I’d never shot an AR. I barely knew how to use a pistol. I’m more of an everyday carry pepper spray and pocket knife guy than a classic gun toter. However, for a while now, political anxiety has been eating at my stomach, leading to a more general curiosity about firearm ownership.

As a longtime supporter of strict gun laws, it felt strange going into a gun store for the first time. Black rifles lined the counter, alongside “Antifa Hunting License” stickers. I browsed the selection without any idea what I was looking for, riffling through dusty boxes of ammo and faded Osama bin Laden paper targets.

While the staff was nice enough to entertain my base-level questions, I felt out of my depth, and not entirely welcome—the novelty stickers didn’t help. Maybe the staff could smell something on me that was foreign to them, or perhaps they just didn’t care for my Denver Broncos hat. (It’s hard bein’ a "Bo-liever"!) Either way, I decided to look elsewhere for guidance, in the hopes of finding an alternative gun culture to the one I knew.

A growing number of left-leaning folks are reconsidering their attitudes to our nation’s second amendment in the wake of political upheaval, a rise in hateful rhetoric towards LGBTQ+ communities, and even the vigilante actions of Luigi Mangione. Still, for many in queer spaces, firearms conjure images of the 2022 Club Q mass shootings, where Tulsan Daniel Davis Aston died saving someone’s life, and other acts of violence enacted against minority communities. In a nation that refuses to deal seriously with gun control and mass shootings, many advocates believe that what they see as an arms race is just not a solution to end the cycles of violence.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter, The Talegate

However, historically, groups such as the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement have relied heavily on guns to protest oppression and protect their community when they couldn’t trust or rely on higher authority. So, with a growing number of liberal and leftist gun owners, demand for spaces to train and learn has blossomed since the last election. Where there is demand, there is someone willing to fill it, which is how I got into the world of local alternative gun organizations and the people who run them.

While I knew of national groups like the Socialist Rifle Association and the John Brown Club, I wanted to look closer to home. Soon enough, I got in touch with the growing local LGBTQ+ gun community. I quickly found that, just as the LGBTQ+ community isn’t a homogeneous monolith, neither are its gun owners.

My first stop into alternative gun culture was with Mike Abla and Inclusive Defense Training (IDT), who I came across on Instagram. I liked the vibe of their page, but it was their slogan—“Come learn how to be dangerous with us!”—next to their sign-up link that sold me.

While I had a good feeling about the program, I was still a little wary: I’ve been around gun culture in different forms my whole life and have personally seen the toxicity in many of the spaces. Watching any mainstream firearms channel on YouTube will make you want to steer clear of the whole culture. Blatant racism and hatred pointed at the left and the LGBTQ+ community are common, as are surface-level fear tactics used to sell weapons and gear. A part of me was afraid that even an inclusive safety class could end up being the same old paranoia and fear-the-other rhetoric, just with a rainbow flag.

However, I found pretty immediately that Inclusive Defense Training embodied a different type of gun culture, one more accepting and kind. Not long after I signed up, Mike personally reached out to me to see if I needed to borrow anything and ask how I was feeling about the class. Mike answered all my newbie questions, helped me pick a good sidearm, and even helped me shop for a safer holster than what I had. This was a good indication of what IDT was all about: making a safe, non-threatening space for all to learn.

