Max Comer can’t stop going viral.

He’s better known online as @airplanefactswithmax, an Instagram/TikTok account known for explanatory videos about airplane technology that unexpectedly pivot into factoid-laced summations of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. They’re funny, they’re dry, and they provoke a frenzy of online activity. Across Instagram, TikTok, and the occasional Thread, he’s gathered around 1.3 million followers in two years, and that number keeps climbing. His Instagram Reels get 200,000 views and 300 comments when they don’t do well; his high-performing videos get over 38 million (that’s 38,000,000) views and 16,000 comments when they reach cruising velocity.

I’m an airplane mechanic, Max will say, staring into the iPhone camera, and this is an airplane fact with Max. He'll be in what seems to be the hangar bay of an airport, explaining to you the purpose of, say, a 787’s window. Something that makes these 787 windows a little different, he’ll say, is how they can fade to black at the touch of a button. And yet what makes this fading a little different than the fading that Frodo experienced after he was stabbed by a Nazgul on top of Weathertop in The Lord of the Rings—and here he’ll somehow avoid cracking a smile—is that this window actually doesn’t begin to fade because of the evils contained within the Morgul blade which was carried by the Witch King of Angmar which resulted in Frodo having to be carried on horseback by Glorfindel to Rivendell before—he must be nearly out of breath—they were eventually able to lose the pursuing Nazgul when they were swept away in the flooding at the Ford of Bruinen, but—and here he’ll pause—this 787 window darkens electronically, and I think this window shade is pretty cool, so … yep.

That’s the whole shtick. Max has made just over a hundred of these, and their success has made him a massively popular figure both in the airplane maintenance world—so much so that the Federal Aviation Administration had him on their podcast—and in the Lord of the Rings fandom—so much so that the Amazon Prime show The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power flew him out to Comic-Con in 2024, just because. It’s possible that Max Comer is the biggest Lord of the Rings influencer on the internet. He’s also, as far as I can tell, the biggest influencer in Tulsa, period. Consider a massive Tulsa name like Hanson, with 500,000 followers; Max has them doubled and then some.

