Watching the current onslaught of mass deportations and state-sanctioned killings of nonviolent protestors, bystanders, and ordinary citizens, I’ve found myself at the edge of hopelessness, dread sinking further into my chest with each echo of a gunshot. I’ve struggled to pull a coherent thought together that isn’t how much more of this can we take? And then I remembered: We’ve been here before.

In fact, we’ve been here quite a few times. Many in the social media echo chamber have argued that we are witnessing the formation of a new “gestapo” here in the U.S. Others have rightly disagreed. We needn't compare ICE to foreign historical powers when our country has its own history of violent militias with government ties. In Tulsa, it happened in our own back yard.

Many Tulsans are aware of the Race Massacre of 1921. Many still aren’t. My mind keeps coming back to it as I watch masked individuals take lives and brutalize communities across the country, empowered by our government—just as they did on the evening of the Massacre, when Tulsa Police deputized hundreds of white men in an effort to quell what they saw as an uprising in Greenwood (and what was, in reality, a community coming together to protect one of its own). According to a 2025 report by the Department of Justice, nearly 500 men were deputized in under 30 minutes, many of whom had been drinking and instigating violence. Within two days, 35 blocks were destroyed, 300 people were killed, more than 800 were injured, and the coverup began. Bodies of victims were buried in unmarked graves, local papers like the Tulsa Tribune contradicted the death toll daily, court cases were thrown out, and the state denied emergency care. Black Tulsans were left to rebuild alone, in a city that would take decades to officially recognize the severity of the crimes those citizens had endured.

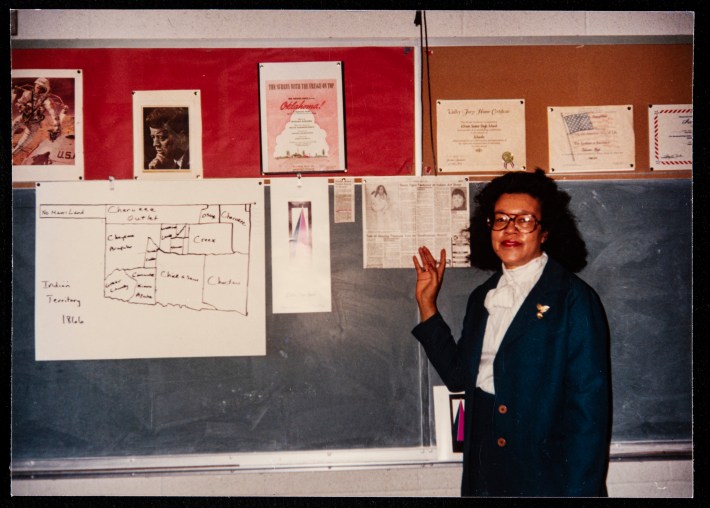

But Greenwood did rebuild. Survivors found ways to tell their stories, thanks in part to community historians like Eddie Faye Gates, whose archival practice honored survivors and their descendants, whose activism forced Tulsa to reckon with its past, and whose legacy still reverberates throughout the city five years after her passing. In a time when a phone video or a voice note can mean the difference between an act of violence being plausibly deniable and being utterly indisputable, Gates’ work feels prescient and more vital than ever.

In honor of what would have been her 92nd birthday, I’d like to pay respects to this remarkable woman—historian, educator, and pillar of her community—whose work still calls us to witness, document, and persist in telling the truth.

The Past Is Present

Born on February 5, 1934, Eddie Faye Gates was raised on a small farm in Preston, Oklahoma, an unincorporated town near Beggs on Muskogee land. Her grandparents, whose own parents were enslaved on a cotton plantation in Texas, fled to Indian Territory in 1904 to escape the oppressive and violent racism of the South. They envisioned Indian Territory as a kind of haven, where Americans could build a new future unburdened by racism and class status. Gates later admitted this dream didn’t quite play out the way her family had anticipated, but it was at least better than Texas.

In her book Miz Lucy’s Cookies: And Other Links in my Black Family Support System, Gates describes her childhood as privileged, but not because of money or class. “If we had had choices, this is what we would have chosen, for our family had so much love, strength, faith, and discipline!” she writes. “We would need that love, strength, faith, and discipline to overcome all the harshness of life that confronted poor Blacks at the time. We were of strong ancestral stock and we did survive.”1

Hopping between small towns throughout her childhood, Gates writes about her early years with a romantic eye, cherishing the people who impacted her life in big and small ways: her neighbor Mrs. Foreman, who helped deliver Gates’ siblings and whom Gates continued to visit well into old age; her eccentric grandfather, who would appear randomly at the end of the driveway unannounced, having walked seven miles from Okmulgee to Preston; the white shopkeepers in the unincorporated town of Pumpkin Center, who taught Gates that “love, compassion, and true brotherhood can exist” regardless of race or creed.2 Gates treasured each of these connections and made hundreds more throughout her lifetime, adding them to her links of support and supporting them, in turn. Every person she encountered became a member of her community, and every person was worthy of love and respect.

Gates developed her love of history at a young age by listening to her Uncle John’s stories about early Oklahoma: “From him, I heard about early migrations, tornados, dust bowls, living and dead outlaws, and other bits of history that intrigued me.”3 She was an avid reader and writer, keeping a journal all her life, and eventually graduated high school with honors. She attended Tuskegee University in Alabama, where she expanded her love of learning into a lifelong passion for activism. She also met her husband, Norman, there, and they eventually returned to Tulsa in 1968.

