Editor’s Note: This is the second part of a series by historian Russell Cobb we’re calling “Nasty Newspapers.” It’s named that because a century ago, the magnates who owned Tulsa newspapers had a certain propensity for publishing smears and propaganda as they jockeyed for control over power, the oil patch and city infrastructure. But this story didn’t end in the 1920s: you can hear its echoes in the “America First” propaganda and civil liberties infringements happening today. The first installment of Nasty Newspapers can be read here.

Joe Sring worked the night shift at the Katy Flyer Restaurant, serving bleary passengers from the Katy Depot down the street. Bullets often flew around North Main St., so Sring probably didn’t think much about the white man packing a revolver on his hip at the lunch counter on March 23, 1918.

The armed man watched Sring move about the restaurant. His name was S.L. Miller and he was part of the Tulsa Council of Defense, a paramilitary group mustered by a self-appointed “Committee of 100” that had come to rule Tulsa.1 Miller surveilled people the Committee considered foreign agitators from Germany and anarchists. There weren’t many of those around, so the Council looked for others they deemed unpatriotic. Tulsans who didn’t buy war bonds, Blacks demanding racial equality, union sympathizers demanding higher pay in the oilfields, Mennonite farmers: all were now under suspicion.

Joe Sring thought the good citizens of Tulsa had lost their minds. “Those boys over there are getting what they deserve,” Sring reportedly said. “They don’t know what they are fighting for.”

Miller had heard enough. “What do you mean?” he said to Sring. “I’ve got a boy in the draft.”

“They ought to get blowed up,” Sring said.

That, at least, was Miller’s account of Sring’s last words. No one will ever know what Sring actually said because Miller fired three or four shots into Sring’s body at point-blank range.

Sring’s body fell onto the lunch counter of the Katy Restaurant, and Miller walked outside into a breezy evening, where he handed another police officer his weapon and three shell casings.

***

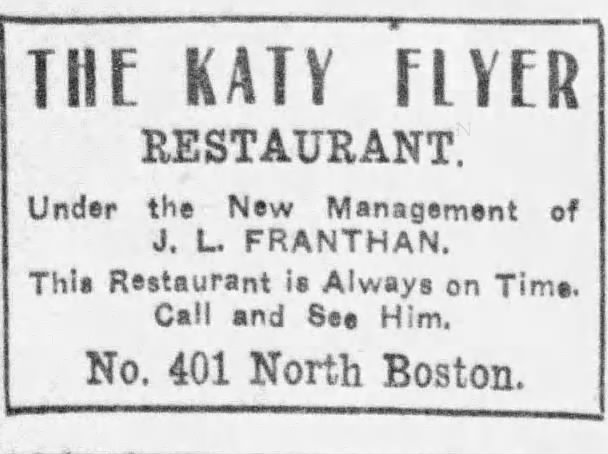

Tulsa first proclaimed itself to be the Oil Capital of the World in 1916. The president of the Chamber of Commerce said there were more millionaires in Tulsa than any city in the nation. It was a peaceful place with nice parks and a flourishing streetcar system! “The richest city in the world, per capita,” he wrote in an ad that got distributed as a news article across the country. “How easy it is to procure a home ... where gold lays in its avenues.”2

Joe Sring had seen newcomers stranded, many ending up homeless on First Street, which was chock-full of houses of ill fame whose businesses were protected by corrupt cops. Hotels served moonshine and roadhouses like the Bucket of Blood catered to every sort of vice.

An advocate for the homeless said newcomers to Tulsa “do not realize the acuteness of the housing shortage.”3 Wages in the oilfields never seemed to match expectations. Exchange National Bank, the “oil bank of America,” could not find accommodations for its own employees.4 The same Chamber of Commerce president who touted Tulsa as the city whose avenues were laid with gold soon ordered an embargo of household goods being shipped into Tulsa. There was simply nowhere to put them.5

