The Pickup is an independent media company doing culture journalism for curious Oklahomans. We write stories for real people, not AI scrapers or search engines. Become a paying subscriber today to read all of our articles, get bonus newsletters and more.

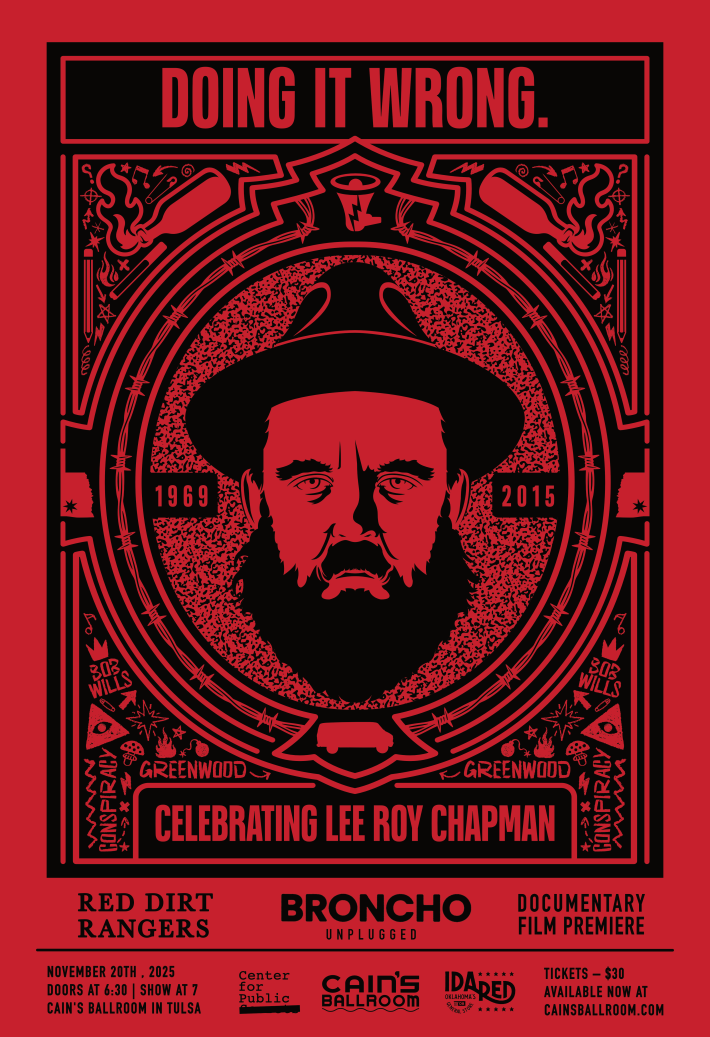

Following up the roundly successful first season of Sterlin Harjo’s latest hit series, The Lowdown, a media-slash-music hootenanny Thursday night at the storied Cain’s Ballroom will celebrate the life and legacy of the real-life inspiration behind the show’s main character: Lee Roy Chapman, the rabble-rousing writer who dug into Tulsa’s history and published exposés that broadly altered the city’s view of itself and — at least if you’re a sign that said “Brady” — literally changed the Tulsa landscape.

The event is titled “You’re Doin’ It Wrong,” which was something of a motto for Chapman. Maybe less a motto, really, than a battle cry. He seemed to wield it as a declaration of punk positioning or outsider status, a critique of established institutions and practices. Then again, if you’re wagging fingers and telling people how to do something “right,” you’re arguing less for nonconformist points of view and more for simply a new kind of establishment — the way you think insiders ought to behave.

This seems to have been a primary complication in Chapman’s life and work. In some ways he was an outsider — publishing journalism without journalism training, researching history without a history degree. One obituary for Chapman labeled him “a self-taught historian” and “a true citizen journalist.” To fully understand this important and impactful but also provocative Tulsa figure, it’s useful to attend to those specific adjectives.

A True Outsider

Calling anyone a “self-taught” anything throws a little shade on their skills and stops them just short of claiming a bona fide credential. A dictionary definition of historian says such a person must be an “expert in or student of history,” providing just the kind of pivot away from sanctioned expertise that Chapman relied on. Many assume that an accredited education and methodological training are a necessary prerequisite to printing “Historian” on a business card. Saying Chapman was “self-taught” denies that — even while it infuses a useful maverick sensibility into the description that Chapman promoted for himself.