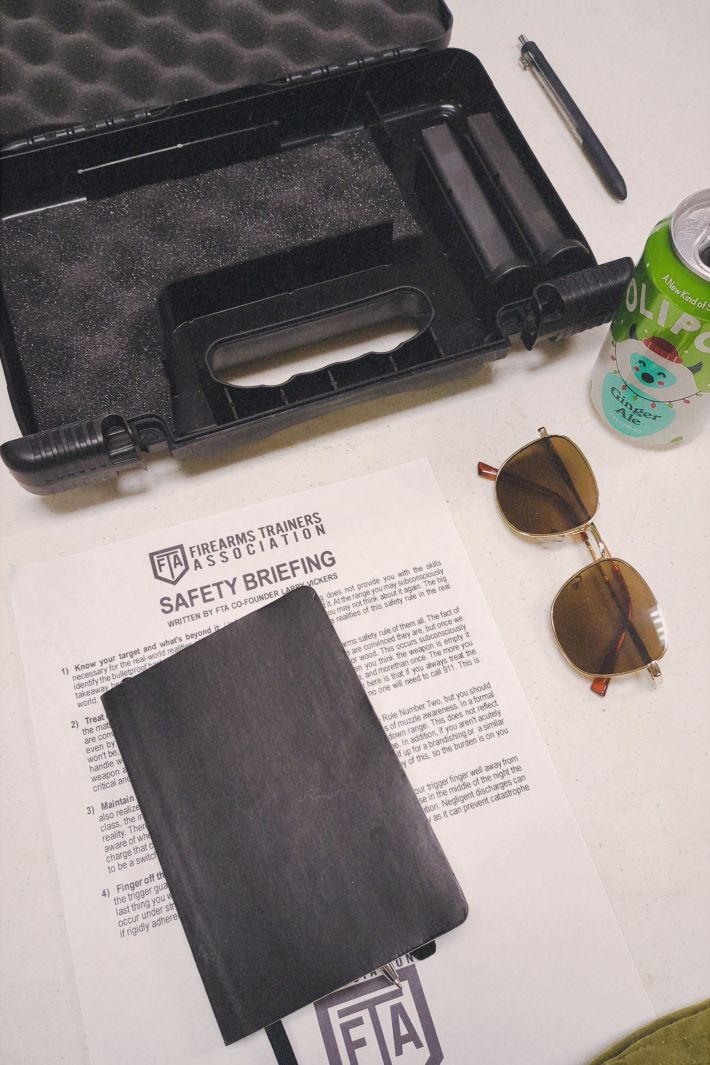

I joined the level one course, meeting up with a diverse gang of fellow trainees, each of us carrying a little hardshell gun case and a snack. However, it would be a while before we even got to open our gun cases (or snacks) as we got to know our instructor and IDT itself.

Mike Abla can’t abide a bully. After a lifetime of being the victim of machismo culture and on the receiving end of violence and threats, he decided it was time to get a little dangerous. “I discovered that most of the bullies I encountered folded if faced with someone who could hurt back,” Mike explained about IDT’s slogan. The retired behavioral health nurse decided to look into defensive shooting classes, and later into instructor classes, but kept running into a particular set of issues. Classes were filled with other white, cisgender males, and instructors often used disparaging language against LGBTQ+ people. “A little research showed that the people who are most likely to suffer a violent criminal assault were the very people who seemed, in my experience, underrepresented in firearms training classes.... It was easy to see a path in front of me to offer a service to my community,” he said. That path led him to start IDT.

We first went around the room and said why we decided to take this training, each of us expressing a similar thought: mainly, the fear of being targeted, and the feeling that traditional classes weren’t exactly inviting. While we each had our reasons for taking this class, all of us had our eyes on one prize: the official IDT patch, a Progress Pride flag with a Glock handgun superimposed over it next to the phrase “DEFEND EQUALITY.” We could obtain this coveted patch by acing the final test: getting three shots on an index card and two on a business card from 10 yards back in eight seconds, a daunting task for a new shooter.

With safety and handling drills done, we were ready for the range. A line of economy hatchbacks with Pride flags and anime characters on their windows followed a Subaru (proudly displaying a bumper sticker reading WWJBD, for What Would John Brown Do?) owned by one of the IDT staff. I shared my ammunition with a fellow attendee, and we encouraged each other as we took turns going through drills. Both of us got noticeably better with each moment of guidance from Mike and each paper plate we sent to the big recycling bin in the sky.

Finally, it was time for the big test. Mike held a timer as I squared up to my targets. He asked me, “Shooter ready?” I affirmed and waited for the beep. The electronic blip sounded, and I drew my pistol and began to fire. First hit, second hit, third hit, all on the index card. I was excited by my success, as I moved to the smaller business card. Too excited, I only got one of the two needed hits, and I took a hair too long: no “DEFEND EQUALITY” patch for me. In fact, only one of the 15 of us would earn it, a first-time shooter who had never picked up a gun before that day. Mike smiled and handed them their patch as they bounced with delight.

I asked Mike if moments like that on the range were why he does what he does. He responded that they were part of it, but ultimately, the real-world applications matter the most to him. Recently, a student of his had to use pepper spray to protect herself and was successful in fending off the perpetrator. “I was happy that her training saved her from going hands-on with the person,” Mike said. “I met with her a couple of days after the incident and gave her a fresh canister of pepper spray.”

After the class, many of us made plans to keep in touch and to return to earn that patch; some free stickers from Mike soothed our wounded pride. It was a strange moment of community, with each of us connecting with someone we likely would not have met otherwise, in a place that not long ago most of us wouldn’t have gone to. With new knowledge and friendship, we all left the range feeling a little more dangerous that day.

Feeling a little more confident in my abilities, I reached out to some local queer gun groups to see if anyone was interested in a range day. Specifically, I expressed that I wanted to shoot an AR for the first time. Two local instructors in the trans community, Natalie and Billie, got back to me. Both are very involved in the organizing and Pride communities so, while I had reached out to them separately, they knew each other, and so we all got on a group chat together to set a date for a little practice and a little fun.