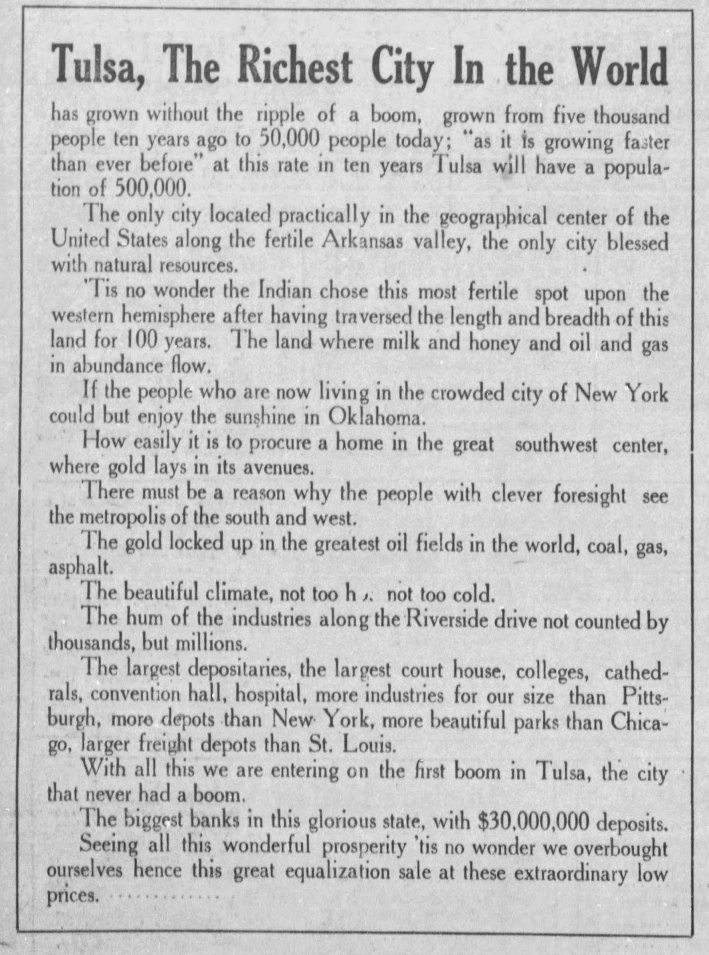

The result was labor unrest and an unprecedented vote share for the Socialist Party. The Industrial Workers of the World welcomed new recruits for a union that sought to overturn the capitalist order. Down the block from the Katy Restaurant, the headquarters for the I.W.W. operated out of the New Fox Hotel. Wobblies6 played cards, traded gossip and sang about the destruction of capitalism:

Would you have freedom from wage slavery,

Then join in the grand Industrial band

Wobblies put up posters of the “sabo-tabby cat” around town, warning oil barons that “bum work” awaited the corporate fat cats who didn’t do right by their employees. As we saw in the first installment of Nasty Newspapers, Tulsa city leaders responded to the I.W.W. by creating a vigilante organization called the Knights of Liberty, which meted out punishment with whips, knives, and lead pipes. The Tulsa World did not mince words when it came to people like Joe Sring and the Wobblies: “Kill ‘em as you would any other kind of snake.” 7

Let’s also remember that the World had earlier spread fake news about the bombing of an oil executive’s house in Tulsa, and that its editors then helped organize and glorify a horrific torture session of 17 suspected members of the I.W.W. This was the Tulsa Outrage, which the World deemed a coming out party for the modern Ku Klux Klan.8

Then came the murder of Joe Sring, an act of patriotism in the eyes of the Tulsa World. Sring had violated the unwritten law of America First.9 America First, then as now, was not really a foreign policy: it was a culture war. There was nothing hidden about its aims: secure white supremacy and defend American capitalism by violent means if necessary.10 Eugene Lorton’s editorials in the Tulsa World were unambiguous on this point. Wobblies deserved death. Blacks could hope for a better future through segregation, but to the Black man demanding equality, “most emphatically he cannot command it as his racial right.”11 12

Sring’s story has been almost completely erased from the historical record, but at the time it set the entire city on edge. The day after the killing, a group of railway workers got into an argument at a boarding house about the war in Europe. One of them, Steve Ivanoff, was originally from Bulgaria, a nation that had been pulled into an alliance with the Central Powers, led by Germany.

At the time, many Bulgarians worked in the Hickory Coal Mines, near the modern-day University of Tulsa campus. Then, as now, immigrants did the low-wage, dirty labor most U.S. citizens turned down. Most kept their heads down, but Ivanoff spoke up, saying that the killing of Joe Sring was a disgrace and the United States had no business in the war.

A Tulsa Police officer named Joe Mains was dispatched after the owner of the boarding house called in a report of seditious commentary. Mains found Ivanoff walking back to work down the Katy railway tracks. Someone fired a shot. An agent from the Council of Defense showed up on the scene. These two men ran after Ivanoff. Mains shot him twice, once in the head and once in the groin.

