Not all grief is cut from the same cloth. Some days, it’s a weighted blanket; others it’s a tulle canopy, creating a gauzy haze between me and the rest of the world. Some days it’s not cloth at all but a cloud of fine dust that stings my nose and throat and coaxes tears from my face.

That last one is, unfortunately, not a metaphor. This is a story about how I triggered respiratory distress in an attempt to honor my heritage.

I was born in Korea but have spent most of my life in the U.S., where it’s far more normal to have a chemically treated lawn than it is to convert every patch of available dirt into something beautiful or edible, as in Korea. My Korean mom gardened a lot when I was a kid for reasons I didn’t think much about, other than that she was raised on a farm, and I thought, okay, she farmed in Korea; she farms here. I realize now that America is a country where a lot of the ingredients my mom grew up eating aren’t available unless you grow them yourself. This is less true now than it was in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, but still, to an extent, pretty true.

I didn’t have any interest in the process until I started working from home in 2020. I was home all day, and plants were some of the only living beings we knew were safe to hang out with, and I desperately needed a reason to go outside every day. I had a few potato plants, a couple of cherry tomato plants in buckets, maybe a jalapeno. It was the smallest amount of food production I could reasonably call a garden, but it worked: keeping those potatoes alive got me out of bed.

In September of that year, we lost my dad to cancer. After a long period of ordinary sadness, consideration of a future without him brought my own filial life into sharp relief. Dad was from Kentucky, and Mom is from Korea. Since Dad died, my Oklahoma family hasn’t eaten American food on any major holiday—or most any other days we’re together. None of us like turkey, and in his absence, we all felt like it was finally okay to say that out loud.

Since 2022 (when Korea started letting Americans back in) I’ve spent more time with family there than I did from ages six to 39. It’s easier, now, for Mom to leave home for weeks at a time, without Dad to care for. She needs to see her mom too, and she doesn’t like to travel alone, and I’m the child with the most flexibility and willingness to sit in economy for 14 hours. Getting to know that half of my family for the first time ever has been sobering and upsetting and exciting and lovely; only a few of them speak English, and I don’t speak Korean. The experience has created a substantial Korean emptiness in me that I need to backfill. I am grieving Dad, still. I am also grieving an imaginary, lost version of my life where I am not American.

While in Korea, I made a point to eat an entire microwave meal inside a convenience store like I’ve seen in Korean dramas. I started shopping for seeds online; it’s hard to find fresh, green Korean gochu (chile peppers) in the U.S., and they’re a common side dish for all kinds of Korean meals. I took a few daytrips from Seoul through the Korean countryside, seeing fields of baechu (Napa cabbage) and tiny yards with no grass, but instead, rows of daepa (big green onion).

It’s common in rural Korea for restaurants and homes to have adjacent gardens to grow ingredients. We visited our family’s farm, now run by one of my mom’s brothers, which specializes in a particular type of oi, or Korean cucumber.

When we left Korea in the spring of 2022, my mom’s aunt and uncle gave her a parting gift: a bag of gochugaru (literally, pepper powder), grown, dried and ground at their home. Seeing those rows of oi and tasting that gochugaru made me think, Yes, this is literally in my DNA; I can do this. I flew home from the rich, volcanic soil and temperate summers of Korea with a bunch of dumbass new ideas about what kind of Korean person I am supposed to be.

One thing about being a Korean-American my exact age is that my view of “real” Korean food is frozen in time at the point of Mom’s emigration, and she was born shortly after the Korean War. This era of Korean food is highly traditional but sadly peaked before food blogs, and so the idea that I would need my mom to write down recipes for me makes her laugh. Unfortunately, it does not make her write anything down. Most other K-moms her age aren’t writing down—or measuring—ingredients either.

Fortunately, Korean YouTuber and cookbook author Maangchi and my mom are the same age, and from the same region of Korea, so while I reside squarely in the generation of first-gen Korean-American children whose mothers refuse to help their kids make kimchi, my surrogate internet mother Maangchi would—or so I hoped— help me do things the real way.

One ingredient I go through a lot of—used in so many Korean recipes that its fiery red color is ubiquitous with a modern picture of Korean food—is gochugaru, the kind my mom’s aunt and uncle gave her. I vaguely remember Mom’s trays of drying peppers from childhood, and she still occasionally makes her own now. Seeing her great aunt and uncle grow their own fully cemented my feeling that we, all of us, are good at this.

