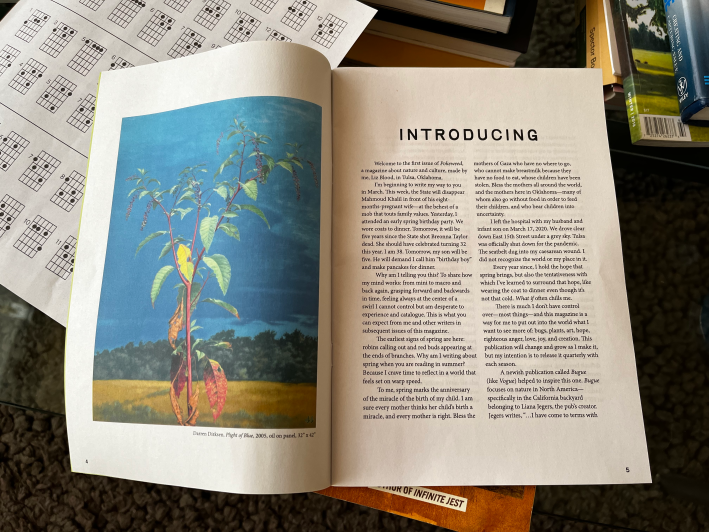

If you’ve heard the word "ecosystem" so often that it’s started to become a meaningless buzzword, have a look at a sweet, sharp, surprising new little magazine called Pokeweed and you’ll get a reminder of what it actually looks like in action.

A lot of what I know about ecosystems—the community kind and the nature kind—is thanks to Liz Blood. She empowered so many local writers, including me and many other Pickup contributors, when she edited The Tulsa Voice; she’s curated art shows in spots like the Tulsa Artist Fellowship Flagship and a half bathroom in her house; she’s been the writers assistant on Reservation Dogs and a writer for The Lowdown; she’s revived the legacy outdoor brand Okiebug; and she’s brought to life a Creative Field Guide to Northeastern Oklahoma that you’re very likely to see in the grubby hands of more than one generation of kids.

Northeastern Oklahoma had a robust and widespread prairie ecosystem not that long ago. Prairies are diverse, sustainable, mutually beneficial. They carry a history that lives deep in the soil. Far from going stale, that lineage sprouts new life every year. Prairies thrive on heterogeneity; uniformity is death. (I could go on, but this National Park Service page gives a solid overview.)

I’m a big fan of a “prairie” approach to pretty much everything: ideas, relationships, art, media, life in general. More voices, more stories, more reading, more connecting through the ecosystem of our shared life—a prairie-informed practice makes life better for everyone. If you’re looking for a particularly lively patch of local cultural prairie to hang out in, grab the first issue of Pokeweed (published by the delightfully named Anti-Pesticide Press), which features a diverse range of pieces by Becky Carman, Darren Dirksen, John Keats, Ken Pomeroy, and other human and non-human creators.

Liz is one of Tulsa’s best practitioners of this prairie way of doing things. The homemade cherry limeades, the giant pokeweed floral arrangement, and the excellent people at Pokeweed’s recent launch party at Tina's confirmed the excellent vibes even before I opened up the magazine. I emailed Liz to ask “why Pokeweed, and why pokeweed, and why now?”

The Pickup: Why did you want to start a magazine, specifically a print magazine?

Liz Blood: I missed writing to Oklahomans. I love print and print layout (or, design). And I prefer to hold what I've written or am reading in my hand. I have trouble doing either on a screen; it pains me. I am an elder millenial, after all. I also think other people like to hold something made by someone else. It's an experience that feels personal. We are meeting through this thing, which you can now carry with you into your life.

The Pickup: What is it about pokeweed that struck you so strongly that you wanted to name this new creation after it?

