Editor’s Note: Matthew Phipps came of age in Tulsa and has traveled the world as a photographer and curator. (Back in 2012, This Land Press captured him filming a skate video in downtown Tulsa for an episode of True Tulsa.) He has been based in Mexico City for the past six years. He’s recently published a new book of photography, Heart and Soul, that documents his grandparents and more importantly his adventures with his grandfather, who battled dementia during the last 10 years of his life. In this essay, Phipps shares a handful of those photos and the stories that surround them.

For 10 years I traveled without stopping for more than three months in each place, but I made it a point to come home to Oklahoma to see my family regularly. Family has always been important to me. I am adopted, but the family that raised me has been a continual blessing my entire life, so each time I was home, I tried to spend as much time as possible with my grandparents, William and Velma Phipps, because I knew the clock was ticking.

Both of my paternal grandparents grew up in Okmulgee, although my grandmother was born along the Sand Springs trolley line somewhere around 65th Street West. They married before World War II and then my grandpa was sent to Fort Bliss and later to Hawaii. He was preparing for the invasion of Japan before the atomic massacres occurred. Luckily he never saw combat. During the war, my grandmother went to live with her sisters in Wichita, KS. After the war ended, they lived for a couple years in Muskogee, then for more than 50 years in Oklahoma City. They moved to Tulsa in 1995 to be closer to the grandkids.

My grandparents were like a second set of parents to me. They lived a mile down the road from us in Broken Arrow and were constantly present. Their style and grace has been a big factor in the way I dress and conduct myself on a daily basis. They were classy, yet not fancy. This helped shape the way I see the world and the morals and values I have in my head and heart.

Things changed as they aged. My grandmother had kidney failure and stayed on dialysis for six years. In 2015, she called me when I was in Warsaw, Poland, and told me it was time for her to go. I flew home and held her hand while she passed, then played a salsa song about life being a carnival and danced around her body.

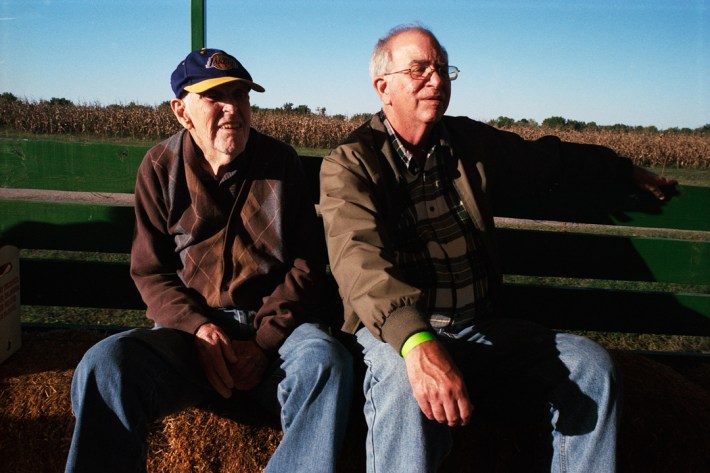

Seeing Grampy's reaction to his wife's death made me want to help keep him active as we both tried to outrun the sadness. Over the next three years, every time I would come into town, my grandpa would come with me on daily adventures. I would take him to meetings, out on dates, and to concerts or jazz nights. You can ask Mary Beth Babcock about Grampy falling asleep in the display window at the old Dwelling Spaces in Tulsa’s Blue Dome District.

We would go to the Gathering Place, for a drive through the Osage Hills, or maybe down to Okmulgee to visit Grammy at the cemetery. We always took backroads, making pit stops for photos and having lots of laughs. Grampy would frequently say “I don’t know where I am, but I sure am enjoying myself!” even if we were on a road that he had traveled down hundreds of times before. The thrill of the known unknown was spectacular for him and he was in awe of the world and its wonders.

