Little Shop of Productions: The Just Assassins

Theatre Tulsa Studios

January 17, 2026

While we’re only a few weeks into 2026, Little Shop of Productions just wrapped a third production in its impressive first season: Albert Camus’ 1949 play The Just Assassins. The story is based on the real-life assassination of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, which took place in Russia just after the turn of the 20th century, back when the country was still ruled by Tsars.

A more literal translation of the title would be “The Just” or “The Righteous,” a nod at the main subject of conflict in this work. All five members of the play’s revolutionary squad have given their life to the cause of the Socialist Revolutionary party with the fervent desire to bring justice to Russia, but they all have different ideas of what that looks like in practice.

For some theatregoers, the script might have felt like an extensive overexamination of philosophical questions: When is violence justified? How much are you willing to sacrifice for a cause or an idea? Does ignorance absolve you? Does the end always justify the means? And is there a place for love, for life, in times of terror? But for someone like me, who constructs philosophical debates in my head so I don’t get in trouble in the comment section, it was kind of cathartic to see the back-and-forth externalized, and I was intrigued to see Camus’ answer to each of these questions.

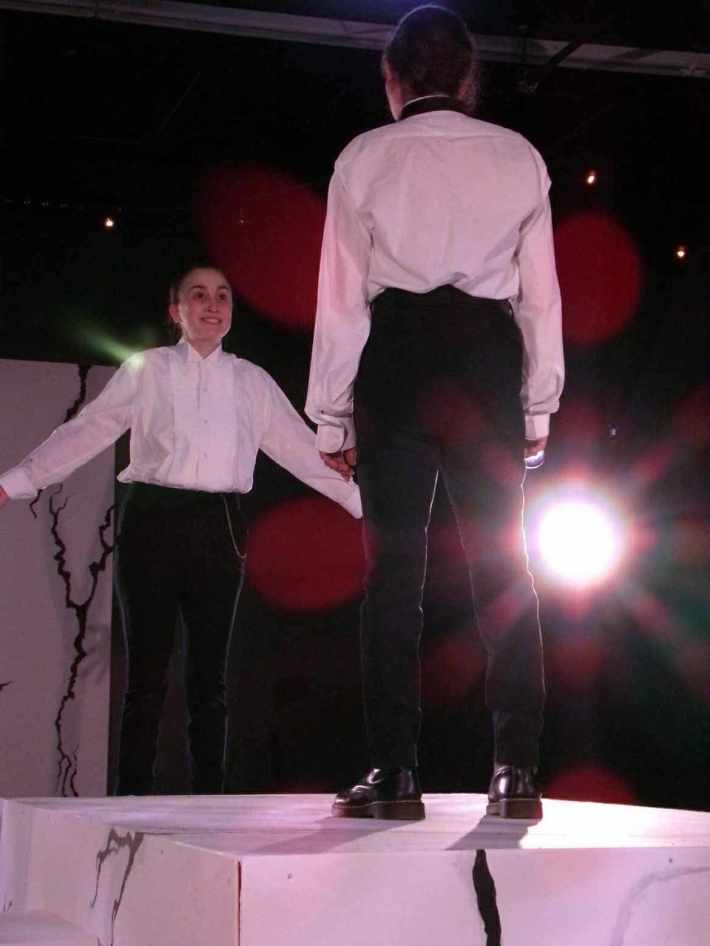

The show’s set helped ground me. The production design of The Just Assassins marked a bold 180-degree swing for Little Shop, with director Anna Seat stripping the show of period specificity and leaning into expressionism to craft a poignant, universal metaphor.

Constructed so that audience members sat on two opposing ends of the stage, the set was almost abstract. Large blocky platforms of different heights and widths created multiple levels. Two small walls, one with a window, were placed on the sides of the stage that didn’t have audience members. All set pieces were coated in white with stark, jagged black cracks, alluding to the immense pressure the group feels to pull off the assassination and how that pressure could be affecting their mental state.

This pressure was present the moment the lights came up on two members of the organization, chemist Dora Doulebov (Emma Dahl) and group leader Boris Annenkov (Rebecca Gray). The actors spoke volumes with their stiff posture and watery eyes; the stakes immediately felt high. This tension dissipated as the three other members of the organization returned to command central: prison escapee Stepan Fedorov (Radar Bishop), former university student Alexis Voinov (Stevie Vineyard), and a poet, Ivan Kaliayev (Levi Gerber), tasked with throwing the first bomb to kill the Grand Duke.

As the five society members discussed their well-thought-out plan for the assassination, I almost forgot that they were planning a murder until someone knocked on the door of their hideaway headquarters. As Boris stepped out to identify the visitor, I was shocked to find myself uneasy. What if the group was caught? What if this was the last we saw of Boris?

These actors, under Seat’s guidance, crafted tangible individuals and a tight collective in a sea of philosophical debate, even if the decision for all actors to speak in a Russian accent kept me at a distance at times (and I wonder if the universality of the play’s message and artistic design would have come across more powerfully without it). Vineyard, whose character is initially tasked with throwing the second bomb at the Grand Duke, made me believe she was having serious second thoughts with her wide eyes, shaky hands, and flittery shuffling around the stage. Bishop brought a hard-to-match energy to Stepan, his indignation commanding the room. While this appropriately made it hard to root for him at first, I found myself softening toward him by the end of the play. Dahl’s gripping performance was a masterclass in delayed gratification. Her bottled emotions simmered until they boiled over at the end of the first act, leaving her in a state of manic, stricken grief by the play's end. When it came time for her final monster of a monologue, I could not and would not look away.

What made this show really stand out to me was the way Seat punctuated the philosophical debate with two visceral moments. At the end of act one, Dora watched out the window and narrated the assassination attempt as Ivan, offstage, threw the bomb at the Grand Duke. The moment was timed with a bright flash of light in the window, a hyperrealistic flare above the audience, and a chest-shaking audio cue that made me jump in my seat. It felt like I was being thrust out of my brain and back into reality: A man was now dead. And despite all that build-up, no one was celebrating.

Ivan is arrested for the assassination and sentenced to death. In the play’s final scene, Stepan describes the hanging to the rest of the assassins. Seat blocked the moment so Ivan and the chief of police (Dawson Lynch) return to the stage onto the highest platform, making it impossible for the audience to look away from Ivan. At the exact moment Stepan described the death, a stomach-churning sound effect of Ivan’s neck snapping cracked through the room and the lights immediately cut out. Ivan’s death reinvigorates the group’s dedication to the cause, so much that Dora requests to throw the next bomb. But her declaration, coming alongside her emotionally devastating monologue, didn’t feel entirely like a victory. It left the audience so stunned that when the show ended, no one left their seats.

Another way the production grounded Camus’ big ideas was by including, at a critical moment, archival and modern-day footage of uprisings across the world. Seat chose period-appropriate film from Russia, as well as video of recent protests from local news stations. With music and smart blocking that built up anticipation, this was a poignant moment in the show, one that reinvigorated Ivan’s dedication to the organization in a moment where he’s tempted to turn on his personal ethics. As an audience member, any lingering confusion dissipated. I got the piece.

Whether these additional artistic elements aligned with Camus’ intended message or not, Little Shop of Productions’ take on The Just Assassins felt like an astute reaction to our current moment. With unrest amplifying across the nation, specifically in Minneapolis this month, it feels like the United States is hurtling toward a situation much like the one I saw at Theatre Tulsa Studios, if it’s not already there. Like many of us, I’ve been thinking a lot about justice lately. Both in my own reflections and with this show, I’m left with the same takeaway: Ideas always bear a human cost, one that affects everyone, no matter your position.