If you’ve found yourself searching for an analog to this moment of political chaos, consider 1917. The United States was divided over a war in Europe involving Russian expansionism. The president ignored the constitution, cracked down on immigrants, and barely concealed his belief in white supremacy. But the most eye-popping parallel between now and then was the high cost of living. In 1917, the issue of “H.C.L.” was so common the media turned it into a proper noun and gave it its own acronym.

Forget the post-Covid inflation rates of 8-9%. Inflation in 1917 was over 20%, the highest recorded in U.S. history. Labor unions, socialists, and protestors of all sorts urged President Woodrow Wilson to do something about H.C.L. But Wilson looked to his right and saw the real threat to the hegemony of his Democratic Party: Republicans running on the slogan “America First” and accusing the president of allowing America to become a “dumping ground” for immigrants. These Republicans overrode Wilson’s veto of an explicitly racist immigration act in 1917 that forbade entry to the United States of people from the “Asiatic Barred Zone.” “America First” soon became the rallying cry of the Ku Klux Klan, which, by the early 1920s, had completely infiltrated Tulsa’s media and political elite.

But prices were the talk of the day, and every newspaper in Tulsa had theories about why they were so damn high and what should be done about them. The Tulsa Morning Times thought women’s civic clubs could cure H.C.L. with gardening, canning, and dieting. The Tulsa Democrat claimed unchecked immigration from Mexico was part of the problem.

But the readers of the Tulsa World were told not to worry. Tulsa was becoming the Oil Capital of the World, after all. The demand for oil pushed up prices in the Mid Continent Oilfield and widespread prosperity would thus create relief from these high prices. Black gold wealth would trickle down to Tulsa shantytowns where the tap water ran brown.

Meanwhile, readers of the Age of Reason—a new socialist rag in Oklahoma City—got a completely different perspective. Corporate control of food and transportation had created a gilded class of millionaires on the backs of millions of working stiffs. Age of Reason said what many working class Oklahomans felt: “the food situation overshadows all others” and it wouldn’t be solved by gardening or deporting Mexicans. Anyone could see that across town from the new mansions in Maple Ridge were shacks on the Sand Springs Line, where a working man “could stretch a tent” on a plot of land. In nearby oil patch towns like Drumright and Kiefer, roughnecks rented space on top of pool tables to sleep.

Radicals believed they had identified the real culprit of H.C.L.: the capitalist system itself. The Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) advocated direct action against corporate power. This meant strikes, work slow-downs, music, marching and general hell-raising. A minority advocated for violent sabotage of pipelines and refineries.

Oklahoma had one of the most successful Socialist Parties in the nation in the 1910s. At least 175 socialists were elected to local and county offices in 1914, including six to the state legislature. In 1917, angry farmers protested U.S. entry into World War I in rural eastern Oklahoma by starting an armed struggle called the Green Corn Rebellion. Rebels planned to march to Washington on a diet of barbecue and green corn, but the protest was short-lived. They were crushed before they made it to Arkansas.

Rebellion was one thing, but the idea that the oil supply might be sabotaged? That sent a World editor into a paroxysm of rage: “Any man who attempts to stop the supply [of oil] for one-hundredth part of a second is a traitor and ought to be shot!” read an unsigned editorial from November 1917. Labor organizations like the I.W.W. and the Oil Workers Union were “enemies of the country.”

