American Artists, American Stories

Philbrook Museum of Art

Through December 29, 2024

When people talk about being American, they’re inevitably talking about the flavor of American that they themselves are. Being an American is different for the recently-arrived Hmong mother of two than it is for the white suburban housewife whose British ancestors colonized Native land. So much is America the melting pot it claims to be that to say “American” tends to beg several qualifiers of description.

Philbrook’s swaggering, massive exhibition “American Artists, American Stories”—a title as broad and cumbersome as the country it seeks to emulate—takes on this challenge with a wild resolve, more success than failure, and a few curatorial befuddlements. I left both proud of and excited about the American project and disappointed by the pigeonhole into which the word “American” is so often forced.

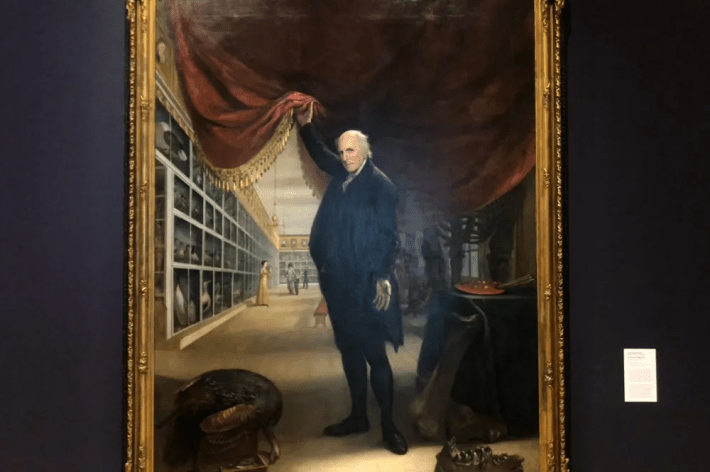

The imposing and irresistible “The Artist in His Museum” by Charles Wilson Peale (1741-1827) greets the visitor first. It’s a suggestive opening. What curiosities will we see inside, and what violence is insinuated by the comparison of America to a treasury of historical specimens? The show is drawn from the collection of the Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), an early nineteenth century project of Peale’s own founding that sought to “promote the young country’s burgeoning artistic identity.” That early identity was unsurprisingly white and male.

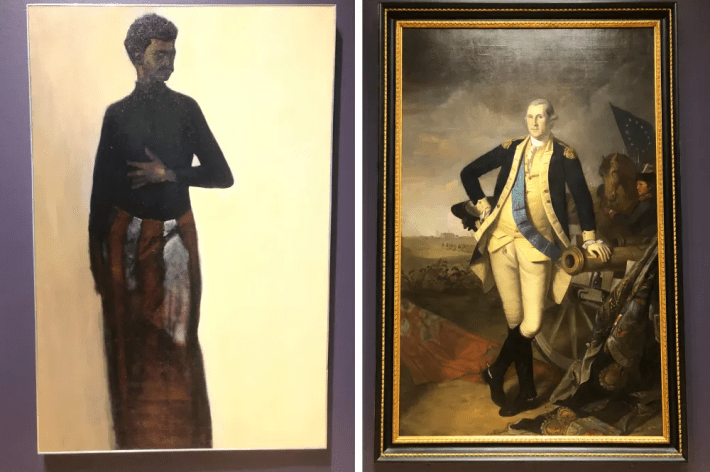

As time went on, however, the institution began collecting the art of women and Black artists. The dynamic of white and Black is a bell rung often in the first half of “American Artists, American Stories”—to the exclusion, across the show, of artists of Native, Asian, or Latino descent, an exclusion which the text of the exhibit, admiringly enough, admits. It sets early Black works next to early white works and allows the viewer to consider the uneven power dynamics inherent in those early relationships. One of the more visceral moments comes from a side-by-side pair of portraits: Peale’s portrait of George Washington next to James Brantley’s (b. 1945) “Brother James,” a sober self-portrait that drapes the Black artist and veteran of Vietnam in the colors of a subdued American flag. In Peale’s portrait of Washington there features, at the President’s side, one of his purchased slaves.

The salon wall that appears halfway through the show blossoms in a fervor of styles, swapping the earlier concerns with identity and history with those of beauty and technique. It’s pleasing, but I was frustrated by a few choices. The choice to include no explanatory material on many of the artists spoke to me of imbalanced curatorial priorities on the part of PAFA, who put the show together. Milton Avery, for instance, one of the seminal artists of American abstractionism, gets zero words.

And why does this crowd not deserve, for example, to learn about the early Modernist and WPA artist Stuart Davis, whose only extra-biographical material asks children what song his work makes them think of? This is not necessarily a fault of Philbrook, which is only showing the exhibition, not writing the bulk of the material for it. And yet, to me, these omissions seem to rebut the grandiosity and the fullness that the show professes to espouse.

Overall, “American Artists, American Stories” successfully offers many towering works from the American canon: it’s worth savoring and revisiting. The diversity of art with which America expresses itself is only hinted at here, and yet even in that hinting it achieves much. The flower of national pride tends to grow into a weed in American soil, but while walking this show, I experienced a certain admiration: for who we are, and how many ways we are, and what we’ve come through, and why it matters. But please, once you’re done in this show, walk a few hundred feet and see some of Philbrook’s incredible Native art, as a corrective measure.

The Pickup's reviews are published with support from The Online Journalism Project.