessarily flat. Rather, it’s vast. Immense, extensive, desolate—void. I submit that its vastness, the physical and psychological experience of wide-open space, makes people a little crazy. Let us look at what kenophobes, individuals afraid of vastness, a fear known as horror vacui, have to say on the subject. They purport to dizziness, to feeling like they’re going to pass out, to being overwhelmed by freedom. The lack of boundaries, the absence of anything to visually anchor themselves to, makes them feel “exposed,” “vulnerable,” “detached,” “out of control,” per various internet forums.

This isn’t to say Oklahoma is some kind of kenophobic collective, but to attest that landscapes hold a power that influences people in subtle and unsubtle ways, that the way the eye travels across a terrain has some relationship to how the people who live on it think and feel. In Oklahoma’s case, this helps contextualize our rich history of being complete nutcases prone to manic bursts of energy followed by long, wistful “well, shoot” intervals of time in which we wax poetic about our grand designs not quite panning out. The latter, though its origins are in the former, are often mistaken for our entire deal. Folksy. Humble. Nostalgic. Banjos. Harmonicas.

Our reputation as modest, practical people is promulgated both within and without: Things are slow and still around here, and that’s how we like it, thank you kindly. But on closer inspection, this stillness is more like the lull before the tornado; our twisters are able to achieve such intensity and deal so much damage because there’s little to impede them once they get going. Look at downtown OKC. The local government promised “the city of the future” during urban renewal in the ‘70s, demolishing turn-of-the-century buildings to make way for progress. Then came the oil crash. The ghostly vibe of downtown, before we invested in a winning basketball team, was the result not of a sleepy, simple population, but of a failed tilt at greatness.

Better yet, look at OKC’s origin story, the tale of the city that sprang up overnight. Sam Anderson, writing beautifully on the subject in his book Boom Town, chronicles the absurdity of the 1889 Land Run, an inelegant free-for-all to claim parcels of land that saw the sort of antics one would expect to see in a Hanna-Barbera cartoon: houses on wheels, Frenchmen in hot air balloons hovering over a desired lot. “It seemed,” one observer recalled, per Anderson, “as if some thousands of human beings had gone mad.”

Look at where I grew up. A short 15 minutes away from my parents’ house is Meers, another boomtown, this one the result of what’s now known as “the gold rush without the gold.” Meers, along with other towns like Wildman, Golden Pass, and Oreana, was constructed based on folklore about Spanish gold hidden in caches in the mountains. Whipped into a frenzy in 1895 by the discovery of a primitive Spanish mill, or arrastra, used for pulverizing ore, prospectors trampled over multiple treaties with several Native tribes to mine the land. Six years later, and despite fierce tribal opposition, the area was opened to general settlement. My hometown, Cache, appeared around that time as well.

Meers now, if you’re curious, is a burger restaurant with a menu that makes light of its insane origins. “Meers gold ain’t in them there hills,” it reads, “it’s in the taste.” Visitors can order from a selection of “gold dust desserts,” or try a burger named the “prospector,” or crack open a Meers Gold Beer. No gold was ever found. It was, in the end, just a story.

Boom.

Rush.

Run.

These aren’t words typically associated with a bucolic idyll, or with a practical, no-nonsense sort of people; instead, they conjure up nonsense enthusiasts. Ignore that these things are in history books and museums, and they read like the activities of a desert cult.

For as long as I’ve been alive, the heartland has been sold to me as the domain of “real Americans,” people primarily motivated not by the flashy, distracting, frankly gay issues that people on the coasts care about, like civil rights and trains, but by bread-and-butter issues like the economy and the price of gas. People who fail to listen to these totally normal citizens are described as out of touch and elitist, hence why The New York Times occasionally dispatches a reporter to get a national vibe check from some patron in a diner in a flyover state. Nevermind that such establishments practically cater to transients on their way to Serial-Killerville.

This narrative is worth interrogation. I myself bought into it. But, the older I get, the more complicated it seems. Here’s the nugget of truth buried underneath it all: Oklahoma is for dreamers.

I don’t necessarily mean that in a positive way. Our state’s history has looked like outsiders coming in, enticed by new horizons and the promise of land and gold and possibilities, and pursuing those things as if there were no cost. From the ground level, it certainly looks like the West never ends. It feels that way. But there’s always a cost, and it’s usually borne by someone else. There were people here long before European settlers showed up: the Wichitas roamed the Great Plains for thousands of years before the Spanish encountered them along the Arkansas River in 1541.5 Others were also here before the Trail of Tears—the Osage, Caddo, Kiowa, and Comanche, to name a few— before the U.S. government decided Oklahoma was useless to white settlers, and then changed their minds.