Of the three main newspapers operating in Tulsa at the time, the World was the most proto-MAGA in its attitude toward foreigners. The editor and publisher, Eugene Lorton, had been an investor in the newspaper since 1911, but in 1917 became the sole owner. Lorton wanted tariffs on other nations and deportation of foreigners for those who refused to be Americanized. For those who didn’t meet the vague standard of Americanization, Lorton wrote, “deportation is the only remedy.”1

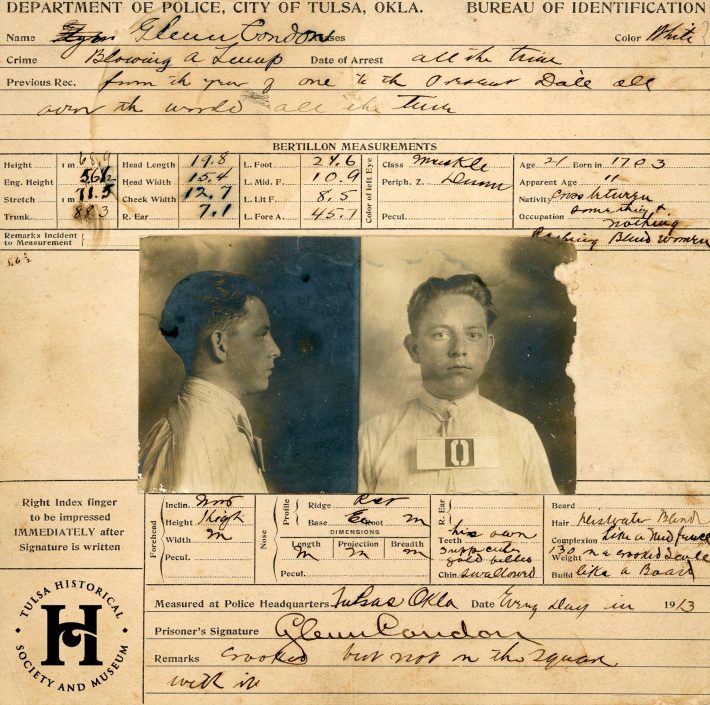

The editorial “Get Out the Hemp,” from the November 9, 1917 edition of the Tulsa World, is notorious among historians, who often cite it as evidence of the violent mood of Tulsa’s elite leading up to the 1921 Race Massacre. Scott Ellsworth, whose history of the Race Massacre remains a keystone text, thinks that this editorial could have been written by Lorton or managing editor Glenn Condon.2 Condon was an odd mixture of journalist, prankster, and vigilante. He doxxed people who did not buy Liberty Bonds, published a faux police report about himself, and participated in a torture session of suspected Wobblies.3 4

Condon and Lorton saw threats to the American way everywhere they looked. And that fear curdled into bigotry. Although Lorton would eventually come to despise the Ku Klux Klan, he wrote that he felt a “thrill of hope” when it re-emerged as a public force. Perhaps the Klan would do what the government had failed to do: “protect the decent, self-respecting, law-abiding element of the population.” The Klan’s slogans of the day had a decidedly MAGA flavor: “One Hundred Percent American” was a popular banner, as was “The City Must Be Clean!”, along with, of course, “America First.”

