When your rooster crows at the break of dawn

Look out your window and I'll be gone

You're the reason I'm a-traveling on

But don't think twice, it's all right

-Bob Dylan, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright”

Sean Stanford pulls on a vape from behind an Oak Tree Books countertop piled so high with books that he can’t see the door. He sports a salt-and-pepper David Cross beard and wears thick glasses, his eyes underneath sometimes darting around the store as if a book might, out of nowhere, slip off the shelves. As he scans from shelf to shelf, Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice (It’s Alright)” wheezes from the speakers, as vintage, quiet, contemplative, and analog as the bookstore itself.

From 1993 to 2017, Oak Tree served as Tulsa’s rare books paradise. While not totally averse to the run-of-the-mill bestseller, its book selection was more like a collection in a museum, with first editions and signed copies and old books kept in immaculate conditions. During those years, it was, above all things, a place to find an exquisite book.

Its closure in 2017 meant more than just the loss of a bookstore, says Jeff Martin, co-founder of Magic City Books and president of the Tulsa Literary Coalition. It meant the loss of discovery in Tulsa’s reading culture. “That was one of the great things about it,” he says. “You were going to find things that were out of print or things you just would never run across. … It felt like part of the ecosystem was gone.”

That ecosystem was unlike anything else in Tulsa, Martin says. The people running the store—Scott Dingman, Lee Roy Chapman, and Sean Stanford, among others—paved an unlikely path as a small, upstart operation selling antique books at incredible prices.

But Oak Tree Books didn’t just sell stories. It lived a story of its own: one of obsession and loss, presence and absence, taste and tragedy. It helped Lee Roy Chapman, one of Tulsa’s most lauded independent historians and archivists, establish footholds for his work at the Center for Public Secrets before his untimely death in 2015.

By the time the shop closed two years later, Sean Stanford had been absent for a while. But for a time, he was an integral part of Oak Tree: puttering around inside it, calling its phones, talking to its employees, avoiding its employees, becoming an employee, shutting it down, running away from it, thinking about it.

Oak Tree reopened late last year, forging a new path in a bookbuying environment somehow even more dominated by massive forces like Amazon and social media than it was in 2017. If Oak Tree can survive this time, it will be due to the passion of a few people obsessed with good taste. And in a world full of AI bullshit and algorithmic reading recommendations, with the constant threat of our reading lives being taken over by the dumbest ones and zeros imaginable, having a bastion of good taste in Tulsa might be more important than ever.

In Oak Tree’s reincarnation, after more than a decade away, Sean Stanford is back as the sole employee. Many argue that he’s the only one who could pull it off. He’s probably the only person who would want to.

***

Businessman Scott Dingman founded Oak Tree Books at 2812 E. 15th Street (the same location it’s at now) with soccer buddy Charles Curtsinger in 1993. Dingman created the store from a mailing list, in which he sent out letters to his clientele to let them know about his latest book acquisitions. Curtsinger soon left the business, but Dingman remained, and would for twenty years.

Scott Dingman’s myth goes that he biked here all the way from Fulton, New York (just outside Syracuse) in a failed attempt to get to California, and got stuck. He brought with him the brusque straightforwardness that Oklahomans can find so jarring in northeasterners. Even more than that, according to Stanford, if Dingman sensed that someone didn’t know as much as he did—which, to be fair, was a substantial amount—he would talk down to them.

With a beard down to his chest and the face of one of Tolkien’s dwarves, Dingman was an irascible and passionate man, by Stanford’s account. “He could be the sweetest guy in the world, and he could also be a raging prick,” Stanford says. “He could be much more direct than me, and straightforward, and he seemed not to care about peoples’ feelings sometimes.… He could be pretty hurtful sometimes, but by the same token, he could also be really generous.”

Stanford would know. At 19 years old, he stopped by Oak Tree Books in 1997 on a tip from a girl he fancied who worked there. His relationship with the girl didn’t work out, but his relationship with Scott Dingman would help to shape the course of his life.

He took Dingman as a kind of father figure. The child of an early divorce, Stanford was shuttled back and forth as a kid from east to west Tulsa until his dad drifted out of the picture, and the man his mom eventually remarried proved to be abusive, he tells me. Scott Dingman was quite nice by comparison, even with all the talking down.

“[Dingman] was quite a character,” says Jeff Martin. “He was what you’d call an old school Boomer Hippie. He lined the store with memorabilia from the ‘60s and the hippie era.” Martin lived off Delaware Place, just around the corner from the store; it was his neighborhood bookshop. “Scott was in there all the time, and it was the kind of place where you could just walk in and say, ‘Hey, what should I read?’ It was basically curation on demand.”

