There's a whole world in Skip Hill's art. Born in south Texas, he's called places from Amsterdam to Thailand to Oklahoma City home. ("I just spent a week in Miami. That's my vibe," he says.) Conversations with Tulsans—including Quraysh Ali Lansana, with whom he collaborated on the children's book Opal's Greenwood Oasis—convinced him to try us out full time.

Two years ago, seeing the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre on the horizon, he decided to make the move. From the perspective of someone new to the city but familiar with Oklahoma (he's an OU graduate and has worked with the Tulsa arts community for years), Hill talked with us about being in Tulsa in this historic moment and took us through the layers of meaning and media in one of his large mixed-media pieces currently on view at 108 Contemporary.

With influences as wide-ranging as Gustav Klimt and his grandfather, a professional sign-painter in Alabama, Hill's work repays a close reading. Days after we talked, I'm still finding new ways to see it. He'll have more to say about his art and his process in a virtual artist talk tonight, April 22, 2021 at 7:00 pm. Stop by 108 Contemporary to take in all the detail in "My Soul Looks Back and Wonder How I Got Over," his show with Letitia Huckaby, until June 20.

ALICIA CHESSER: What's your experience of Tulsa so far?

SKIP HILL: It's growing on me. It's not exactly where I thought I'd be at this point; I was sure I'd be living back in Europe. But I love my life. And it'd be tough for me to do what I'm doing someplace like L.A. There's so many artists, so many galleries there—whereas here I can at least make an impact. I do tell young people, as soon as you get out of school, please go experience something else that you can bring back. Come up with a business idea, work for one of the big museums or whatever, and bring that energy back here.

My girlfriend's from Tulsa, and she's white. We can be in Miami and Venice and L.A. and no one gives us a second look except to say, hey, you're cute! When we come back here, there's always some dude glaring across the bar at us and I just want to say come on, man. I'm pretty comfortable navigating white spaces. I was class president of a predominantly white high school. So I have no problem being the only Black, but my African-American spidey senses tingle when I'm in an environment where I can tell there's some people who are not comfortable with me being there. It's frustrating.

But we have things we really like here. I have my places now. I like driving down Riverside; in OKC they didn't really have a river, they had a ditch. Visually Tulsa is a beautiful city, especially midtown. And I'm grateful there are people who are interested in the arts.

AC: When did you first learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre?

SH: My father was always sending me books. He had a study full of Black history and politics so early on he exposed me to things that we certainly werent given in school. I was probably a young adult when I first read about the massacre. It was hard to find much information at that time. And when I learned that it was something that Blacks and whites didn't really want to talk about, I kind felt like, well, maybe you need to leave that alone. It took moving here to really get a full sense of it. When people outside of Oklahoma think about Tulsa—if you're talking to Black people—the first thing they think of is not Cain's Ballroom. Or the Driller. Or Leon Russell or The Outsiders. If you live in Atlanta, Gainesville, Philly, Richmond, when you hear Tulsa, you think, Oh, that's where they burned down Black Wall Street. If people with power here knew the impressions of Tulsa—not as they wish it to be, but how other people see it, how it's more tied to the race massacre than anything else—then maybe they would want to face it.

More people are learning about it; for a lot of people that happened through Watchmen. But there's this compulsion here to keep things the way they are. If you grew up in Tulsa in the 1950s, you want it to be like it was in your glory days. That being said, I do encounter people of that age group who approach me about my show. You know, this small white lady coming up to me saying, "I just love what you're doing. We need this. This is what I want to see."

AC: How does that change get to be more sustainable here?

SH: If Tulsa would embrace this history, we'd be a much more vibrant-looking and attractive place to people. It's tough work, but so is maintaining the illusion that everything's right. An alcoholic cant even begin to work on sobriety until they acknowledge that they're an alcoholic. You have to acknowledge what you are. And once you take the band-aid off, then you can start healing. What I'm saying is all the things that you're denying are the things that could make this place awesome. If you address it. If you acknowledge it. If you put your money into it, put your policy into it. If you were doing that, people in other places would start saying, "Tulsa is the mark that we want to reach. How they've taken a community trauma and turned that thing around is admirable." And you'd have people from all over the world coming here to find out how to do that.

I'm talking pie in the sky. But the fact of the matter is, it's within reach for Tulsa to take your trauma and turn it around to your glory, turn it into a positive story. I was just talking to a guy from South Africa who was telling me how amazing it is there now because they've done that work. In most cases it's a one by one thing. You can't mandate evolution. You have to know somebody before you can start challenging what you don't know. Once you know someone, then you can see them as a person, as opposed to being part of a category of people. That's why the power structure of white supremacy has always worked so hard to keep people apart.