So, for three summers straight now, I’ve grown a handful of Korean chile varieties, to which Mom says, confounded, “Why? I grow one kind.” She doesn’t understand; she doesn’t need to become Korean the way I do.

After waiting for the peppers to turn red, which takes weeks after they’ve reached full size, I dried them in the sun, lost several to the Oklahoma wind, and finished them in a dehydrator, then stored them until it looked like enough. Those three summers yielded me about four gallons of dried red peppers. I went to work.

I didn’t have a recipe—even Maangchi just explains how to choose the best gochugaru from the grocery store. And I don’t know how my ancestors did this shit, but it probably was not with an electric coffee grinder (which I had to label so that I never grind coffee with it again). I stemmed and seeded every pepper by hand, because this makes the powder redder and less spicy. If you don’t do this, I learned with a tiny test batch, it is quite literally too spicy to eat.

A few at a time, I wedged them into the grinder and pulsed for about half a minute until they looked … powdery enough. When I lifted the lid, a tiny red dust cloud poofed out directly into my face, effecting a respiratory reaction akin to inhaling a handful of cayenne. I learned this lesson an embarrassing number of times before opening the grinder in a different direction. Even with that adjustment, twenty or thirty batches in, the tiny clouds became a giant cloud, with me crying from pain and capsaicin in the middle of it. I had to keep airing out the kitchen by dramatically waving the back door open and closed, which did not work very well. Next time I will attempt this in a kitchen with two back doors.

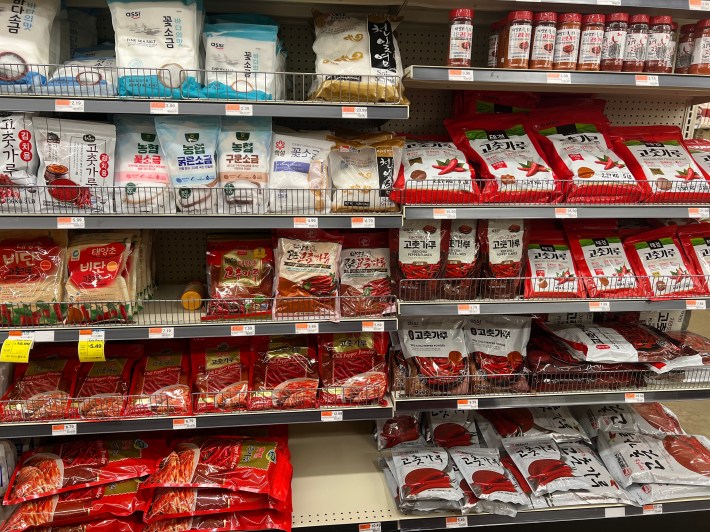

Over the course of two days, one handful at a time, I turned three years’ worth of homegrown peppers—four gallons of them—into three cups of medium-coarse gochugaru. The same amount at Pan-Asia Supermarket would have cost me about $5.

My lungs will likely never recover. And given that the powder is so scarce, and took so much effort to make, I’m too afraid to use it in case I waste it.

The imaginary Korean Me I’m getting in touch with would certainly not have grown her own gochugaru. I have Korean cousins my age in Korea, and they don’t do that. This is an invented desire, a romanticized version of getting in touch with my roots.

I’m not mirroring the behaviors of my Korean family members who are my age or close to it; they get their pepper from the store like real Koreans do. But, away from the high rises, about 90 minutes south of Seoul, part of my family grows some of their own food, because that is what you do in the country. What we do. In any country.

A thing nobody told me before my dad died is that you don’t only grieve a person directly—instead, you notice every huge or minute way that the absence of their mortal coil changes everything else about your life. Sometimes these changes don’t even present themselves until much later, and sometimes these changes work backwards, trying to change your pre-grief life.

Last year, I grew my own Napa cabbage to make my own kimchi. (It sucked.) This year, I have three varieties of Korean melon ready to put into the ground. My American self is not even a big melon guy, but I guess my Korean self is.

When my mom and I came back from Korea through Atlanta, the Customs agent opened our suitcases. He held up the gifted bag of gochugaru quizzically, looked at my mom and said, “That’s a lot of powder.”

He has no idea.