Liz Blood: Pokeweed the plant is beautiful, hardy, adaptive, and unfairly maligned—like many other so-called weeds, bugs, and people and ideas. Mostly the plant is maligned for being toxic, though its berries nourish plenty of birds and its leaves can be eaten by humans given the right circumstances. Pokeweed is a metaphor: just because you feel threatened doesn't mean something doesn't belong. Just because something doesn't provide an immediate or immediately obvious use to you—that also doesn't mean it doesn't belong. Public support and funding for the arts continues to decline. Insect populations continue to decline. I don't think they're exactly correlated but I also don't think they're exactly not. I used to work in fundraising in the arts. I was always told "art is a hard sell because it's a luxury." I disagree. Art is a necessity, just as bugs are. Without them, what do we have? Pokeweed is an effort towards saving what can be saved and reclaiming the rightful places of things like bugs and braided prairie streams and mammatus clouds and coyotes and art and thought and poetry in our world.

The Pickup: What kinds of things do you hope to publish in Pokeweed?

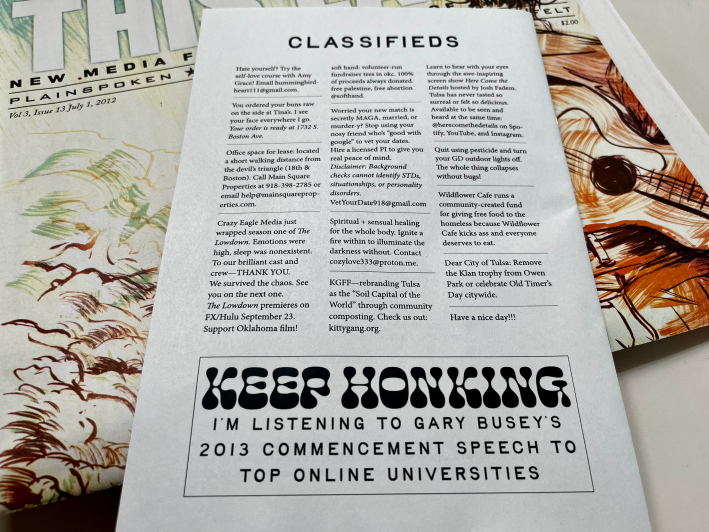

Liz Blood: Pokeweed publishes writing about nature and culture—where those two overlap and intersect and how they talk to each other. This includes essays, stories, odes, laments, provocations, poems, satires, snippets, remembrances, interviews, et al. We also publish visual art, including photography. And on the back, classifieds and a bumper sticker.

The Pickup: You’ve been on a curatorial journey around nature and art the past few years—with the Creative Field Guide to Northeastern Oklahoma, the Sunodos exhibit, and now Pokeweed. What are you learning about what we have to learn through nature, through art, through these community explorations?

Liz Blood: Art asks questions, nature's got the answers, and being in communion with these things—and each other—is how we get through. And remembering that we are not apart from nature. And having fun.

The Pickup: Can you talk about the decision to have classifieds on the back?

Liz Blood: It was just fun! I miss ads sans logos and images and all the extra noise. Tell me what you have to tell me in 15-45ish words and let's tell everyone else. I also miss anonymous rants, missed connections, and the like, which are also published in the classifieds section.

The Pickup: I really want to know more about this Gary Busey commencement speech….

Liz Blood: As far as I can tell, you can't actually find the commencement speech he gave to "top online universities" anywhere online. It appears it used to exist on his vlog channel ... which also no longer exists. I put that on a bumper sticker because I love the idea of A) him giving a commencement address to anyone (can you imagine), B) you can't actually listen to it, and C) everyone with road rage needs to calm TF down and maybe do as he purportedly advised: "pop pills and wander out into the desert until it turns into a Salvador Dali painting."

The Pickup: Where can folks get a copy of Pokeweed?

Liz Blood: Currently, in the Okiebug booth inside of Meadow Gold Mack (1306 E. 11th St.). Follow Pokeweed on instagram at @pokeweedmag for updates.