Nealay Patel and Josh New

Josh New Gallery, 2308 E. Admiral Blvd

Until May 31

I didn’t know what to expect from the spring exhibition at Josh New’s The New Gallery, which features the works of jewelry designer Nealay Patel alongside figure photography by New—or even that it would be a dual show. I only knew that it would mark Patel’s gallery debut and a departure from the duplicative craft kits he designs for his jewelry business, SilverSilk & More. I was in for quite a few surprises.

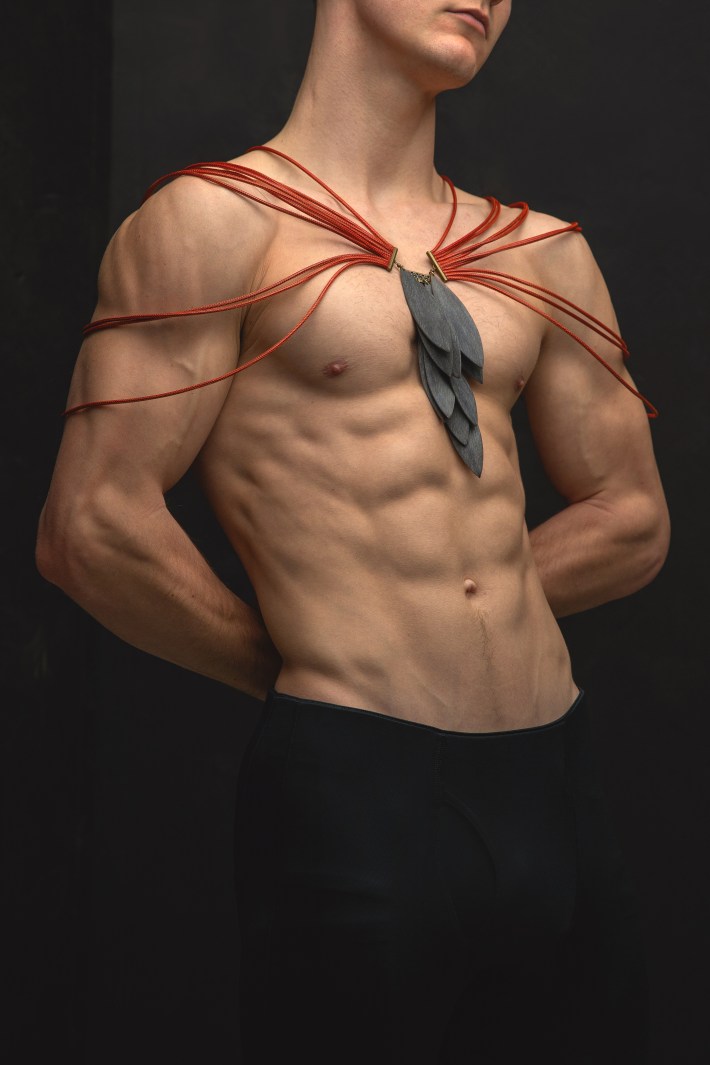

An arresting example of the pair’s collaboration stood just inside the entryway: a mannequin clad in nothing but a beaded chain harness, adjacent to a photographic print of a masculine torso adorned with the same. What followed was a celebration of queer joy and self-expression in defiance of capitalistic constraints—including several jubilant drag performances throughout the evening.

The beads in Patel’s work are made from a unique natural material: Filipino carabao horn. A type of swamp buffalo, carabao are commonly raised as draft animals for cultivating rice paddies. Following their deaths, their horns are often recycled into bone meal, gelatin, dog treats, and beads.

On the entryway mannequin, the beads are polished and set in chain link, almost resembling plastic with their glossy black appearance. Elsewhere in the collection, they bear a raw, matte finish. Emblematic of masculinity and power, the carabao horn complements Patel’s use of other organic media, such as wood and leather, yet contrasts with the delicate texture of his signature knitted-wire chain.

Patel manufactures several versions of the chain, called SilverSilk, at his Midtown home using a machine equipped with six tiny latch-hook needles. These revolving needles stitch hair-thin threads of enameled copper wire into a fine mesh surrounding a ball chain. The result is a sensual, draping silhouette with multi-tonal luster.

Apart from a couple of cuff and cowl designs, harnesses comprise most of the collection. Patel explained that he designed them to fit any body, regardless of size or gender identity. This deliberate gender neutrality distinguishes his collection from most harness accessories on the market. An artifact of leather and kink subculture, the harness is rarely marketed beyond the gender binary in mainstream fashion.

Although harnesses are ubiquitous on Instagram today, they’re a challenge to trace in photographic archives. Researchers at Chicago’s Leather Archives and Museum suggest that they first became fashionable sometime in the early- to mid-’70s. Digging elsewhere, IN Magazine’s Bobby Box identifies hints of their earlier history in post-World War II fetish magazines. Box proposes that U.S. soldiers returning from Japan may have been influenced by kabuki theater’s use of shibari- or kinbaku-style bondage.

By some coincidence, New spent time living in Japan and draws inspiration from kabuki in some of his photos on display. A plan to incorporate byoubu, or Japanese folding screens, into the collection fell through, he later told me via email. But his intent to expose what is often kept concealed did not. Having grown up gay in a strict religious environment in Oklahoma, New says that for him the exhibition represents a reclamation of once-repressed sexuality.

While his portrait, commercial, and editorial photography may be familiar to Tulsans, New brings another side of his work to the fore for this show, one that previously lurked behind a button on his website labeled “Personal Projects.” New has a penchant for photographing men in states of undress and has the technical prowess to capture any body type in its most flattering light. An array of photos throughout the studio shows off this skill. But to simplify form, only one model dons Patel’s designs in New’s photos.

“Josh’s lighting, angles, and editing show my designs in their best format,” Patel told me, referencing two photos depicting the model twirling in an elegant turquoise design. “I expressed to Josh the joy I felt when I wore it in my living room and twirled around. I wanted to see if he could make that feeling come to life in a photo, and he did.”

I knew the feeling well. I’d spun myself dizzy wearing a harness I purchased as I lingered in the empty gallery at the end of the evening after the drag performers and the other guests had filtered out onto the boulevard. I’d gestured at that very same image, euphoric, declaring to New that I saw my own joy reflected in it.

Amid intensifying attacks on the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, these moments of queer joy seem ephemeral at times. But that only makes them more radical, more critical to embrace, more necessary to document—and makes collections such as these more sacred.

The Pickup's reviews are published with support from The Online Journalism Project.