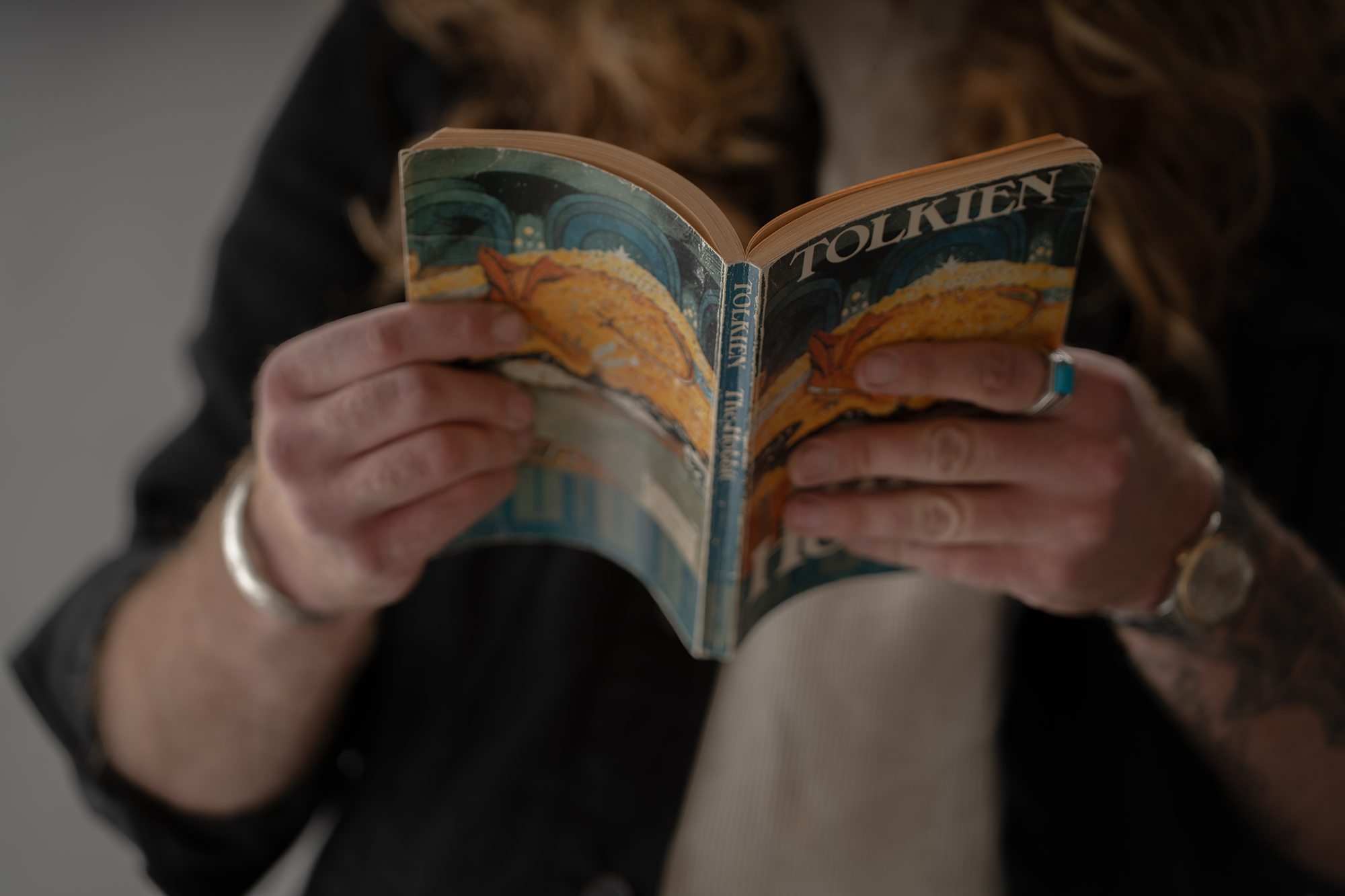

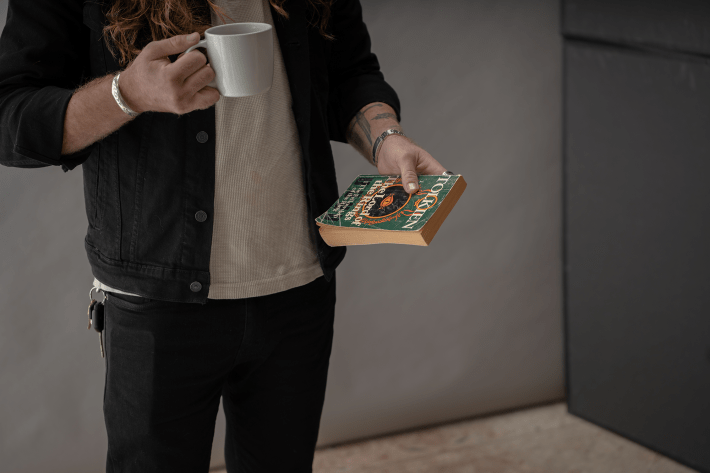

But he didn’t set out to become a viral sensation. He’s just a guy who loves Tolkien and works on airplanes for a living. In his house on the outskirts of Tulsa, where he lives with his two sons and two dogs, he shows me his battered copy of The Silmarillion, Tolkien’s collection of myths connecting the backstories of The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien, he admits, is one of the few things he reads lately. On his bookshelves are weightier titles: issues of Jacobin, The Color of Law, various histories of the United States. But that’s bookshelf stuff; not much other than fiction appeals to him lately.

Tolkien, obviously, is a repeat destination. He read Frank Herbert’s Dune last year, which he loved. Incredibly, he also read Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona, which he calls “this really horrible book,” from a recommendation. “I said, get that shit out of here. I went right back to Tolkien.”

He swears a surprising amount for someone whose claim to fame sounds like a children’s television show, but it’s only surprising until I remember that he’s an airplane mechanic. At six feet tall, he wears his curly hair past his shoulders and sports a thick mustache with a wide hill of red stubble under it. If you put a helmet on him, he’d look like an extra in the Rohirrim.

While we talk in his living room, his face is being licked by one of his dogs, Beetlejuice, whom he and his wife found chained and starving in the back of an abandoned house in their neighborhood. Beetlejuice is the only dog that Max will let inside while I’m here. The other one stays in the backyard, because, as he says, “He’s a crazy jerk; he’ll kill you.” That’s funny, to him, because they raised the aggressive one from a puppy and he turned out all crazy jerk, while the sweet one endured absolute misery and turned into a good boy with big eyes and a need for affection.

Nature and nurture, I suggest, have funny ways of turning in on each other. Max nods and stamps his finger emphatically on The Silmarrilion’s cover. He’s dealt with his own series of turns. Life has been strange for him, to say the least, for the last two years, and his favorite coping mechanism is reading Tolkien.