Within 24 hours, two Tulsa men had been gunned down for expressing an opinion deemed unpatriotic. To the Tulsa World, this was the new reality of President Wilson’s “America First.” The slogan was no longer about keeping America out of war; it was about taking the fight to the enemies within. The killings tested a “new unwritten law that makes it justifiable to slay one who speaks out against his country.”13

The time had come to test that unwritten law in the courts of Oklahoma.

***

At trial, the Tulsa Council of Defense’s S.L. Miller told District Judge Lee Daniel that he had purposely drawn Sring into talk about the war. He wanted to test the waiter, to see if the rumors of unpatriotic talk were true. Sring’s remark that “they ought to get blowed up” had done it. It also appeared that Sring had reached under the counter for something—maybe a weapon?

Judge Daniel wasn’t interested in a possible self-defense angle because the real crime was Sring’s disloyalty to his country. And for that, Miller was justified in shooting him. “[Miller’s] act is what every loyal American would have been forced to do by the blood in his veins,” Daniel said.14

If anyone had committed a crime at the Katy Flyer Restaurant, Daniel continued, it was Joe Sring. What he had said was “the most damnably reprehensible” thing a man could say during wartime. The waiter was a German sympathizer and “a menace … who deserved his fate.”

The courtroom erupted in cheers as Miller left a free man.

A week later, the scene was repeated as Judge Daniel considered the killing of Steve Ivanoff. Officer Mains claimed he shot the Bulgarian in self-defense, but presented no evidence to back up the statement that Ivanoff had a weapon.

A Tulsa Tribune reporter noted that even if self-defense could not be proven, it was clear that “Ivanoff had slurred and made unpatriotic remarks concerning the United States in the war.” 15

The courtroom was packed with members of the Tulsa Council of Defense, the Knights of Liberty, as well as a new organization in town, the Ku Klux Klan. When Judge Daniel exonerated Officer Mains, they applauded. Miller and Mains became local heroes. Miller became a long-serving police chief in Sand Springs. Mains ran for Tulsa sheriff in 1922. 16 The killing of unarmed civilians had turned out to be a resumè booster.

***

All of this must have hit Charles Krieger hard. As we’ll remember from the first installment of Nasty Newspapers, Krieger had been languishing in a Tulsa jail for allegedly bombing oilman J. Edgar Pew’s house in 1917. Sring and Ivanoff were working men with unpopular opinions. Krieger was an actual card-carrying Wobbly who sang radical folk songs and preached sabotage against the oil industry. If working stiffs could be gunned down for their speech, what would stop Pew’s men from lynching Krieger?

Fortunately for Krieger, his plight caught the attention of a group called the Workers’ Defense Fund in New York. The celebrity socialist leader and feminist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn helped organize a small band of eccentrics to travel to Tulsa to work the case.

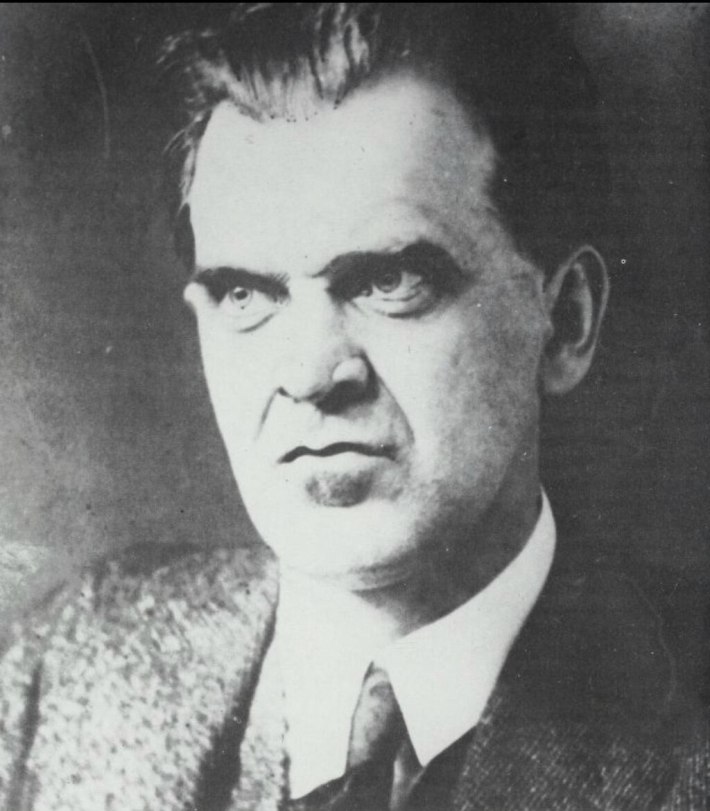

This group must have looked like something out of a Coen brothers noir, equal parts legal thriller and farce. First came the attorney, Fred H. Moore, a classic hardboiled antihero. The scowling Moore wore a wide-brimmed hat pulled down to his brow, cowboy boots and a pistol. He was a legal genius prone to bouts of mania where he would disappear for weeks on end. It was said he had a nasty cocaine habit. He would berate his own witnesses on the stand and many clients—including the famous Italian anarchist Nicola Sacco—regretted hiring him.