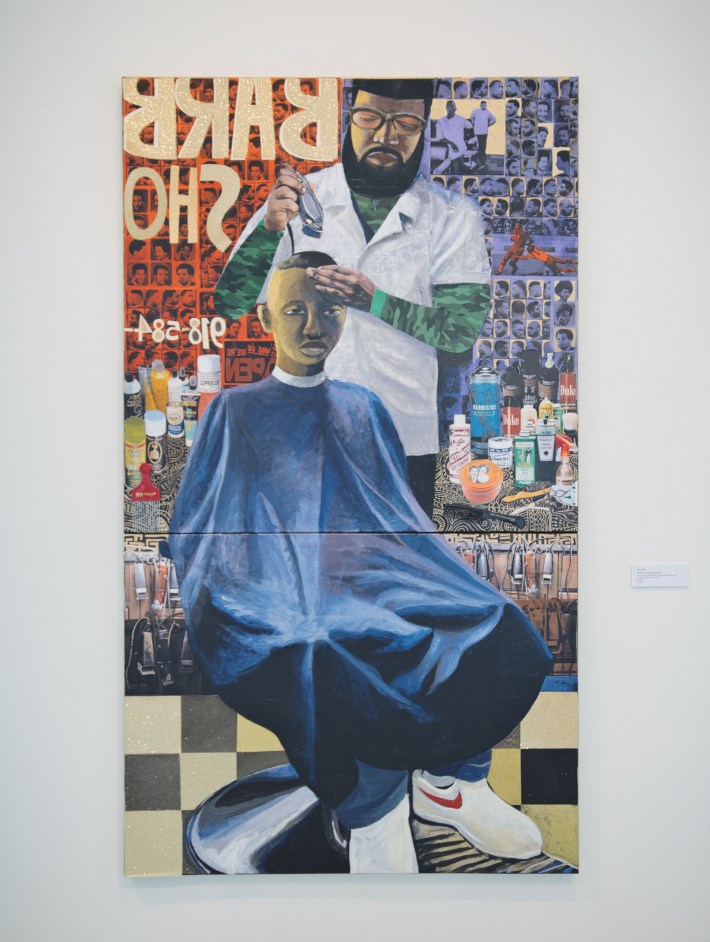

AC: Encountering people one by one, getting to know somebody in a very up close and personal way—that is totally what's happening in these big pieces. What I feel standing in front of them is the total assurance of who these people are within themselves.

SH: That's exactly what I hope for. I liked the idea of the viewer stepping in, having a seat across from the beautician, with the client in the chair. I want the viewer to have a sense of being in the room. Sometimes that viewer is a Black person for whom this is a familiar environment. Sometimes it's a white woman of a certain age and income level who most likely would never have been in a Black barbershop. Let us invite you into one and give you a sense of just the basic human dignity of the people in the space. Here in Barber Shop (Edge Up), there are collage elements from Black hairstyle posters, which every Black barbershop has (even though I've never heard anyone say, "Hey man, I want number 13," they're ubiquitous), and which in a subconscious way are an affirmation of Black male identity. I thought about the economics of Black hair care, how much money African-Americans spend on products and who owns those companies. (Donnie's, a '70s brand you see here, was a Tulsa haircare conglomerate. Schwarzkopf, a modern brand, translates to "black head," which is the kind of little detail I love.) There's the pick and the comb, harking back to high school when white classmates would always want to touch my afro. Those guys are now 60 years old; they're gonna recognize that pick! And of course you have some Nike sneakers. Their first major phase came from a Black man playing basketball; yeah, Michael Jordan got rich off of Nike but not nearly as rich as Nike got from him.

Having some things that Black viewers could immediately identify with was important—and in doing so they recognize, "This is a part of my world that's being elevated and placed in a forum where I don't see myself every day." The reason why this barber and beautician are the predominant figures in these works, as opposed to a doctor or a lawyer, is that in a culture where everything about you has been labeled ugly—the color of your skin, your nose, your lips, the texture of your hair—a barbershop was a place where you could feel your dignity and your sense of beauty within yourself. This is all about you. You're the center of focus. You want to be looking better, feeling better, ready to take on the world—when the world has told you there's nothing you can do to make yourself acceptable.

Plus, you just spent the last 40 minutes in the company of other people like you. In earlier times, black people couldn't necessarily gather and laugh out loud together on the street, right? It's the one place where there's a sense of community safety. And there's the intimacy of the relationship between the barber and the client. When I was growing up, my mom was in between marriages. There were times when the only men I encountered were in that barbershop. So I've got this man—my hometown barber's name was Mr. Ferguson—who I'm familiar with, who I trust, who's got his hand on my head. He's right there and I smell his breath and everything, the man-ness, you know! He's saying, "Pull your ear down. Tilt your head over." It was all done with great care. As a black boy, it was very protective: a sense of security. In the barber's chair, everyone's a king.