He admits that it’s escapism. He thinks—and Tolkien would agree—that that’s not a bad thing. Sure, he says, lots of people call Lord of the Rings an allegory, reading, say, Saruman as some metaphor for what Tolkien thought about industrialization. He thinks for a second, scratches the stubble on his cheek.

“To me, it’s a story about Aragorn.”

This is a story about a lot of things. It’s a story about love; it’s a story about loss; it’s a story about—indulge me here—unexpected journeys. This is a story about Max.

* * *

Max Comer is 33. He lived the bulk of his early life outside Denver, where he spent his childhood skiing with his older brother, hiking, and working on his grandfather’s alfalfa farm during the summers. He learned guitar and played in bands during his time at Columbine High School—the same Columbine High School where the deadliest school shooting in American history until Parkland took place. When that shooting happened, Max was still in second grade at Dutch Creek Elementary, a mile and a half away. He still recalls high school kids arriving out of breath to Dutch Creek that afternoon. “They were sitting in our hallways, just crying, and we were locked in our classrooms. It was a crazy day. We were locked down for a long time.”

He’s surprisingly sanguine about his proximity to the epicenter of one of our largest national tragedies, but then, for most of his life, the Columbine shooting simply wasn’t happening. He was a nerdy kid in a Denver suburb who started reading Tolkien at 10 and played with his pop-punk alternative high school band, Quote the Raven. Surely he means Quoth the Raven? He shakes his head and smiles. “No, dude. Quote the Raven.”

Sign up for The Talegate, our free newsletter

Get Tulsa’s best stories delivered every Tuesday and Friday

He went to college for history, but after three semesters he found the college experience less enticing than the crackle of his black Crate Electra Strat-Style guitar through an amp. He thought he might want to be a rock star. He dropped out and got a job waiting tables at an Olive Garden. They wanted him on the clock at 10:30 in the morning, which to a 19-year-old “is the crack of dawn,” so, you know: Artistic differences. (He got fired.) He bounced around, figured out how to bartend between working on songs with his band, and landed at a spot called Tom’s Urban 24, now defunct.

That’s where he met Jones—Jonessa, actually: at a Tom’s Urban 24 work meeting, 2013. Her hair was half-auburn and half-blonde, and she wore black Vans—just like Max wore. “I like your shoes.” That was his opening line. It’s not a bad one. She was six months older than him. She was also a bartender, foul-mouthed, funny: just like Max.

But where Max was shy, Jones was bubbly. Where he wanted to observe from the corner, she wandered out into the center, lighting up rooms with her distinctive laugh and blue-green eyes. She asked him out to a movie, and soon they had a baby, and one night Max stopped in the middle of a show he was playing to pop the question, surrounded by their friends. They married in 2017.

But as they soon found out, running a two-bartender-parent household required a near-untenable amount of elbow grease. Max and Jones became ships in each other's nights, passing off the baby on the way out the door to closing shifts. He started looking for alternatives.

A friend was going through Airframe and Powerplant school, where you learn how to work on airplanes. Max had always been a handy kid, tinkering with jeep engines on his grandpa’s farm. “Plus,” he says, “I needed health insurance.”

He’d go to school from seven in the morning until three in the afternoon, then bartend until two in the morning. “And then sometimes I worked part-time in a warehouse.” I pause, calculating hours in my head. He goes on: “And I also had a part-time job out at Denver International Airport doing ramping and de-icing for the aircraft.” The baby was growing. Jones was bartending full-time. Max describes this period of life this way: “It sucked.”

After graduation, they moved to Spokane, where Max fixed planes on the runway in 10-degree weather in the middle of the night, which also sucked. Jones and Max had a second kid before coming back to Denver, and Max got a good union job fixing trains. But in 2019, the price of real estate in Denver was approaching one of its many ridiculous and terrible zeniths. They couldn’t afford to buy, and with, now, two kids, they wanted to. Add the fact that their main babysitter had decided to move to—where?—Oklahoma?

At first the idea entered their lives as a cruel joke: “Maybe we’ll follow her to Oklahoma.” And then, when they looked on Zillow, the joke seemed a little less cruel. And then, when they realized that there were plenty of aircraft maintenance jobs in Tulsa, what was once a cruel joke soon became settled fact.