That same year, Gates began teaching history at Edison High school, only the second Black teacher to be employed there. As a lifelong learner, Gates adored teaching, and continued to teach for 22 years before her retirement in 1992, when she began to travel the world in pursuit of more knowledge. She was particularly interested in learning about historical atrocities, and spent her time in Europe, Southwest Asia, and Africa expanding her understanding of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Holocaust.4 These experiences impacted her deeply, and would inform her later work on the Tulsa Race Massacre, which she would devote the rest of her life to researching and honoring.

The “pinnacle experience” of Gates’ research was a visit to Washington, D.C. on behalf of the Oklahoma Commission to study the Tulsa Race Massacre. There Gates had the opportunity to pore over historical records at the National Archives, Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution and more. She reveled in the experience of physically handling the fragile documents and memorabilia. But there was an important piece missing: Where were the stories from survivors?

Gates brought that question home with her to Tulsa. By the 1990s, many of the survivors of the Race Massacre were quite old, and some had already passed on. Generations of survivors and their descendants had held their stories close out of fear, or because the pain was still too near. Realizing that an irreplaceable breadth of knowledge would soon be lost to time, Gates galvanized her community and began documenting their stories and memories. She compiled these oral histories into two powerful books: They Came Searching: How Blacks Sought the Promised Land in Tulsa and Riot on Greenwood: The Total Destruction of Black Wall Street.

The importance of these books cannot be overstated. As Gates puts it in Riot on Greenwood, “These poignant, personal, penetrating accounts of the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 will not be found, in this magnitude, in any other book or anywhere else. They are all from the people—Black, white, and other racial, ethnic, religious and cultural groups—who observed this riot with their own eyes and who shared it with their heirs, and with anyone else who would listen.”5

When I asked Chief Amusan—descendant of Greenwood, owner of The Real Black Wall Street Tour Company, author of America’s Black Wall Street, and President of the African Ancestral Society—about the impact of Gates’ work, he emphasized that her reach is felt beyond Tulsa. “Her work safeguarded survivor testimony at a time when institutions failed to listen and when silence was easier than truth,” he told me. “Because of her dedication, the voices of those who lived through the destruction of Black Wall Street were not lost to time. She did more than record history, she protected it. Her efforts made it impossible for this nation to deny what happened in Tulsa in 1921.”

Gates did more than just prevent this history from disappearing; she made it accessible. As an educator, Gates suffered from what she called “compassionate teacher syndrome,”6 in which she found herself incapable of keeping knowledge to herself but rather wanted to share it with anyone and everyone who would listen. “You don’t have to be of any particular age, race, religion, or class to receive this information, and you definitely don’t have to ask for it,” she writes in Riot on Greenwood. “You just have to be perceived by the teacher as being in need of it.” She took photographs of everything, interviewed everyone she could, compiled her research into scrapbooks, and eventually published tomes of valuable information. Her archival collection at Gilcrease Museum—which contains more than a thousand items, from handwritten research notes to audiovisual records—is available for anyone to view.

Taking Back The Narrative

But her life’s work isn’t just the extensive research she did, or the facts she uncovered. It’s the connections she made with real people as she listened to their stories. Gates understood that history isn’t all fact. Sometimes, it’s feeling. That feeling moves forward in time as well as back: One of Gates’ students, Lee Roy Chapman, often cited her as a guiding force. It was in her class at Edison High School that Chapman first learned about the Tulsa Race Massacre, spawning a lifelong dedication to amplifying histories that Tulsa has kept hidden.

Eddie Faye Gates didn’t view tragedy in numbers. She saw through statistics, newspaper articles, and textbooks and found the beating hearts underneath. She found love and despair, fear and hope. Community wasn’t an empty word, but something vital, something worth protecting and empowering. By speaking with survivors and documenting their stories, Gates helped Greenwood take back the narrative and find a path toward healing and reparations.

We can do the same right now. Recording injustice is easier than ever, and knowledge, as they say, is power. “What Eddie Faye Gates started, and what people like Lee Roy Chapman and myself have continued, is about reclaiming narrative power,” Chief Amusan said. “When you document truth, you take control away from systems built on silence and distortion.” As difficult as it is to watch death and suffering across the globe, we must continue to bear witness. This is more than going live on TikTok or sharing an Instagram graphic. Don’t just observe; record facts, document key details, and preserve footage. This resource provides an excellent toolkit for documenting injustice and state-perpetrated violence.

Gates showed many, including myself, that archiving is a revolutionary act. We have a duty to record injustice, to protect our neighbors, to amplify the voices of survivors, and to force those in power to reckon with the past. For Tulsa Race Massacre survivors and their descendants, the events of 1921 aren’t stuck in the past. They are relived daily, and we owe it to them to listen. Listen to your elders, your neighbors. Call them, check on them, stand in between them and those who would do them harm. Tell their stories.

Tulsa has a lot of work to do to move forward. So does the nation as a whole. If we follow the example of Eddie Faye Gates, I think we have a chance.

Footnotes

- Miz Lucy's Cookies, p. 22Return to content at reference 1↩

- Miz Lucy's Cookies, p. 51Return to content at reference 2↩

- Miz Lucy's Cookies, p. 61Return to content at reference 3↩

- Riot on Greenwood, p. 23; biography in the Gilcrease Museum Eddie Faye Gates Tulsa Race Massacre CollectionReturn to content at reference 4↩

- Riot on Greenwood, p. 30Return to content at reference 5↩

- Riot on Greenwood, p. 25Return to content at reference 6↩