Bomb Leads to Powers’ Outage

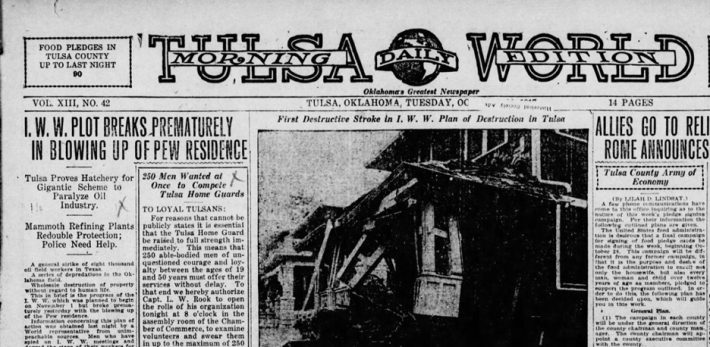

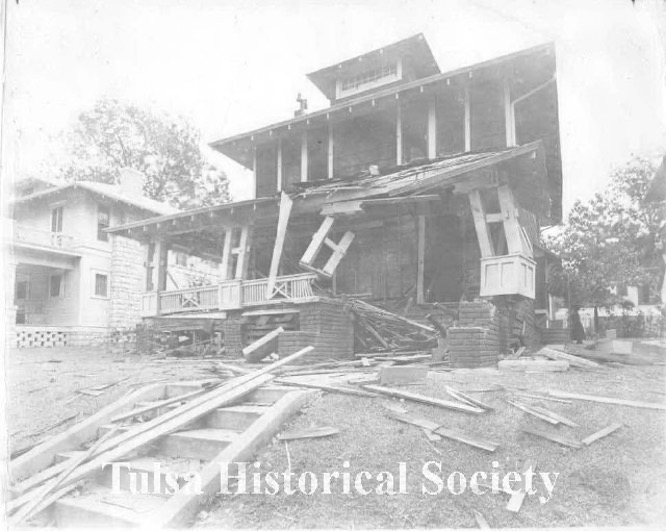

And so Tulsa’s political climate was already in hysterics in the fall of 1917 when the home of J. Edgar Pew exploded. A nitroglycerin bomb went off under Pew’s house near 15th St. and Cheyenne Ave. early in the morning on October 29. Photographs in the World revealed a destroyed porch and damaged windows. Pew was a wealthy oilman who worked for a subsidiary of Standard Oil Co. The World wrote that “the red scourge of anarchy” had descended upon the quiet streets of Tulsa. The Industrial Workers of the World and others were engaged in “a gigantic plot to destroy the property of oil companies and the residences of the leaders in the oil business in the Mid Continent field.”5 The hunt for the perpetrator was on.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of this story in a media ecosystem dominated by newspapers and news wires. The story of a socialist attack on the Oil Capital of the World was picked up by newspapers from Boston to San Francisco, feeding into a climate of paranoia about foreigners and radicals plotting to destroy America. The Boston Globe reported that the bombing of Pew’s porch was the beginning of a “reign of terror.”

The Tulsa World’s reporting of the Pew bombing initially focused on a man named W. J. Powers. Police detectives caught Powers at the Frisco train station in Tulsa after the bombing. Powers’ jittery responses to police questioning left little doubt in the mind of a World reporter that he was the author of “the fiendish act.” Powers was, the World said, an “anarchist” and “bomb thrower” who had “attempted to murder the entire family.”

The piece on Powers was followed up with a front-page call for direct action against this red menace. Glenn Condon helped organize something called the Tulsa Council of Defense, which ordered guns and ammunition from Oklahoma Attorney General Prince Freeling. Think Oath Keepers and Three Percenters, but sponsored by a local newspaper and sanctioned by the Chamber of Commerce. Weapons were handed out to able-bodied men between the ages of 19 and 50. This would be Tulsa’s “Home Guard”—a group of men with no qualifications or training other than being white and hating foreigners and socialists.6

The Guard had to mobilize quickly because the World was “one of the institutions marked for destruction” by revolutionaries. The Home Guard was organized, financed, and supported by leading Tulsa men, including Condon, oilman Robert McFarlin, and S. R. “Buck” Lewis.7

Tulsa police held Powers in jail, and detectives from Standard Oil grilled him, tracing his movements across various oilfields in the southwest and his role in this supposedly expansive conspiracy to destroy capitalism.

But cracks quickly appeared in the World’s reporting.

The World marketed itself as a sober, non-partisan alternative to the Tulsa Democrat, which had a reputation at the time for yellow journalism. Soon to become the Tulsa Tribune, the Democrat was known for explosive headlines, including, most infamously, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator” on May 30, 1921.

But when it came to the Pew bombing, it was the Democrat that pumped the brakes. The main suspect, Powers, had “failed to shed any light on the dynamite plot.” The case against Powers was falling apart, and detectives grew frustrated. A new lead pointed to a trio of criminals who had dynamited a post office in an attempted robbery. Greed, not ideology, was the motivating factor. By November 5, Powers was cleared of all charges.