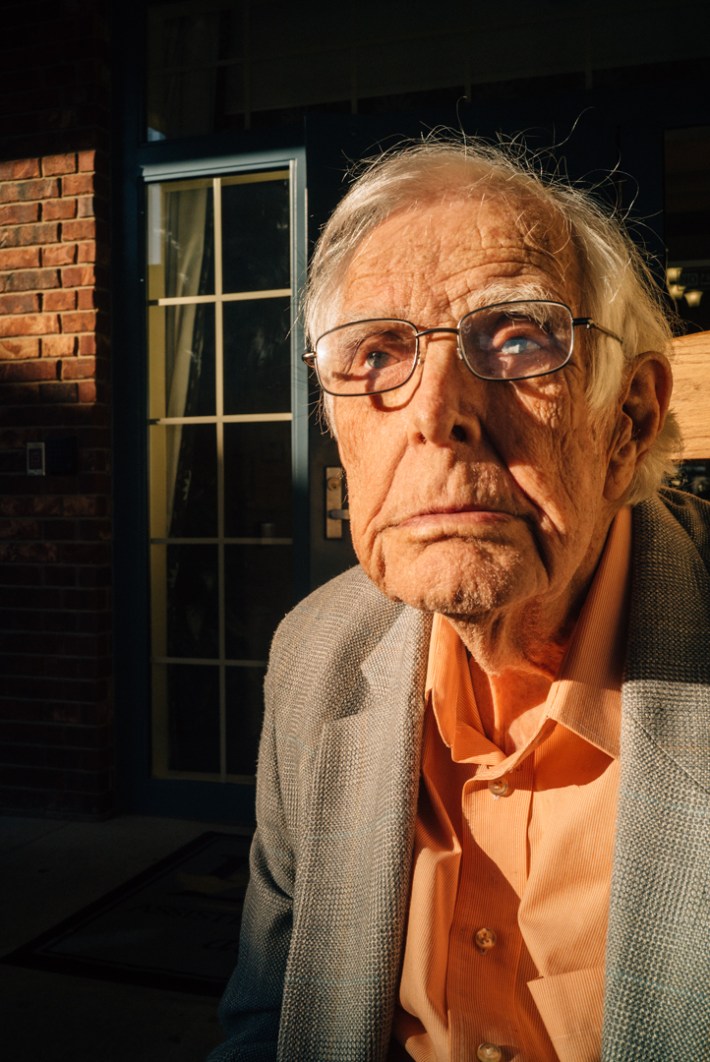

Grampy lived life five minutes at a time during his last years. His long term memory worked pretty well, but he couldn't tell you what he had done yesterday or the day before that. I think he was pretty confused in his head, but was able to project a wonder and a sense of excitement to the outside world that was visible on his face.

One day on an adventure to the Gathering Place, I wanted to push Grampy all the way down to the river so he could touch the flow. It was October 2018, the river was flooding, and threats of the levees breaking had everyone on edge. Somewhere along the trail, we lost his glasses. That night, Grampy fell on his way to the bathroom. I found him the next morning in his bed with a broken rib and a punctured lung. We called the ambulance and got him to the hospital.

The next day I had a flight for a trip to Mexico City, Barcelona, and then Athens, so I asked Grampy what I should do. He told me to go, adding “Make sure you take lots of pictures.” He always said this to me when I departed for any of my trips.

I was in Athens to shoot the 10-year anniversary of the death of a young anarchist in the Excharhia neighborhood. I shot a photo of a guy throwing a Molotov cocktail at the police. The image would become the cover of the first edition of my book Every Day Is Babylon. Right after I shot the photo, I got smacked by four or five rubber bullets while three cans of tear gas plopped down in front of my feet. I had to spit in my hand and wipe my eyes to retreat to the anarchist base, where a woman sprayed my face with Milk of Magnesia to relieve my pain.

When I got home from this event, my mother called me with the news that Grampy was being admitted to hospice. I caught a flight the next day and flew 14 hours from Istanbul to Houston in order to get there for Grampy.

I spent 11 days with him in hospice. During our time together, I photographed and interviewed him. He told me about his trip to Mexico City in the 1940s—a story I had never heard before—and other revelations as well. It was as if his dementia lifted and his old memories were clearer than ever.

As Grampy passed, I played Johnny Cash’s “Ghost Riders In The Sky” and gave my salutes with my dad. My grandfather's life and death are some of the most inspirational things I have witnessed in my almost 40 years on the earth.

Thank you Grammy and Grampy. Your life lessons live on in my life and work every day.