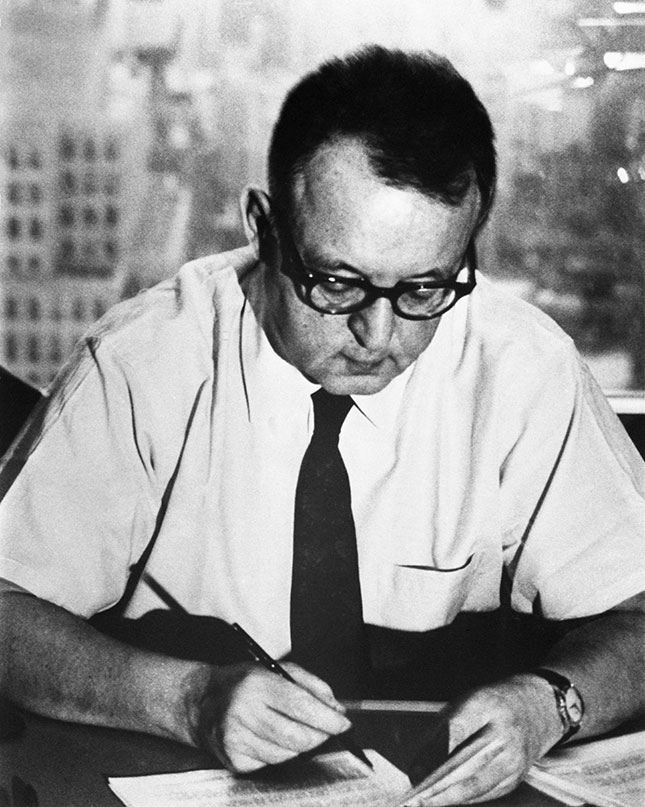

Then came Eugene Lyons, whom Moore met at a train station in Kansas City. Lyons was a poverty-stricken Jewish immigrant who had served in World War I and become committed to international socialism. By his own account, Lyons was a frail and disheveled man who lacked anything resembling physical courage. Lyons’ journalism, though, burned with indignation at the greed, racism, and violence of post-war xenophobia. Beneath his feeble visage was a fierce determination to get to the truth.

Fred Moore could not hide his disgust at Lyons’ appearance. “I thought Gurley was sending us a man,” he said.

This odd couple was joined by a Canadian schoolmarm-turned-socialist orator named Caroline Lowe, whom Lyons described as “a sweet, spinsterish lady driven by social conscience.”17 In Tulsa, a poor Jewish lawyer named George Bonstein lent his services to the defense, risking his life and reputation.

Lyons felt that the whole crew could have been gunned down at any moment. They constantly received death threats, often while coming out of the courtroom. But Lyons noticed something odd during the trial. Men with guns on their hips seemed to enter and observe the scene and then leave without any interference from law enforcement. He wasn’t sure if they were there to threaten or protect Krieger.18

Standard Oil—which held heavy sway over all affairs in Tulsa, especially those concerning oilmen—was frustrated with the district attorney’s failure to make the bombing charges stick against a Wobbly. The company brought in an attorney named Flint Moss who claimed that there had been a sinister conspiracy led by Krieger, in which he had contracted with three notorious outlaws to carry out the crime.19 Moss produced a witness who admitted to stealing dynamite from a quarry in Sand Springs and placing it under Pew’s porch at the behest of Krieger, who wanted the oilman dead.20 Things were looking bad for Krieger.

During the trial, the Tulsa World turned over a column to another oil company attorney named L.G. Owen: “The I.W.W. [is] against our form of government. They have no sympathy for us, they are opposed to any form of capitalism and they believe any taxpayer [is] a capitalist.”21

If unpatriotic speech was enough to justify the killings of Sring and Ivanoff, surely it would be enough to lock away an unrepentant Wobbly in prison. It was a smart strategy to emphasize Krieger’s political sympathies, because the prosecution’s case was otherwise thin.

