“Meat Engine” by Beedallo

Positive Space Tulsa

Through September 27

Body horror, rampant dehumanization, dysphoria, fin-tech in the water supply, cartoonishly and dangerously distorted reality—you know, just things I’m thinking about, given that it’s a day in 2025 that ends in “Y.” Meat Engine, a small but mighty show at Positive Space, gave me a welcome place to process complicated feelings about how it feels to be a human right now.

To say something’s complicated, even dark, isn’t to say it can’t be fun. The artist Beedallo—originally from Los Chavez, New Mexico, and now based in Albuquerque—documents some hard-to-define discomforts here, in nine pieces (all made this year) that have the rare quality of being genuinely unexpected. Their first show in Oklahoma, on view through Saturday, is a trippy mix that made me shudder, laugh, do several double-takes, and break down a few more binaries in my own thinking.

A trained illustrator who cites Moebius, Henry Darger, Genndy Tartakovsky, and Soviet-era animators as influences, Beedallo sets New Mexican folk art traditions alongside industrial dread, Catholic iconography alongside casual black humor, exaggerated forms alongside scientific detail. Their work has appeared on album art for Future Islands, in promotional material for Apple, and in the art magazine Southwest Contemporary, which praised Beedallo’s “campy viscera.”

“I have never felt comfortable in my own skin,” Beedallo writes in their artist statement for Meat Engine. “As I get older, the depersonalization stemming from this discomfort has been easier to achieve. I have begun viewing my being as a machine made of meat. This has been both a freeing and apathetic shift in mindset. I realize that like any other medium, meat can be sculpted and maintained. The distance I feel when I look at myself in the mirror can be mitigated. I may never have a body I feel comfortable in, but with diligence and patience I can tend to a machine.”