The phrase “citizen journalist” is more fluid. A particular education has never been a consistent precondition for reporting just the facts, ma’am, and in my own two-decade career as whatever constitutes an “official” journalist, I worked alongside numerous skilled professionals who lacked mass-comm degrees and mastered the trade on the job, learning by doing. Journalists are not examined for their credentials a la lawyers or doctors, so calling Chapman a “citizen journalist” may be an insult only with the same flavor as “citizen scientist,” which implies someone doing the grunt work helpful to “real” science. Chapman’s obit even makes excuses for him: “While he had no formal training as a journalist, Lee Roy’s depth of knowledge and ability to uncover uncomfortable truths should rank him among the state’s top investigative journalists.”

In the 21st century, though, does a figure like Chapman require the excuses? Rank, credentials, and qualifications seem to have been democratized along with everything else in the digital era — and because of it. Beginning with blogs and followed by social media and podcasting, none of which require supervised training or dues-paying, the traditional gatekeeping role of legacy media and even academic institutions has come off its hinges. Creators, curators, and influencers reach global audiences and intercultural impact without the need of a publishing contract, an editor’s approval, or a university degree. Substack is the new journalism. YouTube is the new ABC.

Doors open for You're Doin' It Wrong: Celebrating Lee Roy Chapman at 6:30pm Thursday, November 20 at Cain's Ballroom. Use the code DOINITWRONG to get $5 off your ticket price at checkout.

While such examples are often cited to support arguments against this evolution, the other side of it posits that voices like Chapman’s likely wouldn’t have been heard in a previous era. The digital content-creator model prioritizes a unique point of view and voice — a distinct and purposeful blurring of the professional and the personal — over adherence to traditional journalism-school norms, like strict objectivity. This still-emerging environment fosters figures like Chapman, whose success stemmed from tenacious, independent archival research, an authentic voice, and a commitment to uncovering those uncomfortable truths, often with little to no corporate or academic backing.

Primarily, what “self-taught” and “citizen” add to the work of history and journalism is a whiff of failure on the part of the institutions that those words modify. The implication is that historians and reporters have slacked off and neglected their real duty, so autodidactic everyfolk are called upon to step up, throw shoulders to abandoned wheels, and right some wrongs.

The innuendo is endemic of a creeping and largely manufactured right-wing ideology that existing social institutions have failed us and deserve the wrecking ball, any wrecking ball.

A desire and need for reliable journalism, however, has not waned in America, only the business model supporting it. So the snake is eating its own tail: if the professional institutions are wrecked, others will rise up to fill the voids. Chapman and upstarts like him, then, aren’t outsiders as much as they are hustlers serving neglected markets and thus making — as a colorful former journalism colleague of mine used to say — chicken salad out of chicken shit.

A Question Of Values

That former colleague is retired Tulsa World writer John Wooley. He has written reams of insightful and important journalism about Western Swing and Red Dirt music — some of which also appeared in This Land and was anthologized alongside Chapman’s work — as well as important books of cultural history (a popular account of the Cain’s Ballroom and Shot in Oklahoma, a chronicle of made-in-Oklahoma movies), none of which were aided by the academic training he received from, say, his undergrad degree in biology.

“Of course, you can learn by doing — a lot of great writers and journalists have — but the question is: Who’s training you?” Wooley asks. “Is it just your audience, the people responding to you? Do you have any mentors, anyone editing and guiding you? Or are you just out there doing it?”

Randy Krehbiel has been an esteemed reporter at the World since 1979, with two books of his own about Tulsa’s great historical reckoning (Tulsa, 1921: Reporting a Massacre and Tulsa, 2021: A Massacre's Centennial and a Nation's Reckoning). “Journalist is a pretty broad title and can include a lot of things,” Krehbiel says. “We’re in the information business, and [Chapman] was in the information business. He was pretty good at it, ‘citizen’ or not. The way I understand it, others kinda helped him form that into a story,” — Chapman often worked with high-quality editors at This Land — “but in the broad sense of the word — of, you know, explaining the world around you, he practiced journalism.”