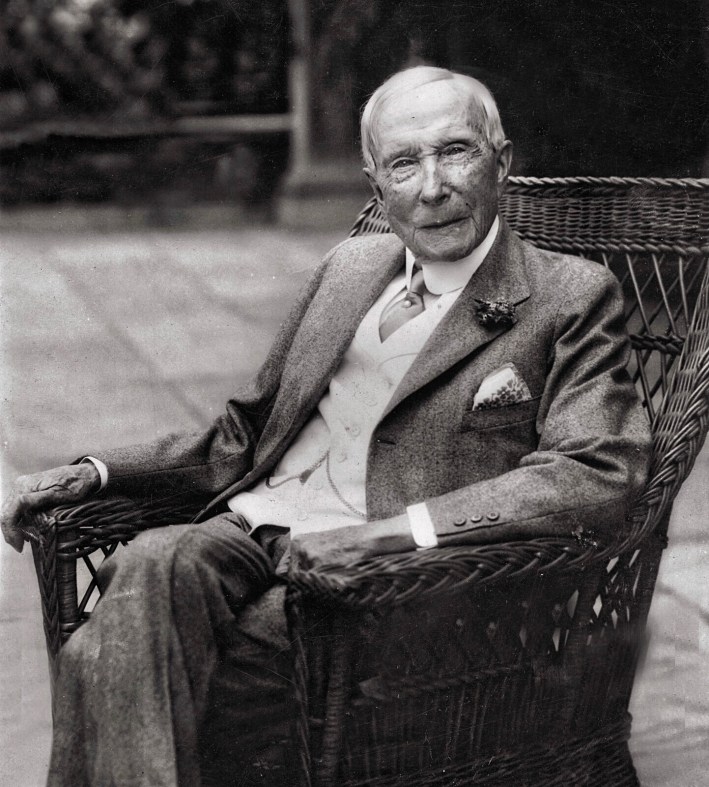

The truth was that Standard Oil’s interest in Krieger’s case was much greater than meets the eye. Most of the “independent” oil companies operating in Tulsa were not really independent at all.22 The controlling interest in Pew’s company was held by none other than Standard Oil founder John D. Rockefeller, the world’s richest man, who by that time was becoming decrepit and loathed. Rockefeller observed a strict Baptist doctrine and had an all-powerful fear of death. He had no charm or rizz to speak of, only reams and reams of money, which he deployed on a mission to establish universities, charities, and nonprofits to improve his image. He looked like a desiccated Jeff Bezos. 23

Among the Tulsans with a dim view of Rockefeller was Oklahoma District Judge Redmond S. Cole, the man in charge of the Krieger trial. Cole was no bleeding heart liberal, but he too resented Standard Oil attorney Flint Moss’s imperious attitude toward the justice system.24