They moved down to Tulsa at what I think you’ll agree is the perfect time to move to a city you’ve never been to before: January of 2020. Yes, two months before the pandemic, they found an old Victorian-style house to buy, they bought it, and life somehow worked. When COVID hit, Max feared for months that he’d be laid off, but as he says, “Planes do not like sitting. They like flying.” Which is to say that planes are a lot like cars, and maybe like people: If you let them sit for too long, they’ll get all weird. Thus Max retained a measure of indispensability that kept him with a job through the layoffs, against all odds.

Then, on September 10, 2022, Jones, by then his wife of five years, died suddenly. (Max has asked me not to go into the details of this, though he’s told them to me. His children are 10 and six, and he wants them to find out from him, and not some random internet writer; this is a request I feel I must respect.) They held the memorial in Denver. When Max Comer came back to the big Victorian, with two dogs, and two sons, and a mortgage, in a state where he had no family, he was a widower.

Max gets up to turn over the record: Buckingham Nicks. It’s the album that Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks made before joining Fleetwood Mac, whose cover has the two of them shirtless in front of the camera. I don’t think he likes talking about Jones’ death—who would? He wants to talk about Buckingham Nicks. Do I know, he asks, that the album has never been re-pressed?

The word snags on something in my mind. Repression—the psychological kind, where you unconsciously push bad thoughts away—is inevitable in a sudden, traumatic experience. By that point in the year, Max had used up all of his sick days at work, and Jones had no life insurance, and the only leave his company was offering was unpaid, so he went back to work after only a week and change. Rent to be paid, kids to be raised.

Family helped. A GoFundMe plugged in a bunch of lost income. His parents and Jones’s friends flew down to help with the kids. Even so, spending your days in the guts of an airplane, surrounded by other airplane mechanics, doesn’t exactly lend itself to healing deep psychological wounds. Grief is a lonely weight to bear, and over time, Max found himself reaching out in ways unorthodox.

At the time, his Instagram account was private and personal, mainly for pictures of his family. He had 300 followers. Of course, he posted about the loss, and of course, people responded in kind with kind words. But social media’s memory is short, and soon, people moved on. Max still wanted to talk.

So one day a few months out from Jones’s death, at work waiting for his maintenance crew to show up, he whipped out his phone and started filming himself. Look, he said: this is a landing gear actuator. It’s my favorite part of the airplane. It’s pretty cool. So … yep.

He didn’t know why he was doing it, or why he spoke in near-monotone—what some might call deadpan, and which he calls “just dead inside”—or why he posted it on his Instagram Story to his 300 followers. But the response was eerily immediate: his friends found it funny. They responded in his Direct Messages, inevitably asking how he was doing, how he was dealing with the loss. This cycle of posting became a way to find light in the fog of grief: a cure for brainrot, via, bizarrely, the techniques of brainrot.

It was a fun relief. Every once in a while, when the pressure of depression threatened to crush him, he’d make a silly, deadpan video and post it to his private Instagram. And eventually, through many friends' coercion, he posted one publicly, on TikTok.

He did it on his lunch break. He'd made a video about airplane tires being different from car tires—because, you see, airplane tires are installed on airplanes. “Which is cool,” he said at the end, referring to the fact that these tires are different from those tires. Nothing deep. Just a little self-referential humor to get through the day. Which is cool. He posted it, then leaned back in his break chair and took a nap. It was barely three months since Jones had died; sleep was hard to come by.

When he woke up, his phone was flooded. By the end of the day, the video had 100,000 views. “All I was doing was saying what the airplane tire was. But it was like.…” He runs out of words and makes a motion like he’s feverishly scrolling down a phone screen, then shrugs. To him, the response was—and still in a way is—completely out of proportion.

“Dude,” his coworkers told him that day, “you showed up on my TikTok.”

He made a few more. It was that or be consumed by the dread, so why not? The follower counts were rising: 8,000; 12,000; 20,000. It was a little overwhelming. What if his employer found out? He didn’t know if showing the underbellies of airplanes was strictly allowed. He took a break from posting. The Rings of Power, that Lord of the Rings prequel series, had just come out. It was, he says, the only thing he could focus on that wasn’t pictures or videos of his late wife.

Depression is like that. Tolkien again tonight, huh? You bet. And when he was done with The Rings of Power, he reread the books, as you do, for the seventh or eighth time.