How do Oklahomans reckon with this? We sort of don’t. Nostalgia relieves us from the trouble. Nostalgia organizes the past into a romantic narrative. Through the state, we often view Natives with a reverence,6 but it’s the reverence for old, nonliving things—what a hunter feels for a mounted bison head, maybe—a nostalgic reverence that denies the contemporaneity of the subjects and commits them to the settled score of history, to a time when things were simpler and men were hardier and any grousing to the contrary can more easily be written off as times changing for the worse. Everyone is so sensitive these days.

There’s a rhythm there.

When I first learned about Legends Tower, I thought it went against everything that made Okies who they are. Now, I’m not so sure. The sudden appearance of a supertall tower would, if anything, be in keeping with Oklahoma’s legacy; might even in its brazen singularity be an altogether appropriate monument to the spurts of manic optimism that birthed OKC itself, just another one of those sporadic EKG spikes in our otherwise horizontal history.

The only thing more appropriate, I guess, would be if it were built halfway, and then abandoned.

Pie In The Sky

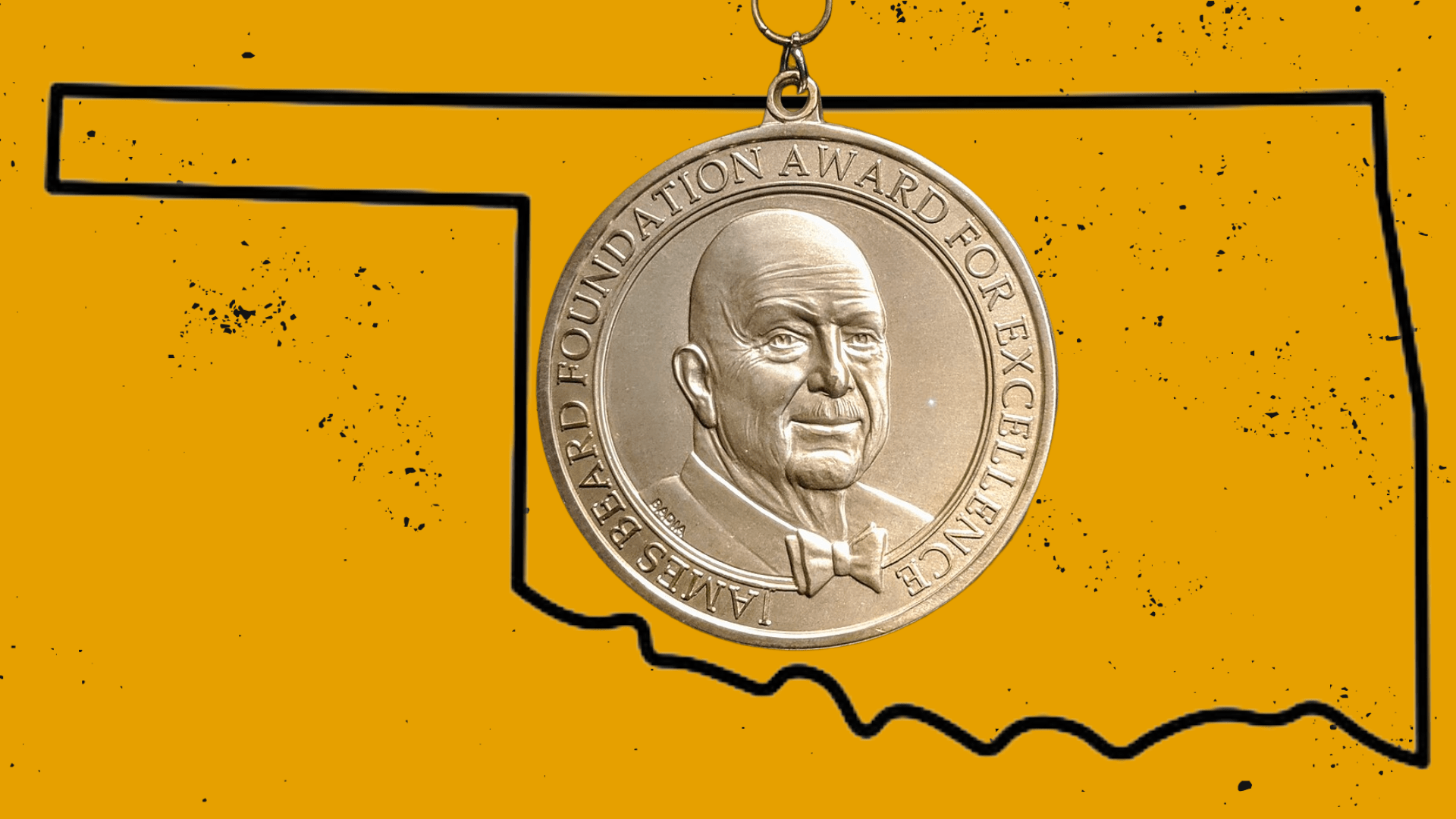

As of today, ground still hasn’t been broken for Legends Tower. But there’s already a tall tower in downtown OKC—Devon Tower, referred to by locals as “The Eye of Sauron” in a manner that’s kind of deprecating but loving, like a nickname for a raggedy one-eyed family pet that bites people. It stands at 844 feet, which isn’t quite “behold the folly of man” tall, but enough for its silhouette to occasionally appear in infographics about notable skyscrapers across the country.7