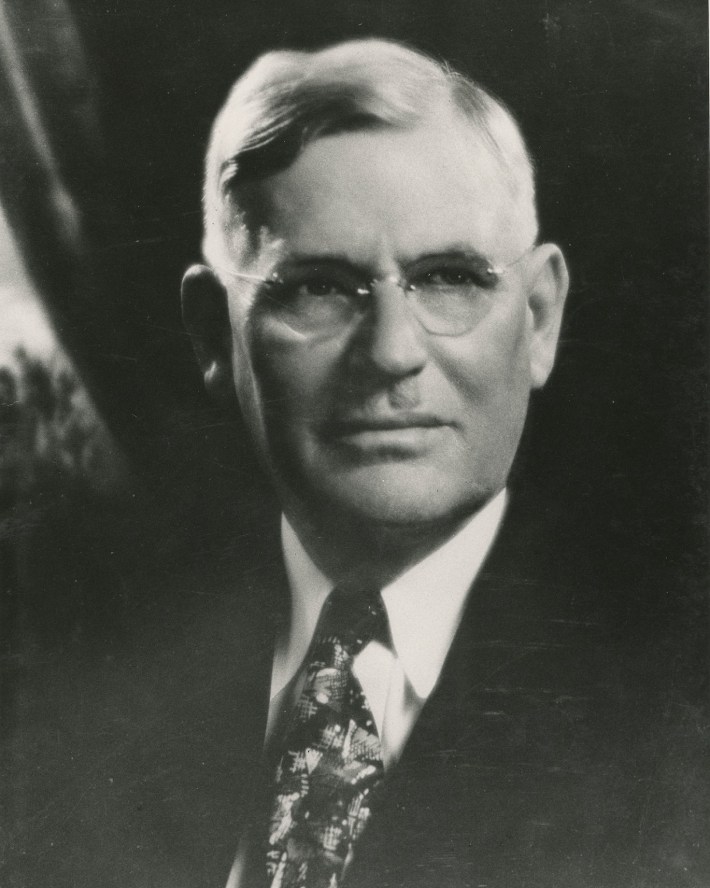

But the biggest Rockefeller hater was probably Charles “Daddy” Page, who was his opposite in every way. Rockefeller was frail and reserved; Page’s corpulent body was in constant movement from the courthouse to the oilfields to his famous widows and orphans colony. Rockefeller established the University of Chicago; Page dropped out of school around the eighth grade. Rockefeller was a teetotaller who shunned human contact; Page, well, it’s hard to find a photo of him in the Widows Colony in which he is not holding several women and girls close to him, some by the shoulder, some by the waist. He had a lusty appetite and a taste for bootlegged whiskey. He smoked old cigar stogies and was happiest while petting his German Shepherd, Jim.

Page posted bail for Krieger and secretly ordered a security detail for him and the civil liberties gang from New York. Meanwhile, in the courthouse, things were falling apart for the prosecution. Two members of the dynamite trio contradicted each other about their meetings with Krieger. The ringleader of the trio, John Hall, was serving time in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

Caroline Lowe—the “sweet spinstress”—went to Leavenworth to talk to Hall and returned to Tulsa with a gleam in her eye. Hall was a terse, hardboiled criminal who had served many years in prison. But Lowe believed he would not lie in court. The Workers Defense Fund attorney called Hall to the witness stand on November 3, 1919. The other alleged conspirators trembled when Hall entered; they had taken plea deals with the state in exchange for testifying against Krieger.

Hall confirmed that the trio had stolen dynamite, but they had no plan to use it on Pew's house. He had crossed paths with Krieger in a Muskogee jail, but the two never conspired about anything. Hall and another man exchanged letters in prison, but none of them ever mentioned Krieger, Wobblies, or anything to do with bombing the house of an oilman. The real bombshell came when Hall revealed that J. Edgar Pew had visited him in prison and attempted to buy his testimony against Krieger. “Pew said he would put me on easy street for the rest of my life,” Hall said.25

There was simply no material evidence connecting Krieger to the destruction of J. Edgar Pew’s house. By now it had become clear that Krieger was on trial for expressing a political opinion. He took the witness stand to defend his association with the I.W.W. Yes, he was a member of the union, and had taken part in a strike in Humboldt, Arizona. But he believed only in peaceful protest. No one could prove that Krieger participated in violent acts in Tulsa or elsewhere.

The jurors could not reach a verdict. This was a town where unpatriotic speech could get you a bullet in the stomach, but jurors seemed to balk at convicting Krieger. Judge Cole declared a mistrial and sent Krieger back to jail.

***

Watching the trial unfold with a keen eye was Charles Page, the Sand Springs oil baron and philanthropist, described by Lyons as a “picturesque 300 pound dictator.” Page wasn’t satisfied running Sand Springs and had come up with a scheme to control all of Tulsa’s vital services, including railways, water, power, and housing. The World’s Eugene Lorton was on a mission to expose Page as a “porch climber.”

“A greater fraud never lived than Charles Page,” the World declared on its front page of June 12, 1917. 26

Page had no sympathies with international socialism, but an enemy of Eugene Lorton was a friend to Charles Page. His paper, the Tulsa Democrat, put up the money to bail Krieger out once again, and Krieger’s legal team visited his mansion in Sand Springs.

Page pulled them all into a walk-in refrigerator and sat on a butcher’s block. He boasted that his men “were all around the courtroom with their fingers on the trigger. The Standard Oil bastards knew that if anyone let loose, there’d be hell to pay.”

The gunmen Lyons had seen around the courthouse were part of Page’s militia. Lyons felt like he was going to congeal into an ice cube as Page held forth, seemingly oblivious to the cold.

“Yeh,” Page said. “I’m respected in these parts, I am.”27

Krieger waited six months for another trial in 1920. In the meantime, Eugene Lyons kicked around Tulsa, wanting to “investigate the state of mind of the community.” The young socialist visited a popular preacher at a local church, “a bulky, red-faced cowpuncher,” who grabbed Lyons by the shoulder. “I have only one piece of advice for you,” he said. “Take the next train out of town, or we’ll hang your hide on a fence!”28

Lyons had seen enough. He left Tulsa before the second trial began, filing a lengthy article about the city and what he called “a clowning of justice” in the prosecution of Charles Krieger.