Sean Stanford was also around a lot. “I pestered Scott,” Stanford tells me. “I’d say, ‘Hey, do you need help? Can I shelve those books?’” Eventually, Dingman started asking Stanford to watch the register while he ran errands. He paid him fifty dollars a week. Eventually that went up to fifty dollars a day, with Dingman talking about giving him a percentage of the business.

Stanford moved to Portland for a time, and when he came back, Lee Roy Chapman was working at the bookstore. Wooly, enthusiastic, and amiable, Chapman would eventually become known as the “history recovery specialist” who founded the Center for Public Secrets and, in This Land, broke the story that Tate Brady, then the namesake of the Brady District, was involved in the Tulsa Race Massacre. But at the time they met, around 2005, he was just a guy who Stanford could call up about rare books: Did he know if this was a good deal on a second printing of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test? That sort of stuff.

He calls Chapman “a wild dude,” and smiles as he remembers him. He had his prickly moments, Stanford says, but his care and consideration came first: “He became sort of a big brother to me.” It was the beginning of a friendship that would last the rest of Chapman’s life.

Know Tulsa Better

Sign up for our free newsletter, The Talegate

***

Around the time that Sean Stanford came back from Portland, Dingman wanted to expand Oak Tree Books to Sapulpa. Stanford was constantly around, and eager for work, so Dingman tapped him to run the new store. It was called Oak Tree West, and it was brutally lame. It was all back stock, Stanford says, and it was bigger, but with fewer books. And the clientele simply wasn’t the same.

“I tried to set up some events, but they weren’t great for that location. Like, I had Hannibal B. Johnson, who wrote the book on Black Wall Street, come to do a book signing. Literally no one came. I was so embarrassed and upset about it,” he remembers. Sapulpa wanted bestsellers and romance; they weren’t looking for what Stanford wanted to sell.

The store lasted for about a year before Stanford got itchy. He was in his mid-20s, and the responsibility of running a franchise bookstore in a small Tulsa suburb did not appeal to him. Plus, he and Dingman were at odds. “I was just tired of getting talked down to,” he says. “I wouldn’t call it abusive, but it felt like something like that sometimes.”

Finally, Stanford wrote a note, locked the doors, and left Oak Tree West. Dingman called. Stanford didn’t answer. It was 2007; he didn’t even have a cell phone.

He got busy doing other things. After a short stint laying carpet, Stanford sold books out of an acquaintance’s garage, and after that, he got a job in maintenance at the Tulsa City-County Library. At first he fixed toilets, then worked his way up to driving one of the library trucks, and finally worked as the assistant facilities manager for the entire library system. That’s where he met Sherri, a Kansan who had taken a research position with the library. The two married in 2010.

For a while, Stanford and Oak Tree Books ran on parallel tracks. He visited occasionally, and still called Dingman a friend, but, as he says, he needed to set some boundaries. After getting married and working at the library, most of his time was spent birding or bicycling.

In 2013, Sherri was diagnosed with stage four cancer. In July of 2015, she passed away. The very next month, Stanford’s mother died as well, of lung cancer. Stanford’s drinking got bad enough that he checked himself into rehab.

“Lee Roy [Chapman] would call me all the time,” he says. Chapman’s father had also died of cancer, Stanford says, and he understood the weight of that loss. “He’d say, ‘Hey man, let’s go out to lunch, let’s go to a movie.’ And I didn’t want to do anything. I just wanted to sit there and finish off a bottle.” In the swirling nadir of depression, addiction, and withdrawal, Stanford couldn’t bring himself to return Chapman’s calls.

Eventually, Stanford found his way out of rehab. Eager to reconnect with people, he rang up Scott Dingman who, by then in his late 60s, had retired to Sarasota, Florida.

When he answered the phone, Dingman was crying.

“He said, ‘I just can’t believe it.’ And I was like, ‘Believe what?’ He said, ‘Lee Roy’s dead.’”

Two months after the death of Sean Stanford’s wife, and one month after the death of his mother, his friend and brother figure, Lee Roy Chapman, died in September of 2015, at 46. In addition to the obvious personal and emotional tragedies, there were concrete problems to be solved. Chapman had been the sole employee running Oak Tree Books in Dingman’s absence; now there was no one to do so.

