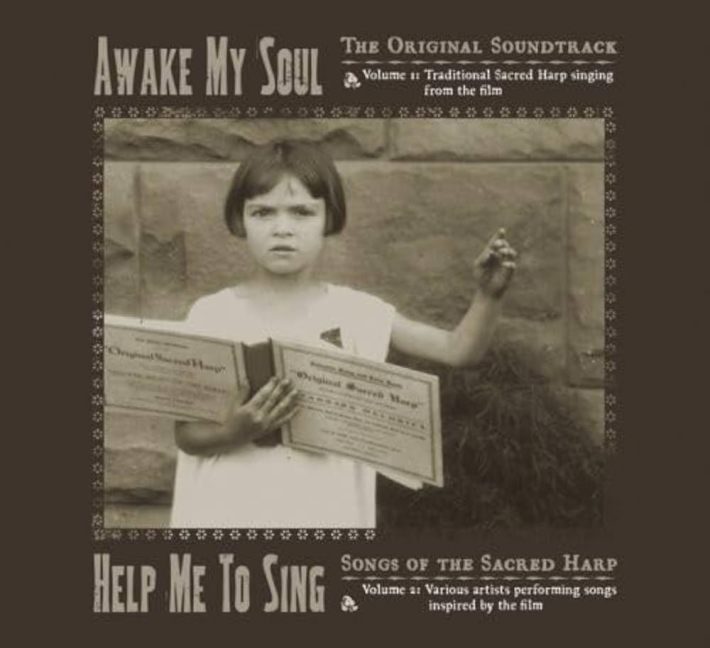

Earlier this week, I found myself in Mineral Wells, Texas, partly as a detour around Dallas gridlock, but mostly on the trail of a singer—this one:

Nearly two decades ago, this photograph, taken in 1930, helped drive a revival of the musical tradition known as Sacred Harp singing. Sacred Harp is one of the oldest forms of American music. For those who know it, it’s much more than history: it’s a means for expression, meditation, restoration, even exhilaration. For me, it’s also an addiction—spanning 12 years, a vast community, and wide swaths of America—that led me on this not-insignificant deviation off of I-35 to look for traces of the girl in this image.

I got home just in time to focus on last-minute preparations for Tulsa’s (Hopefully) First Annual All Day Sacred Harp Singing, which I’m leading on Saturday at The Parish Church of St. Jerome.

Spoiler alert: there is no harp. More on that later. Let’s start with the girl.

***

In 2006, two friends of mine, Matt and Erica Hinton, created an excellent documentary about Sacred Harp called Awake My Soul. They aimed to broaden the music’s audience and attract new singers to this tradition. Naturally, they needed a cover image for the DVD and landed on this photograph.

I find the girl’s expression hard to read. Who was she, and why was her stare so intense? Was she so engrossed in practicing a tune as to be rendered indignant, annoyed by the distracting photographer? Or, had she always been cherrypicked as a Sacred Harp mascot, possessing the same appeal then that Matt and Erica saw over 75 years later?

When the Hintons released Awake My Soul, a whole slew of singers asked these same questions. Amazingly, no living singers could claim her as a relative, even with significant genealogical reach and prowess. As a community, we needed to know who this six-year-old was and why we couldn’t stop staring back.

The only hint was an archival inscription noting its photographer as musicologist George Pullen Jackson, its year (1930), and its location (Mineral Wells, TX). That same year, the late legendary Sacred Harp teacher Tom Denson had visited Mineral Wells to lead a “singing school,” with the goal of bringing the Sacred Harp tradition to North Texas. Armed with all this data, a singer contacted a local librarian, who confidently identified the girl as Lorraine Miles. With her married last name (McFarland) in hand, the address and phone number were easy to find. Matt Hinton apparently rang her up almost immediately to deliver the news of her fame as the poster child for Sacred Harp’s roaring revival, her portrait replicated on small-batch runs of apparel and period media like CDs and DVDs.

According to this account, Lorraine was elated to learn of her new cult status, but also no stranger to celebrity. At Tom Denson’s singing school, she’d won a gold piece designating her as the best child leader that day. Incredibly, that gold piece was her ticket to a feature on a Fort Worth radio program as “Little Lorraine, the Yodeling Schoolgirl.” The segment was so successful the station hired her to broadcast a weekly show, live from Mineral Wells, recorded in the Crazy Water Hotel. Her star shone bright enough to attract talent scouts, but when offered a trip to Hollywood, she turned it down, preferring to complete high school at home. Presumably, her parents had a role in this decision, too.