At Krieger’s second trial, the conspiracy theory collapsed.29 Nearly three years after the bombing, Krieger was acquitted on all charges. The lanky Wobbly took a train home to Pennsylvania, where he worked quietly as a plumber for the rest of his life. Krieger had escaped Tulsa with his hide still attached to his back.

No one was ever convicted of the attempted murder of J. Edgar Pew and his family, adding this crime to a long list of unsolved Tulsa mysteries.

***

Charles Krieger and his team had bucked a dangerous precedent set by the killings of Joe Sring and Steve Ivanoff. Krieger, Judge Cole, and a few brave citizens had managed to uphold the rule of law in a climate that called for blood and censorship. But Krieger’s victory did not herald a return to democratic norms and a respect for free speech in Tulsa. It was now 1920, and editors like Lorton and Richard Lloyd Jones realized that the paranoid style of American politics sold newspapers like hotcakes.

Both editors continued to publish inflammatory articles about “attacks” by African-Americans on innocent white folks, but it was the Tribune’s infamous “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator” that finally lit a match that started the great conflagration of 1921.

In the aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre, the Klan infiltrated all aspects of city and state government. It dispatched agents to conduct public floggings, kidnappings, and beatings of anyone suspected of immoral behavior, race-mixing, or general un-American activity. Thousands of innocent Oklahomans were caught up in mob violence orchestrated by the Knights of Liberty, the Council of Defense, and the Ku Klux Klan from 1917 to 1923. Archival files on the victims take up many boxes in the Western History Collection at the University of Oklahoma.

I’ve perused these files with a mix of outrage and fascination. Everyday citizens were snatched off the streets of Tulsa after 1921 by the Klan. The victims were whipped, tar and feathered, or mutilated. Their punishment was justified by their identities. They were Jews, Catholics, and Blacks who had some involvement in a business deal gone bad, the liquor trade, or had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

A century later, there is talk in all quarters of an unprecedented American tyranny under Donald Trump. But there is a precedent, right here in the Oil Capital of the World. From 1917 to 1923, Tulsans participated in state-sponsored violence and the legal system failed the most vulnerable. Then, as now, many people preferred to look away, or to choose to believe that the victims have done something to deserve their fates.

***

A few weeks ago, I went looking for the grave of Joe Sring at Oaklawn Cemetery. It was supposed to be in the southeast quadrant, a stone’s throw from the Wildflower Cafe. It was Memorial Day, and fresh American flags were planted at veterans’ headstones. I stepped in some mud near the grave of Tate Brady, who at one time had been a member of the Council of Defense and the Klan.

I paced up and down, unable to find a grave for Sring. Maybe weeds had devoured the headstone. A storm blew in, so I jumped back in my car as thunder rolled. The 1921 mass graves investigation site was on the other side of the cemetery. I thought about those two sides of Oaklawn, the many sides of Tulsa, and then exited Oaklawn the way all vehicles must, by heading down 11th Street, the old Route 66—the Mother Road—through a city that felt more haunted than ever.

Footnotes

- “Committee of 100,” Tulsa Tribune, February 11, 1917. Return to content at reference 1↩

- “Tells Truths About Teeming Tulsa In “The Tulsa Spirit,” Tulsa Tribune, May 26, 1918Return to content at reference 2↩

- “Many Seek Work Here,” Tulsa Tribune, May 27, 1920 Return to content at reference 3↩

- “Bank Plans Building Homes For Employes,” Tulsa Tribune, Dec. 4, 1917 Return to content at reference 4↩

- “Three Cities Face Large Housing Shortage,” Harlow’s Weekly, October 2, 1918Return to content at reference 5↩

- The nickname for members of the I.W.W.Return to content at reference 6↩

- This was from the notorious “Get Out the Hemp” editorial of November 9, 1917 in the Tulsa World. Return to content at reference 7↩

- The event was actually carried out by the Knights of Liberty, who wore black robes styled like the Klan’s. The confusion between the Klan and the Knights is understandable, since the victims of the attack later identified members of the Knights who joined the Klan as well. See the front page of the Tulsa World, November 10, 2025. Return to content at reference 8↩

- The killing of Joe Sring (also spelled Sing) was widely reported in Tulsa newspapers, as was the exoneration of his killer. The most thorough report was done by the Tulsa Democrat on March 24, 1918, in an article titled “Waiter Shot for Making War Remark.”Return to content at reference 9↩