Somewhere inside all those days spent in deep Tolkien lore, a thought began to form, taking root while he turned screws and emptied hydraulic fluid. Here were two complex systems—one literary and one physical—that he rarely stopped thinking about. A mind in depression will often turn to racing thoughts as a symptom. Max’s mind flipped through Tolkien and airplanes like infinite rolodexes, sparking strange synchronicities that made more sense when he considered them in the context of his odd, matter-of-fact videos. Like, hey, couldn’t this whole thing be a little funnier if I pivoted into Lord of the Rings for some reason? An aircraft has a blade, just like Aragorn does. Andúril, yeah, that’s the one. The Flame of the West, The Sword Reforged, The Blade That Cut The Ring From Sauron’s Finger.… You get it.

He made his first combination video in early 2023. For a week, it sat at five likes, forgotten. And then the algorithm swooped in and changed Max’s life.

Instagram loved it. The reaction was immediate, positive, and ravenous. Suddenly, 20,000 people wanted this ultra-niche, hyper-specific thing. More Lord of the Rings slash airplane maintenance content, the audience screamed, and Max, a person who is perhaps more qualified than anyone on earth to offer such content, acquiesced, even as he barely understood why he was making it, or why people wanted it in the first place.

“It’s just a thing I started to do,” he says, standing on his front porch and lighting a blue American Spirit. He lost all the trees in his yard in a tornado last year; it jumped over his house while he held his boys in an interior closet. He looks out into the bare yard. “It was a way to feel less shitty.”

Soon enough the 20,000 Instagram followers turned into 100,000. That was cool, too, and impossible to imagine. And then that doubled. The more he posted, the more people tuned in to see him pepper the camera with deep Tolkien lore (which he claims to have memorized and does not write down for his videos). 500,000 turned into 800,000.

There are many reasons for this popularity. For starters, Max’s dry approach to airplane explanation tends to resonate with anxious flyers. As one commenter noted, “He inspires confidence.” Seeing a pro mechanic surrounded by disembowled airplanes dissect a fearful-or-fearmongering video about something like wing bend during turbulence can give people a grounded understanding of plane issues.

Also, people fucking love Lord of the Rings. Max’s followers sometimes call him “The Lord of the Wings,” and they live for the moment when the grist of airplane mechanics gets fed into the mill of Tolkien lore. You may be shocked to hear this, but nerds love nerdy shit, and hearing their favorite nerdy little tidbit get airtime from a funny guy on Instagram with long luscious hair is probably the closest they get to intimacy! Ba-zing! I’m joking, of course. Lord of the Rings fans do have sex; otherwise Peter Jackson wouldn’t have had an audience.

Max’s vast array of hardcore band t-shirts, which he sports in the videos, also gets him a fair amount of fans. Inevitably on a video, multiple viewers will comment on the band that he’s wearing. He’s even had the bands reach out to him, offering to hang out on their way through town. Wearing hardcore tees has become one of the bits that he commits to, and as he says of himself: “I am nothing if not committed to the bit.”

When I talk to him on his porch, he’s just hit one million followers on Instagram, a milestone no matter how you slice it. He promised his followers that when he hit one million, he would get a tattoo of The Oath of Fëanor (some deep-in-the-weeds Silmarillion stuff that’s so obscure it’ll make any civilian’s eyes glaze over), in Elvish, on his ribs. His followers loved the idea; Max regrets agreeing to get that much ink on such a sensitive area. This is what happens when you commit to the bit.

As far as I can tell, Max Comer is the most-followed Lord of the Rings influencer on the internet, which is as strange a superlative as it gets. And a more reluctant influencer there might not be. At the end of the day, he’s just a guy who really loves the stuff he loves. He’s a homebody who likes to play video games, write songs on his guitar, listen to hardcore, play World of WarCraft, and skateboard with his kids. From my conversations with him, I don’t think there’s a single follower or ounce of online clout that he wouldn’t trade to have his wife back.

Jones used to tease him about Lord of the Rings. She never understood why he was reading Tolkien again. “It would have broken her brain that I had 10,000 people following me, much less one million. If she were alive, I would have had merchandise the second it started happening. She was good at that sort of thing.” Max says people have asked for merch, but he worries about making low-quality crap just to make some money.

He’s got a job; the account is just a hobby. It was Jones’s hobby too, weirdly: she was a social media fiend, Max tells me, a true scroller who loved posting cleaning hacks on her Instagram. “It’s nice to connect with her in that way. Sometimes I’m like, maybe this was all her doing. Like she’s saying, yeah, I’m gonna push up his follower count and mess with his head. Ghost algorithm.”