Despite Lorraine’s lesson, Sacred Harp has boosted no singers to Hollywood since. A cohort was featured on the soundtrack for 2003’s Cold Mountain, but neither fame nor riches ensued. Allegedly, Nicole Kidman didn’t take to it much either. I advise against primitive hymn singing for your American Idol audition.

***

Before moving back to my hometown of Tulsa in 2023, I’d lived in Texas for most of the last decade, mostly in Austin. The city is one I loved, and still do, but more and more it started to feel like a millennial playground. Sick of fashionable country-western cosplay, I craved music and history to ground me—something that pre-dated Willie Nelson.

Miraculously, I didn’t have to look too hard. I’d heard a recording a while before of Sacred Harp, also called shape note singing, and was immediately drawn to its strangeness. As a lifelong choir nerd, I’d grown tired of the perfectionism and refinement required to create a unified sound. Sacred Harp’s rawness was almost rowdy by comparison, and immediately refreshing. Though I’d liked the sound, I left it at that: something surely long past, a curiosity recorded by Alan Lomax and distributed by Smithsonian Folkways.

Still, it stuck with me. Somehow, the presence (or absence) of Sacred Harp singing in a given city became a barometer for whatever I was seeking. So once I landed in Austin, I sought it out.

A Google search for “Sacred Harp singing” and “Austin” took me to a Geocities-era website boasting a church that sang these hymns every Wednesday, located only a few blocks from my Craigslist house. Everyone was welcome to join, said the website. Naturally, I was terrified. But I went—and found myself hooked. I’ve been singing Sacred Harp for over a decade now with communities all over the country, drawn in not just by its harmonies and potluck suppers but by what its stalwarts describe as a “living tradition.”

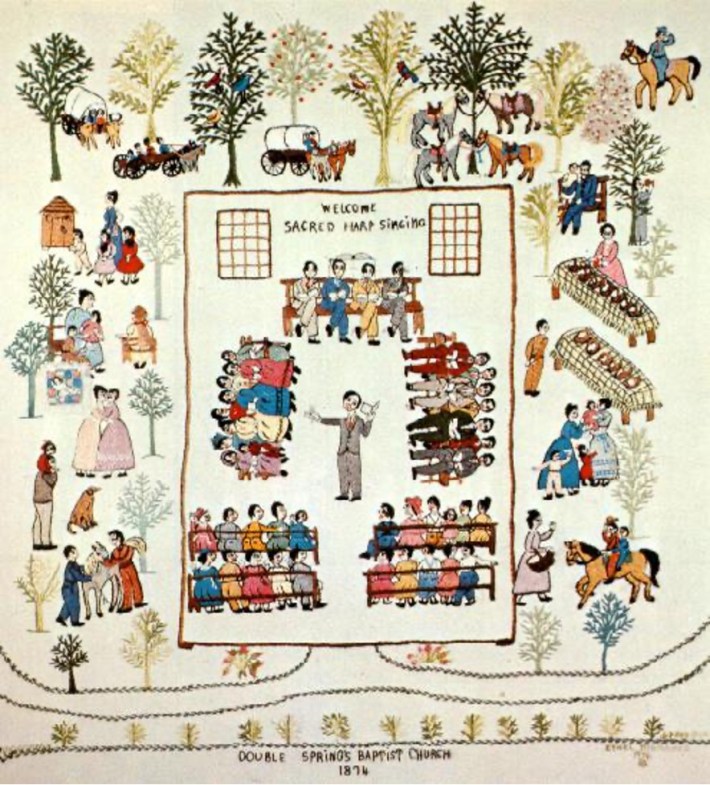

Sacred Harp tunes come to us through a hymnal that was first published in 1844, and they’re sung in a collective, participatory way. A defining trait of Sacred Harp singing is that we sing in a “hollow square” instead of performing outwardly for an audience. This configuration is unique even among church choirs and community choruses.

Singers face one another to create a version of surround sound not unlike The Flaming Lips’ Zaireeka album or The Who’s Quadrophenia. The square’s sides consist of four distinct parts, as in many choirs. The output, though, is something else entirely, a sort of inversion of Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound: imagine Spector’s maniacal layering simplified to its four most potent, dispersed parts, reaching as high as Mariah’s whistle register and as low as Flea’s bass. Somehow, these spare four parts add up to something like a spacious column of sound, a roomy interior instead of a wall.