Businessman Daniel Woodul, a longtime patron of the store, purchased the inventory and took over the rent. Whitney Chapman, Lee Roy’s sister—and now the director of the Center for Public Secrets, which Lee Roy founded—and Woodul agreed to keep the store going as a tribute to Chapman.

Still, there was no one who had the knowledge to run the place. So they reached out to Sean Stanford.

He gave it a shot. In between shifts at the library, he would go to the store and attempt to get it into some kind of shape, but he didn’t have the energy. By that point, it had still only been a few months since his wife and his mother, not to mention Lee Roy, had died.

“I kind of ghosted everyone,” he says. “Whitney [Chapman] called me, and I told her I couldn’t do it. She told me she totally understood—said I needed to take care of myself. She was great. I wish I wouldn’t have ghosted everyone. I wish I would have just talked to them.”

The store needed more work than anyone was able to give. In 2017, Woodul quietly took the inventory and moved it into a warehouse downtown, then sold most of it off in bulk. In 2020, Scott Dingman passed away in Sarasota.

Meanwhile Sean Stanford, in a fit of grief, sold most of his belongings, hopped on a Greyhound to Phoenix, and bought a minivan to live out of. He tore the backseats out and built a bed into the back of it, then spent the next few years driving up and down the California coast. He reread Kerouac, worked at a dispensary: stuff that you do when three of the closest people in your life die within three months of each other.

“I just lived [in Southern California] for a while in my van,” he says. “Then I realized I was tired of it, and came back to Tulsa.” He got a job at Gardner’s, where he heard that Daniel Woodul was interested in bringing back Oak Tree Books.

“It seemed like one of those things that should naturally be done,” Woodul tells me over the phone. “Seeing that store sit empty with the old sign above it didn’t feel right.” Besides that, he says, Tulsa was sorely lacking a fine book store. “Tulsa has bookstores, but Oak Tree is a different type of store. You can walk in there and buy a book for $15,000.”

***

Sean Stanford was the first person Woodul called about running the store.

“He was the guy,” Woodul says. “He knew that store inside and out, and he knew how to do what it was known for, which was research. And he’s just a super intelligent guy. I reached out, hoping that he’d be interested. And of course he was.”

The two of them spent months building a collection worthy of the store’s name and reputation.

“Book sales out of town, garage sales, estate sales, online, anywhere you can get books, really,” Stanford tells me about where he sourced the collection. “We were looking for primarily Oklahoma and Native American books, but also offbeat literature and philosophy.” He pauses, smiles. “Good books.”

Stanford won’t tell me where he got his copy of Furrow’s End: An Anthology of Great Farm Stories (1946) once owned by Jim Thompson, the Anadarko-born writer of pulp crime like The Killer Inside Me. It’s signed by Thompson himself and goes for $10,000.

“As Lee Roy would have said, I got it at the gettin’ place.”

Seems to me that Oak Tree Books is now the gettin’ place. What I like about the shop is that you don’t have to go very far to find an exceptional book; the quantity-to-quality ratio is higher than the norm. The interior sections are full of gems like The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy and Ordeal by Hunger: The Story of the Donner Party. History buffs, literature snobs, and regional obsessives could stay lost in here for hours.

And consider the rare books you can find. Here’s a 1969 book-club copy of Slaughterhouse Five (watch out before I snatch that one). Here’s the first Esperanto edition of The Communist Manifesto for $15,000. Here’s a first edition of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for $12,000. Good books.