There are worse ways to cope with the sudden death of a partner than to post incongruously aircraft-related deep-dives into Lord of the Rings lore online. Whatever he thinks about internet stardom, he’s happy with the work he’s put into the videos. “I’m proud of myself for persevering through [that time],” he says. “At a certain point I chose to keep making videos. I decided I like doing this. It made me look forward to going to work, and seeing people respond, and laugh, that really made me feel good at the time I really needed it. I got to put some positivity out into the world. It made me feel better.”

Confoundingly enough, it makes other people feel better too. Max gets people in his comments all the time talking about how much it makes their day to see his videos. I’ve seen a person claim that he was their inspiration to go to Airframe and Powerplant school. In the few posts in which he talks about Jones’s death, some of his followers acknowledge their own losses, post about their own grief, find comfort in suffering now shared.

Don’t blame me for getting sentimental here. There’s an ethos in Tolkien that encourages a silver-lining mentality. The characters go through hell because they have no other choice, because the route to hell is the only path to salvation. What they then find on the other side of hell is a series of beautiful, strange communities who embrace them for what they’ve gone through.

“I wish the Ring had never come to me; I wish none of this had happened,” Frodo tells Gandalf deep in the Mines of Moria. “So do all who live to see such times,” Gandalf responds. “But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.” Max decided to post through it.

* * *

Since Jones’s death, Max has been writing these dark, angry songs about disappearance and loss. They remind me a little of John Moreland, who, in fact, reacted with a clapping hands emoji on his most recent song video. Maybe, Max says, that tornado hopping over his house made him a bonafide Oklahoman. He’s got some recordings on Spotify, where he has about 1,100 monthly listeners; his EP, EP, came out last year, on his 33rd birthday. On the cover is a series of photographs his grandfather took at his family’s old ranch in Colorado, where Max grew up learning how to fix things.

Sometimes things have to be fixed. Sometimes you just have to take a bad situation and run with it. Sometimes someone gives you a burden you’re not able to shoulder, and you shoulder it anyway.

On a cold, drizzly Friday night, I head to Saint Cecilia’s to see Max play at Songwriter Night, an open mic where the venue’s crew records the songwriters’ performances. This is a big night for Max; he’s never sung live in front of anyone besides his kids or Instagram/TikTok Live before. The audience numbers 12, including him, but he’s still nervous, snapping his fingers and tapping his dark blue sneakers in the lamplight. On his shirt is an illustration from GODSTEETH, a Welsh artist, depicting a heavily-armored cleric with a mace, with the words HOBBIT HUNTER below the illustration. On brand.

He gets up there and sings three songs in a gruff, husky voice, a stark pivot from his everyday cadence, which is (despite his deadpan videos) quite jovial and varied. “I’d like to be Dallas Green [of City and Colour], really high and beautiful,” he tells me, “but my voice just doesn’t sound like that.” When he belts out these songs, I can tell he means them. “You left me with a wandering heart/Took your things and now you’re gone” sounds like a line about a breakup. In Max’s case, the implications are harsher, even as he protects the listener from that reality through the comfort of music. In this way his songs are similar to his videos, which work as a smile pasted over a deeply depressed interior: one function, at least, of art.

When he’s done, I head back out into the cold rain. I think about the long strange arc of the last two years of Max Comer’s life. Here’s this quiet, shy airplane mechanic who was thrust into very real internet fame—he gets approached by strangers on the street sometimes and asked for pictures—by virtue of a coping strategy he accidentally developed after the loss of his wife, a social-media obsessed social butterfly who had no love for flying or for The Lord of the Rings. Nature and nurture sometimes turn in on one another. Yin and yang contain each other’s attributes—like two pairs of black Vans on two very different people. I have this theory that when people die, their qualities spread like vapor into the hearts of the beloved who survive. Maybe Jones’s soul nestled in Max’s heart—maybe even in his phone, her “ghost algorithm” somehow helping him stay tethered to the world. Which would be cool.

In the meantime, life goes on for Max. It’s been just over two years. He’s still got pictures of her all over the house. The houseplants that she was able to keep alive, he’s somehow been able to keep alive, too, despite his claim that he doesn’t have her green thumb. He fixes airplanes, reads Tolkien, skateboards with his kids, and plays World of WarCraft after they go to sleep. I don’t get the sense that he’s about to quit his job and go creative; he’s too invested in raising his boys for that. But it’s good to see him up there in front of those 12 people at Songwriter Night, doing something that makes him feel a little anxious and twitchy and alive.

That’s how he got through everything. That’s how anyone gets through anything. Which … yeah. Which is cool. So, yep.