Fake stories of sports mascot deaths are making the rounds—and pointing to a pattern of fake news scams targeting sports fans across the country.

When I heard through word-of-mouth that a performer behind the OKC Thunder’s Rumble the Bison had died, I had to go sniffing for the proof. That search led me to a Facebook post.

The post, which has since been deleted,1 read, “The Oklahoma City Thunder community is deeply saddened by the sudden passing of the student who portrayed the Rumble the Bison mascot following an accident. Fans and the organization are coming together to remember and honor the dedicated performer who brought energy and joy to the team and Thunder games.”

It was published on January 17 by a Facebook page called “Shai & the Storm,” purportedly an OKC Thunder fan page that “celebrates the rise of Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and the electrifying energy of the Oklahoma City Thunder.”

The thing is, it’s fake. Landis Tindell, a spokesperson and manager of corporate communications for the Oklahoma City Thunder, confirmed by phone on Monday that no performer who plays Rumble the Bison in any capacity for the Thunder has died in the last month.

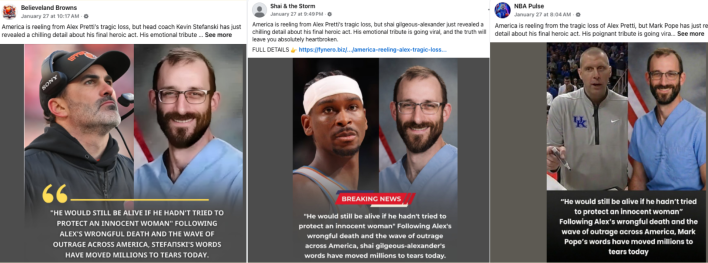

Each post by “Shai & the Storm” follows a similar pattern. First, a divisive, surprising, or otherwise dubious news item such as Karoline Leavitt mocked Shai Gilgeous-Alexander or Shai Gilgeous-Alexander dropped a bombshell about Trump’s 1970 Wharton IQ test or Shai Gilgeous-Alexander revealed a chilling detail about Alex Pretti’s final act is detailed in an image and caption.

These posts are followed up with a call to read the “FULL DETAILS,” linking to a webpage repeating the same copy in the Facebook post—only this page is full of Google Ads. One inspection of the website containing the fabricated story about Rumble the Bison—which still exists, despite the Facebook post having disappeared—revealed at least 25 ads on the page, and a reading of the page’s source code through urlscan.io revealed 37 instances of “adsbygoogle,” a piece of Javascript code that helps Google ads display to a user.

This is part of a growing trend of AI-generated disinformation spread by bots and shell accounts, according to Dr. Rosemary Avance, an assistant professor of communications at Oklahoma State University who studies communication technologies and information access. “These types of posts are disinformation campaigns that often feature manipulated content (e.g., a real image doctored by AI),” Avance told The Pickup via email. “They are also often ‘imposter content,’ in that they try to appear as if they are an individual or organization that they are not.”

What makes it disinformation, as opposed to misinformation? The distinction between dis- and misinformation, Avance said, is one of “intention at the level of content creation.

“When something is created with the intent to trick or mislead, that's disinformation.”

A Bad Week To Be A Mascot

These types of stories were not limited to Oklahoma City. In all, I found at least 66 Facebook pages peddling the same false information about sports mascots between January 15 and January 20.

According to a likely fabricated post by the “Oregon Victory Squad,” a performer behind the Oregon Duck is dead. According to “Hoops Pulse KC,” a performer behind Big Jay died. According to “Big Orange Family,” the performer behind the Tennessee Volunteers’ “Smokey” is dead. Miami Dolphins. Detroit Lions. Arkansas Razorbacks. Notre Dame. Nebraska Cornhuskers. Atlanta Falcons. Indiana Hoosiers. Philadelphia Eagles.

A plague, if you believe the fabrications, upon mascotdom.

Some teams, like the Dallas Cowboys, had multiple separate fan pages pushing the same fabrications: pages like “Dallas Cowboys Update,” “Star Nation,” “Blue Star Brotherhood,” “Blue Star Breakdown,” and “NFL Daily Hype” each posted the same story about the Cowboys’ mascot, with slightly different wording and images, between the 15th and the 20th.

At the time of this writing, the posts pushing the disinformation have been shared a total of 7,076 times.

According to Avance, the OSU professor, these particular disinformation campaigns are intended to mislead readers into taking some kind of monetizable action, such as sharing the post, commenting, reacting, and clicking links to read more.

“Some websites might then also harvest viewers' data and retarget them for additional scams,” Avance wrote. “Meta protects business account (page) owners and avoids transparency, especially when transparency threatens revenue, so the average user cannot verify with certainty whether these pages are legitimate or whether the admins are real people simply by looking at the pages or posts. The fact that these mascot posts are so lazily done, repeating the same content, and occurred in a short timeframe, suggests to me that a particular organization or individual might be behind them, but that's not verifiable.”

The phone number listed by “Shai & the Storm” on Facebook was answered by an employee at Pino’s Italian Restaurant & Pizzeria in Farmville, Virginia, who seemed understandably confused by my question about an Oklahoma City Thunder fanpage. Multiple emails sent to the email address listed on the page were not returned.

This widespread use of Google Ads would seem to violate Google’s “Deceptive practices” policy, which does not allow Google Ads to “be placed on sites … that misrepresent, misstate, or conceal information about the publisher, the content creator, the purpose of the content, or the content itself [emphasis ours],” per an informational video on Google’s ad policy. Emails sent to Google, Facebook, and Meta were not returned.

When you see a shocking, unbelievable story on Facebook, you might want to wait a moment before starting to pray for someone’s eternal soul. You could be seeing disinformation—and potentially falling prey to a money-making scam.

“Right now, an educated user with time on their hands can likely spot an AI-generated image and can do the kind of internet sleuthing [it takes] to discover that this post is not original and that the ‘facts’ it contains are not verifiable,” said Avance. “But most people do not have time or the inclination to do this type of work.”

Avance has several suggestions for those who want to protect themselves—and their loved ones—from such scams. “It's more important than ever for citizens to practice media literacy: Remember that your online attention is currency. Take time to understand who you follow and how their content makes money for themselves or the platform. Learn to verify facts. Avoid engaging with content, no matter how trite the subject, if you haven't verified it; even ‘angry reactions’ on entertainment-type posts are monetizable … and this engagement further trains the platforms' algorithms to favor dis- and misinformation and suppress verified, helpful information. Support local news organizations that you trust by following and engaging with their content and subscribing to their services.”

So the next time you see Rumble the Bison, breathe a sigh of relief. The person inside that costume, while probably very sweaty and tired, is alive.

Footnotes

- I am choosing not to link the Facebook page here, since the information has been verified false, the Facebook post itself has since been deleted, and the links inside the Facebook page and its posts lead to websites whose safety has not been vetted.Return to content at reference 1↩