The “reign of terror” predicted by the Tulsa press failed to materialize. Even the destruction of Pew’s house turned out to be overblown. Upon further investigation, most of the house was still intact; only his front porch was destroyed. These facts didn’t matter to the World. Lorton and Condon were out for blood, and they would soon have it on their hands.

An Outrage in Tulsa

Taken all together, a portrait of Tulsa from 1917 to 1922 emerges. It was a place where civic institutions encouraged domestic terrorism rationalized as patriotism and newspapers amplified fake news. They targeted the enemies within, some of whom will be familiar to modern readers: immigrants, minorities, and socialists, all of whom were eyed with suspicion.

On November 9, 1917, the World published a staff editorial calling for extrajudicial killings of socialists:

Meanwhile, the evidence for the World’s claim that Tulsa was the next seat of socialist revolution continued to dwindle. Two police detectives raided the headquarters of the I.W.W. at the New Fox Hotel, but only found one man at the office.8 It wasn’t clear if he belonged to the I.W.W. at all. Like Powers, he was released from jail and faced no charges.

Tulsa in 1917 was a violent city, to be sure: carjackings, assassinations, and kidnappings happened all the time. The victims, however, tended to be Muscogee women, Black citizens, and labor organizers, while the white oilmen—or their fixers—tended to be the perpetrators, the same people claiming to be “100% American.”

Police detectives picked up 11 men on vagrancy charges on November 6. Municipal Judge T. D. Evans—who would later serve as mayor during the Tulsa Race Massacre—announced a bond of $100. One of the men asked to see a written complaint. Judge Evans said there was no written complaint. A World editor stated a trial was unnecessary. “All that is necessary is the evidence and a firing squad,” the editorial stated.

The men had affiliations with the I.W.W. but all disavowed violence and sabotage as a means of resistance. They did, however, refuse to buy Liberty Bonds, a key financial instrument of the war effort. This, and the fact that many spoke “broken English” was proof enough that the men were traitors and should be executed.

On November 9, the eleven “vags”9 and six more Wobblies were abducted from Tulsa police custody and driven at gunpoint to a ravine just west of Owen Park.10 There, they were stripped to the waist and tied to trees. Car headlights illuminated the men as they were flogged with blacksnake whips until blood ran down their backs. One man was beaten repeatedly with a half-inch lead pipe. As they moaned in misery, other men brought out brushes dipped in boiling tar and slapped it on their backs. Then came the feathers. They were forced to remove their shoes. The self-proclaimed Knights of Liberty then cut away the ropes and shot over the men’s heads, yelling at them to never return to Tulsa. The men disappeared into the crosstimber country of Osage County, half-naked and bleeding. The Knights had prepared barbed wire to mangle the men’s bare feet as they fled into the night.

The World triumphantly reported this event as the day the “modern Ku Klux Klan came into being.” The next day the city “was buzzing with excitement” over the spectacle of public torture. As the men reemerged in small towns seeking help for the lacerations and burns, their story got picked up around the country. In I.W.W. circles, the event became known as “Tulsa Outrage.”11 But the World continued to insist it was a noble act done in the name of the “cheerful spirit” of the good citizens of Tulsa.

The perpetrators of this modern Inquisition tried to hide their identity, but the victims recognized names, voices, and telltale signs of some of the leaders of the Knights of Liberty. Over the years, the victims came to name some names. Tulsa Police Chief E. L. Lucas was alleged to be a perpetrator, as were “Buck” Lewis, J. Edgar Pew, city attorney John Meserve, and Glenn Condon himself.12 The alleged torturers were Tulsa’s leading men: the same people branding the city as the Oil Capital of the World.13

Meanwhile, the Pew bombing remained unsolved. The World published a notice for a $5,000 reward that would lead to the arrest of the “miscreant” who blew up Pew’s home. “The big reward ought to bring results at once,” a reporter noted on November 21. By 1918, Pew himself had left Tulsa for the Texas oilfields. Pew left the mess in Tulsa behind, but would return later in an ill-conceived scheme to pin the bombing on another Wobbly.14