Natalie, a trans US Army veteran, certified instructor and private security guard, runs a group called LGBTPew that is focused on training queer communities in self-defense. The seeds for the group were planted in 2022 at a Pride event she attended the day after the Club Q shooting. “It [had] just happened, and as a result from that, I had a bunch of friends and stuff coming up to me [saying], ‘Hey, you were in the army, right? You know how to shoot? Can you teach me how to shoot a gun?’” Soon after, she started LGBTPew with a philosophy of training first-time shooters in useful community defense skills and helping folks from her community avoid harassment, bad training, and unnecessary equipment purchases.

“Guns are kind of my special interest,” Natalie explained. “I like how the little bits and bobs work together and everything.... The usage for self-defense is just a convenient coincidence.”

Billie, on the other hand, represents a more self-taught, pragmatic and anarchic approach. Billie, a parent and co-founder of Community Pride, has a more utilitarian relationship with firearms, seeing them as a means to an end. “When you see me joke around online about how I don't like guns ... it's that I enjoy the process of learning, and I enjoy what they can do. But I don't care about guns,” said Billie. As opposed to Natalie’s LGBTPew, which is focused on defensive rifle training, Billie teaches one-on-one trainings focused on anarcho-indigenous perspectives, mutual aid, first aid, pepper spray and pistol safety training. While they have different approaches—Natalie coming from a regimented military training, Billie with her self-taught street smarts—they share a common purpose and recently started working together. “We started them [our trainings] separately, and it wasn't until just a few months ago that we started converging paths,” noted Billie.

I met up with Natalie and Billie at the US Shooting Academy, an outdoor range north of Mohawk Park that would be a familiar site to anyone who has worked in law enforcement. A short side road flanked by squad cars and barbed wire gates led way to a wide open area where the range is nestled between police training buildings. We were warmly greeted at the counter by the staff, who quickly set us up with a range bay and targets.

Due to the location and general political climate, I asked Natalie if she’s ever run into issues at this location. She recalled asking the general manager if teaching classes here to queer folks would cause any issues or harassment. The manager told her that the second amendment is for everyone, and if anybody ever gave anyone any shit, to let him know and he would take care of it. This attitude seemed to extend to the staff as well, who were far more interested in geeking out over a particular model of pistol on display than any hot-button culture war issue: yet another example of guns bringing people from very different cultures together.

At the range, we started small, going over safety basics using a vintage small-caliber rifle that once belonged to Natalie’s grandfather. Once I proved I could handle it without pointing it at myself or others, and got some hits down range, it was time for the real thing: Natalie’s very own modern semi-automatic rifle, a classic black and tan AR. A sticker reading “THIS MACHINE MAKES FOLK MUSIC” rubbed against my cheek as I aimed down the sights. CRACK—that classic, satisfying snap sounded crisp through my electronic ear protection. With each exercise, I was getting better hits in less time, and having a blast doing it.

In between range exercises, Natalie and Billie talked about more than just firearms, although there was a heated discussion on Glocks. They also talked about avoiding paranoia, fear of the other, and separatism. To them, the solution to political division, climate change, and economic collapse isn’t some cabin in the woods; it’s building community networks across all divides, outside of the usual capitalism framework. They shared big ideas about starting mutual aids to provide training for de-escalation security teams, medical care, and even storm spotting. “We want to establish a group that is ready and capable of mobilization.... It's really important that we are of the community, and that means that we interact with average normal people,” Billie explained on the importance of not just splitting off from society, but meeting it where it's at and working with it.

Natalie and Billie’s foremost goal is ensuring the safety of trans folk by educating them on proper pistol and rifle skills to increase survivability in worst-case scenarios. They work hard to reclaim an activity that has historically been hostile to people like them, creating a space for all to get access to training and other resources like mental health and even car repair. While their backgrounds, philosophies, methods, and even views on firearms could be very different at times, they made a complementary pair, leading me through various training exercises together with playful banter and useful critiques.

While their approaches differed, they did share their joint dream: an all-trans competition shooting team. The team’s proposed name? “The Attack Helicopters,” said Natalie with a big smile, reclaiming a 2010s-era internet meme originally meant to mock transgender identities.

There’s a growing change in firearms culture, and that change can be felt right here at home. During a snack break at the Inclusive Defense Training class, I sat next to a married couple with matching pistols and asked, “How will you tell yours apart from your wife’s?”—to which she replied, “I’m gonna bedazzle mine!” While a bedazzled weapon may offer no tactical advantage, it speaks to the love, community, and ability to be ourselves that was exemplified in this prefabricated metal shed adorned with vintage NRA signage.

After getting versed in defensive pistol and rifle skills, I felt far better about my ability to protect myself and others. Additionally, I had made friends and connections in a gun culture that I had always felt would want to keep someone like me at arm's length. I found the alternative gun culture I was looking for. More importantly, I found a community that not only cared for each other, but also carried for each other.