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter, The Talegate

But which word is more important in the labeling: “citizen” or “journalist”? Is it more important that democracy be served by reporters with licensed training or by information gathered not only from but by the people? The phrase “citizen journalism” is often used to describe user-generated content that acts as a critical resource for emerging nonprofit news outlets, which, being funded by grants and public donations rather than advertising or subscriber revenue, can focus their limited professional staff on high-impact investigative and accountability journalism. Witness the recent launch of the Tulsa Flyer, for instance, which deploys “documenters” gathering hyper-local government data and occasional real-time coverage to pick up the slack left by commercial media’s shrinking resources.

When they have that sort of systemic oversight, such journo-newbies contribute to important coverage. Without it, though — that’s where Wooley draws a line. “I mean, how many citizen dentists are there?” he asks. “Or citizen CPAs? It’s almost pejorative, adding that term. It implies that you’re just some person writing with no oversight or training, and that that’s equivalent to what we [journalists] do, which is not true. It’s like calling yourself a poet when your girlfriend breaks up with you and you write 20 lines of angst. You’re not a poet, you’re just wounded.”1

The open availability of digital publishing platforms is one thing. An alignment — or not — with ideals of objectivity from yesterday’s journalism institutions is quite another. Krehbiel reflects on decades of reporting in which he’s worked hard to remain objective rather than becoming an advocate. Wooley sees a larger move away from this ongoing struggle as a direct social ill.

“The first thing we learned as journalists was to give at least the appearance of objectivity,” Wooley says. “If that sounds quaint in 2025, it’s a reflection of the division we’ve had on the internet, maybe because of it, where anyone can communicate without monitoring and without filters. That’s the main thing that really peels guys like Lee Roy away from the professional pack.”

The piece for which Chapman is most known, “The Nightmare of Dreamland: Tate Brady and the Battle for Greenwood,” which united scattered information and longtime local rumors into a troubling portrait of city founder W. Tate Brady and his participation in the Ku Klux Klan (if not possibly the Tulsa Race Massacre), was not aimed at traditional notions of journalistic objectivity but rather at recovery and accountability. Chapman often promoted his work as the uncovering of the “hidden, neglected and misunderstood” histories of Tulsa. To an ear like Wooley’s, that means “he had an ax to grind.” Krehbiel says Chapman always seemed to be “looking for a way to bring down the high and mighty.” Neither of these views are necessarily journalistic virtues, unless we go back to Finley Peter Dunne’s charge in 1902 that journalism should “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.”

The ideal of journalistic objectivity, though, is somewhat recent. The whole “just the facts” cliché is embedded fairly well into modern culture (I even used it here up above) because it’s been an institutional ideal for some time, recognized by both journalists and their audiences. Scholars like Michael Schudson, a leading critic of journalism history, try to trace the origins of this assumption. Before about 1830, for instance, the notion of objectivity would have confounded most Americans. When I teach histories of news, students are often surprised to learn how wildly partisan colonial newspapers were.2 Notions of objectivity only coalesced much later, based on a belief that Schudson describes as “a faith in ‘facts,’ a distrust of ‘values,’ and a commitment to their segregation.”3 That belief, though, did not emerge solely from institutional goodness. On either side of the Civil War, the role of news-gatherer became increasingly professionalized, and wire services sprang up. If you’re telegraphing your news farther and wider, you sell more of it by aiming for the middle.

The other side of this ideal, though, took shape a century later when objectivity worked at cross-purposes not only to written expression (the New Journalism movement in the 1960s countered strict objectivity in literary extremes from Tom Wolfe to Hunter S. Thompson) but to the deeper investigative inquiry often required within a democracy. Politicians learned to use (read: lie to) the news media, saying what they needed to say in order to maintain objectivity’s both-sides-now balance. This inspired younger journalists to assume more adversarial stances against those in power. They leaned instead into interpretation and analysis of the facts. Into the 1970s, the figure of reporter-as-crusader stepped forward. Had they not, “Watergate” would still mean just a stuffy D.C. hotel.

Ink-stained hands have been wrung about Schudson’s “distrust of values” ever since. Herbert Gans, in a landmark study in 1988 of values in news-media culture, wrote, “Journalists try hard to be objective, but neither they nor anyone else can in the end proceed without values. Furthermore, reality judgments are never altogether divorced from values.”