An Alabama singer, Buell Cobb, described his first time hearing this music in the mid-1960s exactly as I felt it in 2012: “a sustained bolt of lightning.” I’ve been rereading Buell’s writing often since he passed this spring and know he’d encourage me to borrow a few more of his words to elaborate:

Thunderstruck was what I seemed to be.... This was different, in order of magnitude, from finding myself freshly enamored with some new popular song. It was like being rushed into an entirely new realm, and discovering, musically speaking, the sturdiest architecture … resplendent trappings.... As thoroughly old-fashioned as I realized this music to be, it seemed fashioned, in the moment, somehow specifically, majestically for me. It was like coming home—and in the most resounding way—when I hadn’t realized I had been away.

I too walked into a lightning field the first time I sang this music, an experience far more distinctive than listening to the recordings. Experienced in real time, the open harmonies and hefty lyricism were more than I could take in, like an Ansel Adams photograph shot at a higher resolution than the human eye can see. Tom Denson would prophetically warn novice singers, “If you stay here, it’s going to get ahold of you, and you can’t get away.”

I quote Denson as if he’s passed recently, like Buell, yet he’s been gone since 1935. To me, the 90 years between then and now is a chasm, his life lived so long ago I can only imagine it via historic hints. 1935 was the year FDR first signed the Works Progress Administration into law, the year Babe Ruth hit his last homer, the year Elvis was born.

That 90 years dramatically shrunk for me when I heard Tom’s words quoted by San Antonio singer Mike Hinton, who attributed them to Pappy Denson, his granddad. I’d sung with Mike for at least five years by then but was somehow still oblivious to the lineage. This type of epiphany is far from uncommon among singers. Sacred Harp is a place where memory and history are inextricably bound.

***

Hoping to find traces of Sacred Harp on my recent trip through North Texas, I’d checked into the Crazy Water Hotel in Mineral Wells knowing only a bit about its story. The 1927 building had once seemed destined for decay. After closing in 2010, the building’s terminal diagnosis seemed irreversible until a late-career investor moved home and compelled 88 other locals to co-invest in its restoration. In 2021, the hotel re-opened and began marketing to sentimental suckers like me to check it out.

Mineral Wells first got on my radar a few years back through a friend’s description of its lost grandeur. It’s a small city—with vibes similar to Arkansas’ early 20th century hydrotherapy mecca, Hot Springs—whose "crazy water" allegedly soothed a range of ailments. Word got out, and the springs sprang luxurious lodgings, coaxing the unwell to its wells. In the end, modern medicine would remove Mineral Springs from the map. Still, the architectural footprint remains.

Even before learning its lore of healing waters, I’d seen the town’s name in one of our Sacred Harp hymnals. Our tune book will sometimes note the birthplace of a hymn’s composer; because I found Sacred Harp in pursuit of regional music, those place names tend to stick with me. Many of the most hallowed singing spots have no named location at all, just latitude and longitude coordinates. Singers of an advanced age will still offer rambling, folksy directions to these places. (“Go a mile and a quarter after the first exit, then it’s the second left from there. Not the dirt road though.”)

I’d also read about Mineral Wells in an excerpt from historian George Pullen Jackson’s White Spirituals in Southern Uplands that described his experience at the singing school Tom Denson led there in 1930. Historically, well-steeped singers would travel as instructors to places with only a few singers, aiming to bolster and grow those communities.

Despite Denson’s efforts and my years of singing in Texas, I’d never encountered anyone from the Mineral Wells area through Sacred Harp. The portrait of that young girl was the compelling draw for my visit, but I was also excited to check out some new territory, even if singing had long since faded there. I even held some underlying hopes of discovering musical ties between that region and my own. An academic who’s extensively researched and mapped Sacred Harp’s geography has more or less designated Oklahoma as a desert, a conclusion I refuse to accept. Even if this geography never encompassed Oklahoma historically, the nature of a living tradition means that that jury is still out.

In that sense, since Tom Denson seemingly never made it north of the Red River, this Saturday’s All Day Singing in Tulsa is an attempt to bring Sacred Harp to my hometown, much in the spirit of the old singing schools.

***

The Sacred Harp singing community is close knit, but as dispersed geographically as the harmonies we sing. I seized this Mineral Wells hotel happenstance as an opportunity to get in touch with Matt Hinton. He lives in Georgia, and we sing together only infrequently these days. He instantly replied with ”pics or it didn’t happen”—then shared this photo from the 1930 singing school where Lorraine struck gold.

Lorraine’s cover girl portrait was shot against this very building. Thanks to a kind hotel employee whom I almost certainly overwhelmed, I located the site of this photograph. The Convention Hall depicted is long demolished, but it was located just two blocks north of the Crazy Water Hotel. Unabashedly unchill about both Sacred Harp history and architectural heritage, I knew I’d be elated by any and all archaeological findings. With daylight fading, I bolted to the site, eager for any traces that remained.