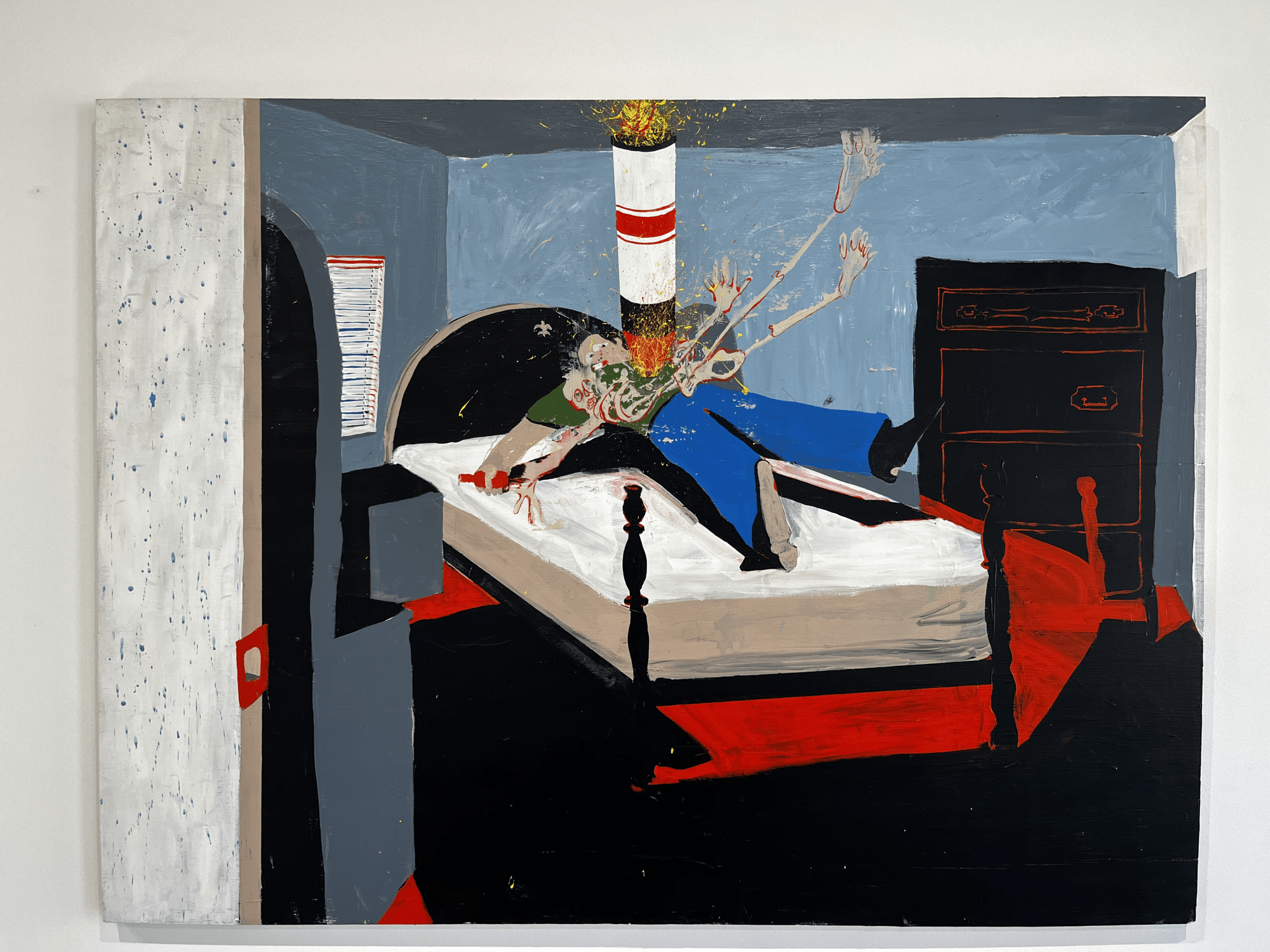

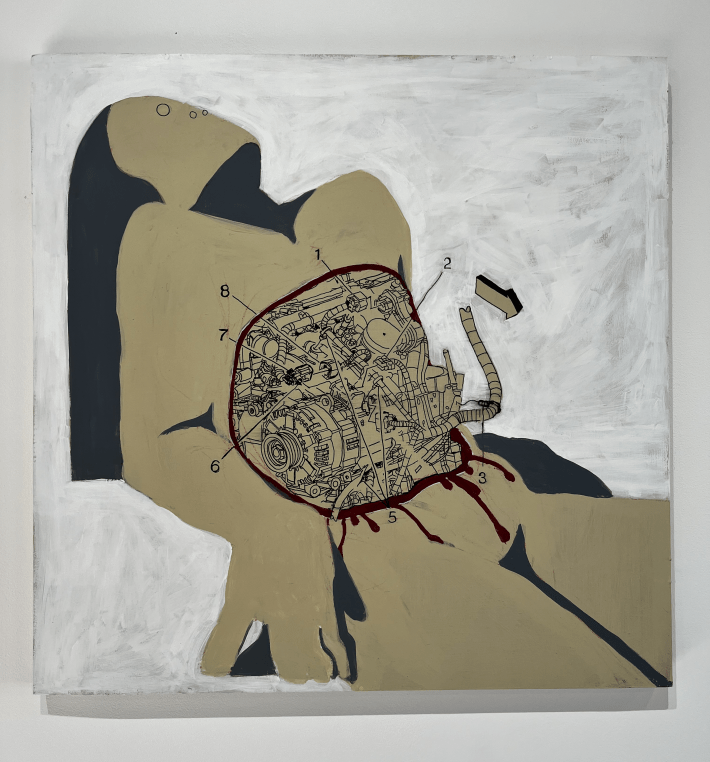

This mode of resigned, almost delighted detachment—part freedom, part apathy—gives these pieces a voice that feels fresh: abstract and political and personal all at once. Beedallo’s bodies are often flattened (sometimes literally, as in the darkly hilarious “Nuclear Fantasy” in which not only a person but also their skeleton and their shadow get blitzed by a bomb in a trim little bed) or shown in bondage, but they’re not objects: there’s flesh here, and feeling too. In “Machine,” a faceless figure arches backwards, exposing guts made of gears, numbered as in an instructional diagram. A little blood seeps out around the cut-out. It made me think of a Patrick Nagel woman for some reason, reclining at home after a long day of modeling in spike heels and shoulder-padded Armani.

