Leaving campus for lunch was a rite of passage for Tulsa teenagers for decades—until February 15, 1994, when I went to a Wendy’s for a burger and got shot instead.

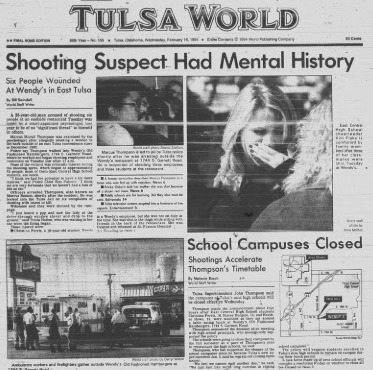

The next day, almost every local campus required students to stay at school. It was a huge shift, causing chaos for school districts, who suddenly were responsible for feeding every single student. And at the center of all this were myself and two other students, along with three Wendy’s employees, on the wrong side of a pistol.

Let me tell you what happened. In 1994, I was a Sophomore at East Central High School. On February 15, a Tuesday, I rode along with a few other girls to lunch at 1744 S. Garnett Rd, which at that point was a Wendy’s Old Fashioned Hamburgers. After buying a square-pattied burger with the change in the bottom of my purse, we sat down near the back of the restaurant to eat while the place filled up with other kids from school.

Suddenly, two loud pops rang out. I thought nothing of it until people started screaming and running for the door. A man wearing a black leather jacket came from the back and started firing a gun. We dove under the table. I’ve always been a storyteller with a flair for the dramatic, and my first thought as we ducked for cover was, “This will make a great story to tell at church tomorrow tonight!”

As the man walked toward us, he shot two of my friends in the leg, and me in the arm; I screamed and cried out for God to help us. Then, he held the gun to another friend’s head and pulled the trigger.

The gun didn’t go off. He tried again. Nothing.

He asked her, “Do you believe in God? Because the clip is stuck.”

Then he walked out the back door.

We were laying on the floor of the restaurant, moaning, when the gunman came back into the restaurant and said something about us getting out of there or he would kill us. We moved quickly. I helped the ones who were shot in the leg up, and we headed toward the door. To get there, we had to pass the gunman, and that’s when he shot me four more times in the abdomen.

Somehow, I made it out the door. I remember thinking, “I’ve been shot; I should probably fall down.” So I leaned up against the building and scooted down onto the sidewalk.

Pretty quickly, people started yelling at me to get up and move. It felt terrible to move, but I’m a people pleaser, and they were adamant. Classmates helped me across the parking lot and into the bed of a pickup truck.

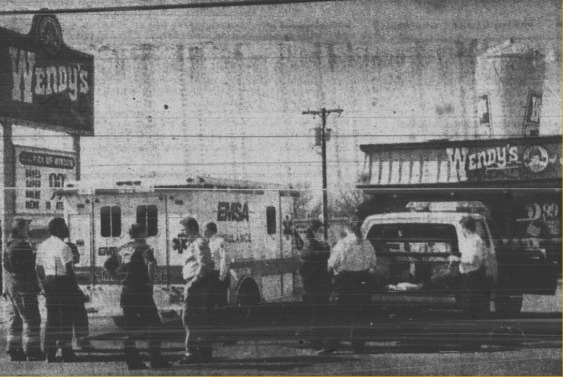

As soon as that happened, the gunman walked out the door, right where I had been laying. From the truck, I heard the police arrive and make the arrest. I also heard the gunman saying something about his shooting being a double murder, like he was excited.

I’m not sure how long I was in the bed of the truck before the paramedics got to me—it felt like years. A fireman named Cole cut off all of my clothes in front of everyone so he could see the bullet wounds. That was embarrassing. My best friend's brother was there that day, and every once in a while, I ask him if he remembers seeing me naked. He never answers.

I was taken to St. John’s (what’s now Ascension St. John) in an ambulance. I remember the EMTs saying things like, “It’s not good.” I knew I’d been shot multiple times, and I assumed that I was going to die.

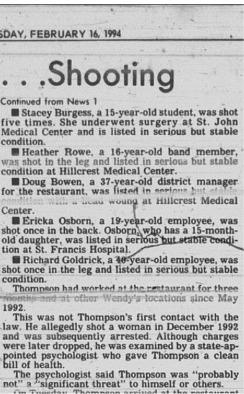

I was taken into emergency surgery, where they made an incision from just below my chest all the way down my abdomen to assess the damage. I’d been shot five times, and they said the bullets missed my vital organs by less than a millimeter.

I remember asking a nurse in the ICU if I was going to die later that night. She told me, “not today.” After repairing my small intestine, and two weeks in the hospital, I was mostly physically ok.

The gunman, Marcus Muriel Benson, worked at that Wendy's. He struggled with drugs and mental illness. His motivation may have been unrequited love from one of the other women who were shot. He pled guilty and was given six life sentences.

In all, six people were shot: three students and three Wendy’s employees, but luckily no one died. Benson is still in prison today.

Sometimes getting shot when you're fifteen can boost your social status. I got to meet the governor a few times, I had lunch with Dave Thomas, and I was elected to student council. Boys literally came up to me and kissed me in the hallway. Everyone knew who I was, and was glad I was ok. Almost dying makes you cool. Still, if you can avoid it, I don’t recommend it.

I developed PTSD, though I didn’t know what that was at the time. The world didn’t feel safe to me anymore. Fireworks and eating out were hard for me.

Like many people after a trauma, I sought healing from multiple outlets. I clung to religion, my work, relationships, and, crucially, desserts. I looked for answers to help me understand what I was experiencing, like nightmares, anger, and moments of extreme fear. It wasn’t until a few years later I was reading a book and realized I had PTSD. I decided to study Social Work and became a therapist specializing in trauma. Helping people who experienced something similar gave meaning to what I’d been through, and life started to make sense for me.

About ten years after the shooting, I felt the need to write Marcus Benson a letter. I told him that I forgave him for what he did, and that I was okay. I told him that that one moment didn’t have to define his entire life, and that I hoped he could find peace. I signed it, “Your friend, Stacey.” He wrote me back and thanked me for the letter. He said he hoped I was okay, and that my forgiveness meant a lot to him. He said he was happy that I called him my friend.

The ripple effects of what happened that day are still felt in Tulsa. Most school campuses are still closed for lunch. A twenty year old girl recently told me that her parents often brought up the shooting as a reason she couldn’t go anywhere without them. Trauma has a way of doing that: it reminds you that bad things are possible, and we don’t always have control over what happens to us. We lost more than just the freedom to leave campus; we lost our sense of safety.

That said, I gained more than I lost that day. The path of healing and forgiveness I took has helped me face other hard times. When something is tough, I like to think, “I’ve been shot before, this can’t be as bad as that!” There is a term called: post traumatic growth. It refers to positive psychological changes that sometimes occur after a traumatic event. It’s a process where a person not only copes with their trauma but emerges with more meaning and purpose in their lives.

There’s a lot of evil in the world. Terrible things are happening all around us that we have no control over. Instead of letting the bad overwhelm me, I am determined to be a force for good and help others heal.