The literal foundation was still there, but not much more:

I hesitated to take a piece of the foundation’s stone; it felt akin to taking fossils from a National Park. Five seconds later I got over that, grabbed a loose, sensibly sized piece of Lorraine’s backdrop, and rushed back to the hotel. I sent my unremarkable photos to Matt, gloating, reveling, and offering the rock as a bargaining chip if the Hintons visit Tulsa for 2026’s Second Annual All Day Singing.

This is Erica Hinton and her daughter, Anna, when they got the chance to sing with Lorraine in 2012. At 89, Lorraine was apparently sprightly, sharp, and charismatic. I’m sad I never got the same chance. This is my ultimate FOMO—something I’ve often felt when introduced to past Sacred Harp legends through stories and writings like Buell Cobb’s.

In four decades, I’ll be the soppy elder looking back at photos from my own early singing days. Already, they feel distant. It’s an unflattering archive, mostly shot at strange angles from within the hollow square. I like this one of me and Anna from 2017, though. We’re shown leading a song together in Henagar, Alabama, arguably the Sacred Harp mother church, and a place I know I’ll revisit many times in the remaining years I’m granted.

In any other setting, such a forecast would feel aspirational, or maybe even arrogant. Who am I to predict what will happen next year, let alone 40 years from now? Affirmed by my memories of other singers who have stood there too, leading songs with others who arrived even earlier, I have no doubt it’s true.

***

If Sacred Harp is indeed a living tradition, I’m made uncomfortable by the histories that freeze it in time. Accounts like George Pullen Jackson’s are not inaccurate, but they portray this musical practice as declining, emblematic of an era that’s already ended. Reading these accounts, it would be reasonable to guess that the “old ways” have already disappeared. That was my original assumption, after all, one I’m very grateful was wrong.

Every so often, a public radio station or local paper picks up on our curious singing thing. A common narrative is that hip urbanites are taking the reins to revitalize Sacred Harp singing. There’s something there, but ultimately age is agnostic. New singers are warmly welcomed, even if it’s because we love fresh blood and know it’s needed for this tradition to live on.

What I particularly don’t like about these takes is their implied binary between young and old, rural and urban, believers and non-believers. To me, such characterizations are embarrassingly reductive, readily complicated by any Sacred Harp singer’s lived experience. Yes, we are an unlikely bunch. As singers, we don’t agree on everything. Political discussions are outright discouraged. Still, we always manage to get along, largely because anyone with a love for these songs belongs.

Even with Sacred Harp’s overtly religious lyrics, the hollow square is an inclusive space for anyone drawn to its music. Primitive Baptist elders will share a church pew with dreaded hippie Vermonters; turns out, they’re all farmers. I’ve known many queer singers that are drawn to Sacred Harp as a way to reconnect or reclaim religious upbringings that chided alternative gender and sexual identities.

My own faith journey is similarly fractured. Singing has mended it; still, I’m unsure what it may mean to feel whole. When I found Sacred Harp, I hadn’t attended church for years. Some Sacred Harp hymns are familiar, reminiscent. Others feature theology so fearful that it seems to resonate from a place of utter existential uncertainty, regardless of how God fits into the equation.

Many older tunes grapple with a life that was “ever on the wing” when “death [was] ever nigh.” Medicine has improved since they were written, but it only prolongs the same ending. Death is often an avoided topic, or even something to cheat, but our Sacred Harp community confronts it head on, sometimes even shouting these words in our singing. I think this willingness to greet death is what connects even the most dissimilar singers, and by singers I mean friends. One of the most frequently sung hymns encapsulates it perfectly:

Give joy or grief, give ease or pain

Take life or friends away

But let me find them all again

In that eternal day

Our current historic moment is one of polarization and loneliness. Hope feels like a word from a distant vocabulary. A prescient hymn asks, “Lord, while we see whole nations die / Our flesh and sense repine and cry / Must death forever rage and reign / Or hast Thou made mankind in vain?” Amidst it all, music is a rare shot at mutual understanding, maybe even acceptance and restoration.

Whether you find that possibility intriguing, preposterous, or hopeful, I invite you to check out Tulsa’s (Hopefully) First Annual All Day Sacred Harp Singing. No music experience is needed, and all are welcome. You might hate how it sounds. But for those that don’t, beware: “If you stay here, it’s going to get ahold of you, and you can’t get away.”