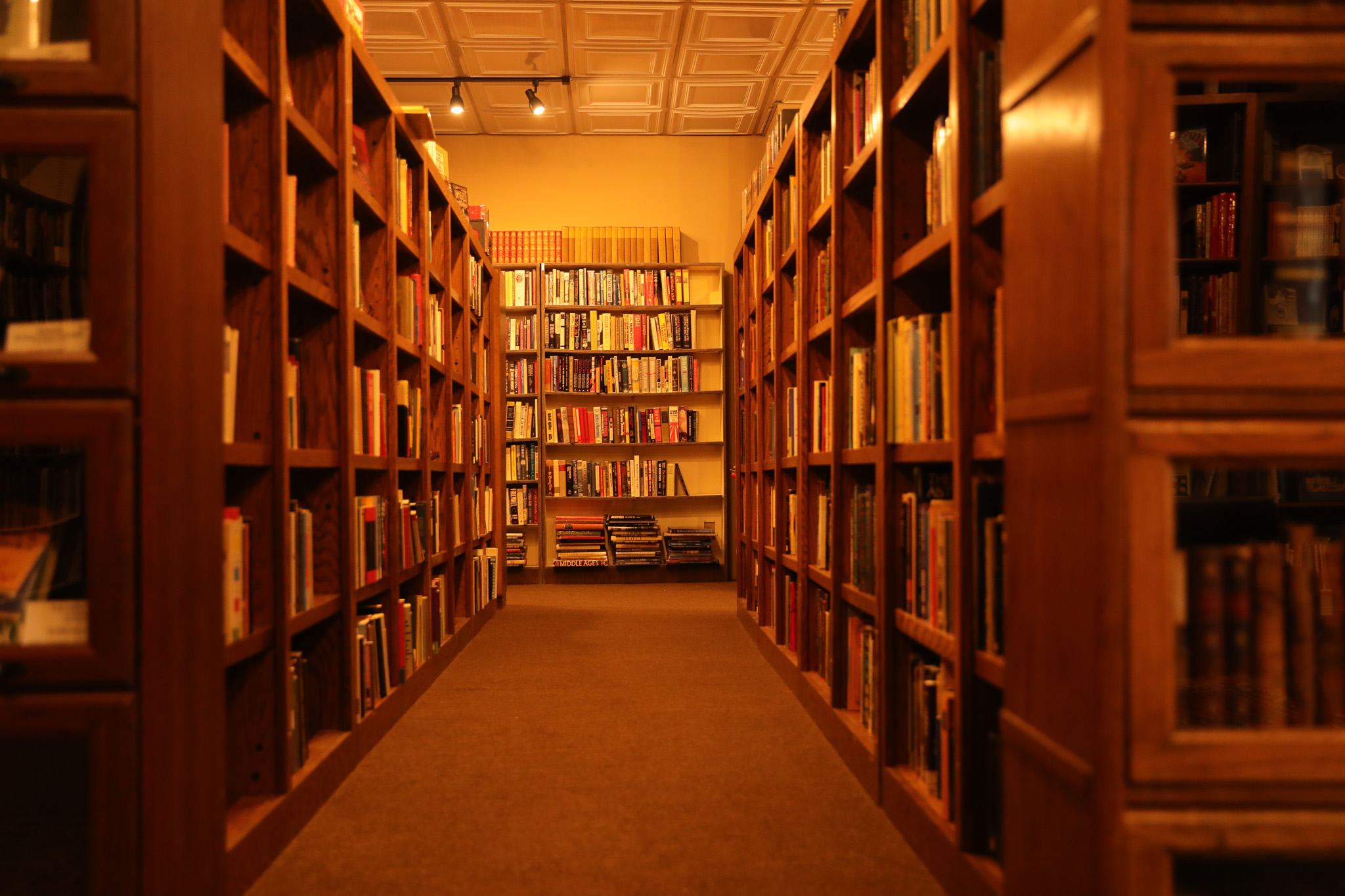

Oak Tree shows its age, too, and that honesty is rare and refreshing. This is not a hip bookstore. Its gently used wooden bookshelves and heavy leather chairs feel like remnants from a bygone era of store-keeping. It feels like a bookshop from 1950s Manhattan.

Classy framed landscapes dot the walls over the shelves. Curated selections like Homer’s Odyssey and Goethe’s Faust stand alone, daring browsers to pick them up. Not immune to such charms, I pick up and buy Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist by Walter Kaufmann and Pale Fire by Nabokov. Would I have found, let alone spent money on, these books at any other place in town?

You’ll hear Lee Roy Chapman’s name mentioned often if you hang around the store, too. It seems that the idea of Oak Tree being “a tribute to him” has materialized. It just took a little time.

In the dim, warm light, with Bob Dylan playing in the background, the shop feels like the return of an old culture of reading and thinking that’s sorely underrepresented in Tulsa: a slow, old, methodical, highly discerning kind of culture. It’s a place for rare books, rare ideas, and rare people like Sean Stanford, someone whose life has run a narrative comparable to a good book.

“Sean was part of the original lineage,” Jeff Martin tells me. “He’s the one who has all that institutional knowledge to bring back the vibe of the place.”

Martin says something that sticks with me: “I always think of bookstores in a city like patches in a quilt. They all serve a slightly different purpose. When the whole thing is working at its best, each one has its own distinct audience. If the entire city is one big bookstore, each bookstore is a different section of that bookstore.”

I ask him what he thinks the name of Oak Tree Books’ section in that metaphorical bookstore would be.

“I think it would be called, ‘Have You Heard About This One?’”