Built in 2011, several of its 50 stories are, quelle surprise, empty. During my very formal investigation, I thought it prudent to get some idea of what standing at the very top of Legends Tower might be like. I’d obviously need a second pair of eyes with me, to confirm or deny my bullshit.

I invited my friend Colby, a former frat boy with the kind of face exes write songs about, who also happens to be a well-read, gentle soul with a Criterion Collection subscription and a keen interest in architecture. We met up at his office, and he drove us a few blocks8 to the parking garage by Devon Tower.

I’d actually never been inside and had no idea what was up there. I’d always kind of imagined it as completely hollow, like the cardboard core of a roll of paper towels. I couldn’t imagine any people inhabiting it. But while sorting out our agenda, Colby informed me that at the top of Devon Tower there was in fact a restaurant called Vast. At the acme of manmade works in Oklahoma, at the tippy-top of our tallest tower, is … a buffet. The words “pie in the sky” did come to mind.

We decided, of course, to eat there. On offer was beef, fried chicken, and an assortment of those square, spongy little desserts that show up at business conferences and Chinese buffets in the “American Food?” station. The wait staff at Vast was kind and attentive and, because the buffet was self-serve, no one minded when I got up and walked about. I moseyed up to the biggest window and stared out.

There’s this quote from the book The Solace of Wide Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich, a woman who moved from the West Coast to a ranch in Wyoming following the death of her husband, that really cuts to the beating heart of the West, its founding paradox. “Disfigurement is synonymous with the whole idea of the frontier,” she wrote. “As soon as we lay our hands on it, the freedom we thought it represented is quickly gone.”

It’s hard to overstate how depressed the view from Vast made me feel. The sky, which at ground level in Oklahoma inspires such awe, felt taxidermied. It was like seeing some dead great blue heron with its wings articulated by human interference in mock flight; not a wild thing, but one of those glassy-eyed stiffs in a museum or a curio in a tacky bazaar. The observer is permitted to get so close only because the subject is powerless. I attributed this to a total lack of mystique. I was staring out from so high up that I came up against the earth’s curvature. In other words, I’d encountered a hard limit.

Colby sidled up beside me and joined his gaze to mine. We stood in churchy silence for a minute or so.

“Can you see Texas from here?” I finally asked.

Footnotes

- The figure had that impossibly smooth look that AI-generated images tend to have.Return to content at reference 1↩

- That project, the Miami Worldcenter, remains under construction, but technically opened in 2019. Various press releases cite the CIM Group, a real estate investment company, and the involvement of two gentlemen, Art Falcone and Nitin Motwani, in its (near) completion. More information on Matteson’s involvement is hard to come by, though a tract of land purchased by Centurion Partners, thanks to a $12.75 million loan from Fifth Third Bank, is mentioned. Matteson founded Centurion in 2001, with Matteson Capital succeeding it.Return to content at reference 2↩

- I eventually looked it up, okay?Return to content at reference 3↩

- I’m not saying AAG is guilty of this, but the mechanisms of the Medicaid scam as outlined in the Mesa Tribune are straight-up villainous and worth detailing. According to Arizona state officials: fraudulent service providers will target Native Americans living in poverty, entice them from tribal lands, and bring them to homes in and around Phoenix under an org’s purview. The org will then bill the state for the behavioral health services, sober living, and transportation they claim to be providing to the individuals living in their facilities. Darker still, some of these providers were suspected of supplying Native Americans with alcohol or drugs to keep them from communicating with their families and to, Jesus, induce the very problem the orgs supposedly existed to solve (imagine St. Jude’s actively giving children cancer). This practice was so rampant that Navajo Nation created an org called Operation Rainbow Bridge to find and bring Natives back to their tribal lands.Return to content at reference 4↩

- Technically this encounter occurred in modern-day Kansas, but whatever! When you follow buffalo herds around for hundreds of years, you’re going to get lost from time to time.Return to content at reference 5↩

- See, for example, an Osage Nation war shield on the state flag.Return to content at reference 6↩

- Though “We’re #72!” is admittedly an anemic boast.Return to content at reference 7↩

- Summertime in OKC. Short drive totally justified.Return to content at reference 8↩