That could have been a motto for Chapman, too. He readily and unapologetically chose values over impartiality. His goal was to rectify a social injustice and promote a clear, critical position: that Tulsa’s past required a radical re-evaluation. Any lack of traditional journalistic objectivity was a driving and perhaps necessary component of his muckraking style and impact-driven mission.

Who Are You Writing For?

From the historian’s point of view, Chapman’s unschooled practices may be less contentious. He referred to himself as a “history recovery specialist,” a scrounger of artifacts and data with an explicit intent to bring facts to light and create a narrative around them that would lead to community discussion and change. Which it did, scrubbing Brady’s name from theaters, streets, and neighborhoods. A version of this stylish label appears in The Lowdown, one that Ethan Hawke’s TV character flings about proudly and daringly: “truthstorian.”

Brian Hosmer knew Chapman personally and said that they used to talk about these labels. Professor and head of the History department at Oklahoma State University, Hosmer’s a bona fide academic with the lengthy CV to prove it (including impactful books on Native American culture, economics, and policy). “I used to tell Lee Roy when I read his work, ‘Why do you call yourself these catchy things? You’re a historian. You go through archives, you analyze and interpret material, you present a historically based argument. Sounds like a historian to me.’”4

Hosmer himself has coined a phrase for these labors, one flexible enough to encompass both an official academic like himself and a determined participant like Chapman: simply, “history work.” He often explains to students that the work of history occurs in myriad places by people of varying training. Beyond academic historians, “history work” is produced and written by librarians, museum curators, and a lot of podcasters. Hosmer helped produce a podcast at OSU, Good History, which regularly features people crafting historical projects from a wide array of approaches.

The commercial success and public impact of such ventures comes down to audience: Who are you writing for? Most academic fields nurture cultures that, at least by initial necessity, encourage scholars to write for one another rather than to the public. Deans and department chairs have been encouraging professors for ages to engage outside the ivory tower through what’s called “public intellectualism,”5 but free time on a tenure clock is limited at best.

Hosmer says the popular success of David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon irked many academic historians who grumbled that the book didn’t present new information, only combined previous snatches into a ripping narrative. Krehbiel cops to the same notion from his own point of view: “Most of [Chapman’s] stuff on Brady was known, it just hadn’t been put together in quite the way he did. That’s partly my fault, truthfully. I’d written a lot of that stuff about Brady over the years but just never rolled it into one story.”

But Hosmer says that what it came down to for Chapman was not the lack of credentials but ultimately a respect for the very standards of research and truth-telling that such honors originally were enshrined to elevate and secure. Hosmer says he teased Chapman about the distinction, “but believe it or not, his answer came down to respect. He told me more than once, ‘I don’t call myself a historian because I’ve not done the things you’ve done. I’ve not gone through the training or achieved the institutional benchmarks’ that mark someone like me. The point is, he had a high impression of credentials. I considered him a colleague, absolutely.”

Footnotes

- My questions nagged at Wooley, though, and he followed up our interview a day later with more thoughts in an email, including another colorful example: “A ‘citizen journalist’ is a lot like a semi-pro baseball player. He or she has some chops but isn’t really willing to fully commit. Even a semi-pro baseball player, though, has to have some level of skill to compete. As long as a ‘citizen journalist’ has a computer and a keyboard, skill or chops or anything else aren’t necessary qualifications.”Return to content at reference 1↩

- The “party papers” essentially were the Fox vs. MSNBC of their day.Return to content at reference 2↩

- Schudson, Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers, Basic, 1978, p.6Return to content at reference 3↩

- Think Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History podcast, or Jason Steinhauer’s crusade as a “public historian. Even Jon Meacham has become the go-to cable-news pundit for presidential history on the back of a single English Lit degree and some fine storytelling chops.Return to content at reference 4↩

- By writing, well, exactly this kind of op-ed.Return to content at reference 5↩

The Pickup is an independent media company doing culture journalism for curious Oklahomans. We write stories for real people, not AI scrapers or search engines. Become a paying subscriber today to read all of our articles, get bonus newsletters and more.