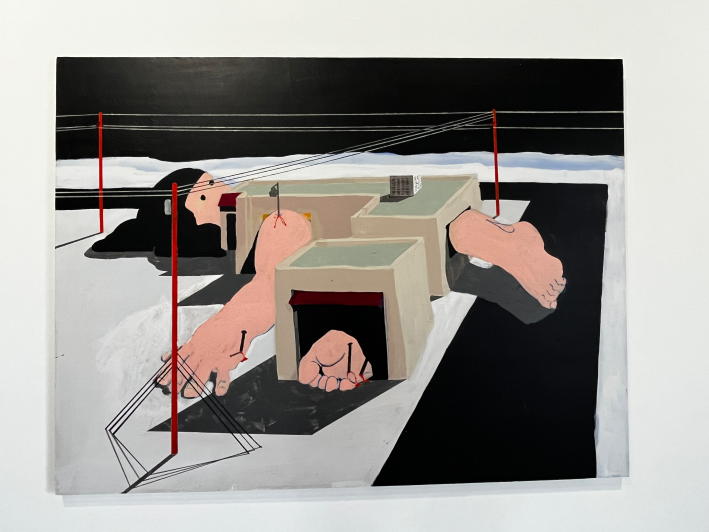

The stark red power line posts and black skies in some paintings suggest an environment that’s not built for humans (i.e., with their wellbeing in mind), but literally built around them. In “This Neighborhood Kinda Sucks,” a nondescript, puke-colored warehouse or segment of strip mall contains the giant, inert, salmon-pink body of what might be a child, whose limbs and head bulge out from the building’s orifices. A lightpost pokes up through their arm, and a rooftop A/C unit sits just level with their button-black eyes. Guy wires and their shadows make a weird non-Euclidean shape on the snow-covered parking lot; even the non-flesh bits of this scene look uncomfortable, yet somehow at rest.

Nearby, in “Holding My Head In My Hands,” a giant barefoot figure does exactly what the Amelia Bedelia-ish title says. Both heads are crowned with nails, and their eyes gaze at each other as they seep and weep drops of blood, framed by cross-shaped telephone poles whose lines squeeze in at sharp angles toward a distant vanishing point.

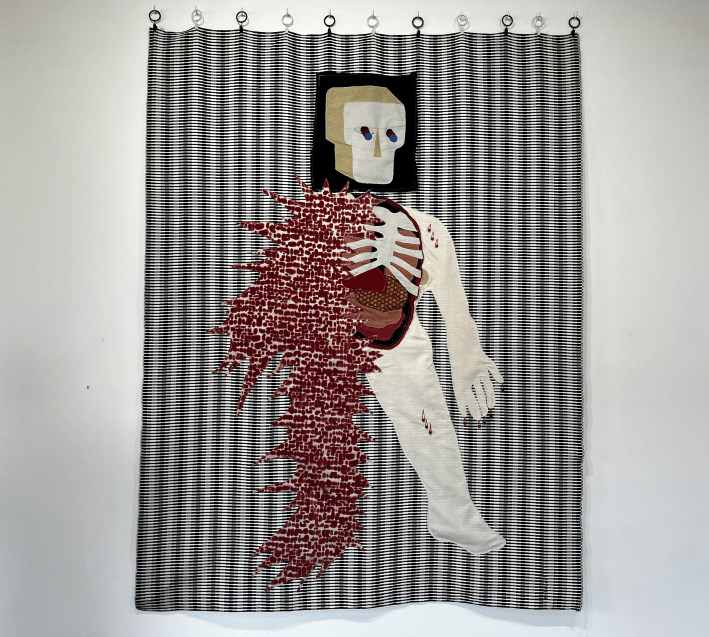

Most of the pieces in Meat Engine are done on wood panel, with materials like acrylic, house paint, graphite, and flashe (a vinyl paint) which Beedallo uses with a sure hand. The two exceptions—“All the Ways You Will Fail Me,” a large piece made with recycled upholstery fabric, and “The Same But Different,” a terrifying rapid-fire video collage from an oral pathology book—are standouts that speak to the range this artist has to explore.

You can extrapolate a political or social statement from this show, or you can just revel in the way Beedallo looks with amused, confused, concerned, and genuine love at all of these figures, textures, materials, and situations. (You can also hear the artist talk about their work at the gallery at 2pm on Saturday.) Machines get used and decay just like bodies do; they both need care and skill and mindful handling. The ultimate meat engine, you could say, is the heart.