- See “The End of the American Dream? The Dark History of America First.”Return to content at reference 10↩

- The editorial page of the Tulsa World on August 1, 1919 called for the “everlasting” censorship of I.W.W. materials and hopes for the death of Big Bill Haywood along with a denunciation of “social equality” for African-Americans. Preaching social equality of Blacks, Lorton wrote, “can result in nothing but harm.” See “Haywood’s Defiance” and “The Race Problem,” published on August 1, 1919.Return to content at reference 11↩

- The Council of Defense installed a whistle at the power plant that could be heard around the city. If the whistle went off, the Home Guard and the Council of Defence would take up arms and prepare for warfare against foreign invaders. The whistle would go off on the morning of June 1, 1921 and unleash a wave of violence that was unprecedented in the city’s history.Return to content at reference 12↩

- “Miller Exonerated in Sring’s Killing,” Tulsa World, March 27, 1918. Return to content at reference 13↩

- Ibid. Return to content at reference 14↩

- “Killer of Ivanoff Freed of Charges Amid Great Cheers,” Tulsa Tribune, April 3, 1918. Return to content at reference 15↩

- In the long run, these cases were excised from Tulsa’s collective memory, but they established a pattern familiar to victims of police violence a century later. The cases may recall modern acts of violence involving police in Tulsa. Return to content at reference 16↩

- Eugene Lyons’ account of his time in Tulsa, along with a riveting story of Krieger’s trial is found in a chapter called “A Clowning Called Justice” in his book Assignment in Utopia, published in 1937. Lyons wrote that the experience in Tulsa was “rich and tight-packed with impressions.” Assignment in Utopia achieved notoriety in the 1930s for its portrayal of Stalin’s brutal repression of Soviet citizens, but the chapter on the Krieger trial in Tulsa is a deep cut that is every bit as violent, wild, and funny as the first season of the TV show Tulsa King. Return to content at reference 17↩

- Assignment in Utopia, p. 16.Return to content at reference 18↩

- Assignment in Utopia, p. 15Return to content at reference 19↩

- One of the criminals was a man named Hubert Vowells, who claimed he had agreed to a $125 payment to carry out Krieger’s plan. Vowells’ supposed accomplices, Frank Benson and John Hall, stole the dynamite a few days before the bombing and placed it under Pew’s home late at night. Hall said he went to collect money from Krieger, who failed to come through: Krieger was not only a traitorous Wobbly, but a scammer as well. Return to content at reference 20↩

- “Krieger’s Fate to Jury Today,” Tulsa World, November 8, 1919. Return to content at reference 21↩

- In 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Standard Oil was operating as a monopoly and ordered it broken up. Standard split into “baby Standards,” many of which, in time, became behemoths in their own right (Exxon and Chevron are two of the children). Rockefeller actually increased his wealth after the breakup because he retained a controlling interest in the stocks of these companies. Observing Rockefeller’s control over the oil patch, the writer Upton Sinclair wrote in The Brass Check: A Study of American Journalism, “In Oklahoma, nearly everything is Standard Oil.” Return to content at reference 22↩

- Fun fact: one of the Standard-allied people in Tulsa at the time was my great-grandfather, Russell Cobb I, whose first job out of Harvard was with a Standard Oil outfit called Carter Oil Company in 1919. Return to content at reference 23↩

- Cole confided in Eugene Lyons that he was unimpressed with Moss’s conspiracy theory. In court, Cole sat smoking a cigar under a “No Smoking” sign, noting, as Lyons had, the gunmen and vigilantes who came and went as they pleased. Lyons developed a friendship with the judge and the two often shared doughnuts. The court stenographer would call Lyons to warn him and his colleagues if someone threatening appeared in court. Return to content at reference 24↩

- Oil, Wheat and Wobblies, University of Oklahoma Press, 1988, p. 131. Return to content at reference 25↩

- “Charles Page in the Fraudulent Role of Injured Innocence,” Tulsa World, June 12, 1917. Return to content at reference 26↩

- Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia, pp. 15-18. Return to content at reference 27↩

- Assignment in Utopia, p. 19. Return to content at reference 28↩

- Hubert Vowells caved. He admitted he only met Krieger in jail after the bombing of Pew’s house. Now Vowells and Hall confirmed Krieger’s statements with only Benson continuing to insist on a conspiracy led by Krieger. Return to content at reference 29↩