The Outrageous Cost of Living

World War I ended in 1918, but armistice didn’t alleviate the paranoid style of Tulsa politics. Federal reforms brought in by the new Republican administration under Warren G. Harding did little to bring down prices and H.C.L. persisted. To make matters worse, the price of oil collapsed in 1921.15

And while the moral panic about socialism and anarchism in Tulsa eventually abated, the merchants of hysteria—newspaper publishers, oil executives, and local politicians—quickly found a new villain. The Tribune would report on May 29, 1921 that a young black man named “Diamond” Dick Rowland “attacked” a young white woman in a downtown elevator.

The Tulsa press of this era had dedicated itself to flushing out enemies from within. The Socialist Party had been purged, the Allies won the war, and yet inflation continued to show up in the pages of the newspapers. Despite all the fearmongering, violence and predation against those dreaded Others, Tulsans’ grocery bills just kept going up.

“The high cost of living has become an obsolete term,” a Tulsa Tribune reporter noted in May 1920.

“The modern term is outrageous cost of living.”

Editor’s note: This is the first installment in an ongoing series with Oklahoma author and historian Russell Cobb.

Footnotes

- “The Greater Enemy,” Tulsa World, May 8, 1918, p. 4.Return to content at reference 1↩

- See note 33 to Ellsworth’s Death in a Promised Land, p. 124.Return to content at reference 2↩

- A nickname for people affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World.Return to content at reference 3↩

- Ellsworth believes Condon was behind an article titled “Say Laundryman Is Unpatriotic,” which listed the name and address of a business owner who would not buy Liberty Bonds. Such people were harassed and even killed by paramilitary organizations like the Klan or the Knights of Liberty.Return to content at reference 4↩

- Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land, p. 21.Return to content at reference 5↩

- The Home Guard is not to be confused with the National Guard.Return to content at reference 6↩

- These names continue to leave a legacy on the city. McFarlin Library at the University of Tulsa is perhaps TU’s most prominent landmark, while Lewis Avenue is named for S. R. “Buck” Lewis. Return to content at reference 7↩

- The building still stands on Main Street, occupied by The Tavern and Antoinette’s Bakery, among others. Return to content at reference 8↩

- 1910s slang for “vagrants.”Return to content at reference 9↩

- Although the men were taken from police custody, it is widely accepted by historians that the police willingly went along with the plan to torture the men outside of town.Return to content at reference 10↩

- See James C. Foster, The IWW and the Mid-Continent Field (University of Arizona Press, 1982)Return to content at reference 11↩

- Glenn Condon, the managing editor who called for torture and death to anyone supporting the I.W.W., became a genial radio host known as “Mr. Oklahoma News.” He hosted a lively dance party on the airwaves of KVOO from 1:00am to 5:00am called “Oil Club Night” from the 1930s to the 1940s. Condon also served as news director for KRMG during its early years. Return to content at reference 12↩

- See Nigel Anthony Sellers, Oil, Wheat, and Wobblies: The Industrial Workers of the World in Oklahoma, 1905-1930 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), for a complete treatment of the Tulsa Outrage. On p. 233, Sellers names the names of alleged perpetrators, although none ever faced justice for the incident. Return to content at reference 13↩

- This story will be told in a future installment of this series.Return to content at reference 14↩

- What was a wealthy Tulsa newspaperman to do? The new editor and publisher of the Tulsa Tribune, Richard Lloyd Jones, quickly one-upped the World in its xenophobia. It was now “grossly ignorant” Mexicans and Black office-seekers, rather than Wobblies and socialists, that were ruining Tulsa. Jones argued that he believed in equal justice and fairness, but that “elective offices in Tulsa city and county should never be filled by a Negro.”Return to content at reference 15↩