In late May 2020, after George Floyd was murdered, Tulsa-based photographer Joseph Rushmore traveled to Minneapolis with his camera. After the June 2020 Trump rally in Tulsa, he drove to Portland's Black Lives Matter protests in July, sleeping in his car, shooting photos at night, and enduring physical assault alongside protestors and other journalists. And just this year, he stood right in the middle of the violence at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. He wasn't on assignment for any of these events—he just made the decision to go, and his photographs of the time exist in a space between documentation and art that he's still trying to map.

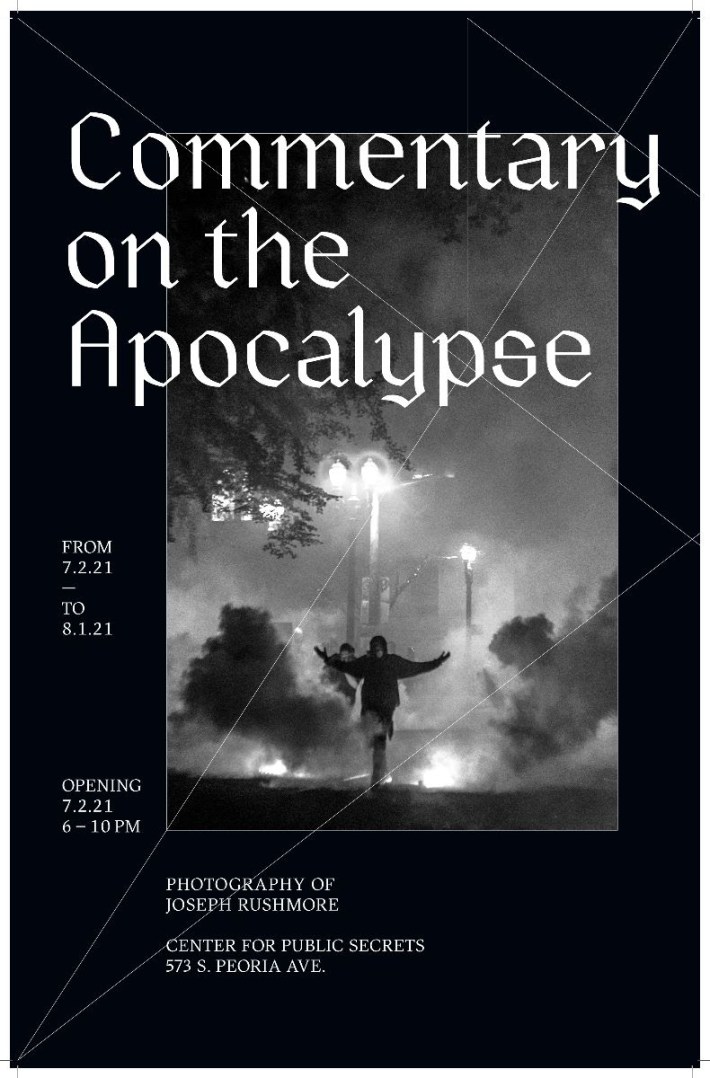

Rushmore has been photographing protests for years, from the Oklahoma teacher walkout to Standing Rock, where he says he learned a lot about the ethics of documenting a community. He built "Commentary on the Apocalypse," his first solo show, to live inside the rough, exposed brick and industrial grit of the Center for Public Secrets, where it will remain on view through August 1. (You can hear Rushmore talk about the exhibit, in conversation with his frequent collaborator Liz Blood, at the Center on July 24 at 5:30pm.) He described some of the pieces as not quite sure of themselves, or on the way to what they want to be, or otherwise in progress, imperfect, getting there.

A native of Ada, Oklahoma, Rushmore the artist tends to speak about himself in a similar manner. He's comfortable discussing his questions and doubts and worries, with little need to pump anything up (least of all his own choices) or project art-professional confidence. These times can be chaotic, broken inside, somewhere between reality and nightmare—and because he allows his work to communicate that too, he's one of the most essential, incisive, emotionally rigorous photographers working today.

Rushmore spoke with me on location at the CFPS. He wore a t-shirt that showed a cartoon of a cowboy boot kicking a swastika, underneath the words "Our Kind of Country," which got nicely to the point.

Alicia Chesser: Can you tell me about how this work and this show came about?

Joe Rushmore: Sometime in the summer of 2020 was the first time I started really having trouble figuring out how to document the things I was seeing. I didn't have words to describe what it's like to see the police in Minneapolis abandon their precinct, and then to watch it burn. And then the next night it was something crazier and crazier. What I was seeing was very grounded in reality—watching the precinct burn was a very real and tangible thing that I completely understood—but I could not quite understand how to describe it.

I got to Portland on July 25th or so. We'd had the Trump rally here by then. By that point, the uprisings had been going on for almost two months. Portland was just an incredibly surreal experience, as opposed to this thing of "we're going to burn this place down because a murderer came from here." I think it was just as called for. I don't take issue with any tactic used to fight the state. It felt right to me, but it was so real and so indescribable at the same time. And so I started looking at how to make photographs that were a little more ... I mean, it was like a nightmare acid trip circus every night.

The Minneapolis work is fairly straight documentary. Then in Portland you see the beginning of this shift in how the imagery presents itself. In terms of this show, the timeline ends on January 6, 2021. About that time, I started realizing that I had so many images of so many things that were happening that were changing America and the world that eventually I would need to start thinking of how to put these images out. They were just going onto Instagram at the time. Whenever I thought about a show, I knew right away that it would not be something where I could just put a frame around some photos. For these, I wanted to see that barrier taken down.

People would say to me, "You've seen so many crazy things, been to so many of these crazy places, it's like history is changing and you're there." And in my mind, you or anyone else was there just as much as me. I think everyone felt everything happening in 2020 so deeply and so personally. Maybe I was there physically, but I don't think I was experiencing it more deeply than anybody else.

I wanted very little barrier between the viewer who also experienced all these things and the images. So I started thinking about presenting them on a larger scale. First, to get you out of the phone completely, which is where my images usually live. (I never see them outside of my computer, which is a 13-inch screen.) And second, I wanted to print some of them on printer paper, card stock, with a laser printer or an office printer, whatever I had lying around, and collage them all together. Photo paper does a very specific thing. It's a foreign thing that none of us, myself included, are used to handling or feeling or touching. But we all know what printer paper and laser ink feel like in our hand. When I walked in here, I was like, oh, these pictures look like they could've been printed at my house. Even if subconsciously, the viewer is able to understand what your fingers would feel if you were to reach out and touch it.

So every bit of this was an attempt to take a barrier down. I attached them to doors, cabinets, whatever I could get, reused wood. The wood's not really cut; I tried to use as few tools as possible. I had a $10 drill that I bought at a pawn shop. I tried to make everything come down to: can somebody else do this as easily as I can? I'm doing this in my apartment with very little money, very little resources. Can you also do that? That was another barrier to take down.

AC: Do you think, in the not too distant future, a lot of us might be called upon to do this kind of documentation, as things begin to get more apocalyptic?

JR: Think about how hard it was to keep up with the evidence of atrocities in the summer of 2020. Think about how hard it was to remember what happened. Was that in Atlanta? Was that in Detroit? You go back and look, and you'll see something that barely made a blip on the radar that any normal time would have been massive news, you know? Think about how important documentation is then. While something that happened in Denver may have been a blip on my radar, it was monumental to a community in Denver. I don't have documentation of the thing that happened there, but somebody does, and their community then is going to need the means to convey and see and soak up that fact together. And as you said, to get it out of the phone and bring it into real life, to live with it in real life, which is the place where it actually happened.

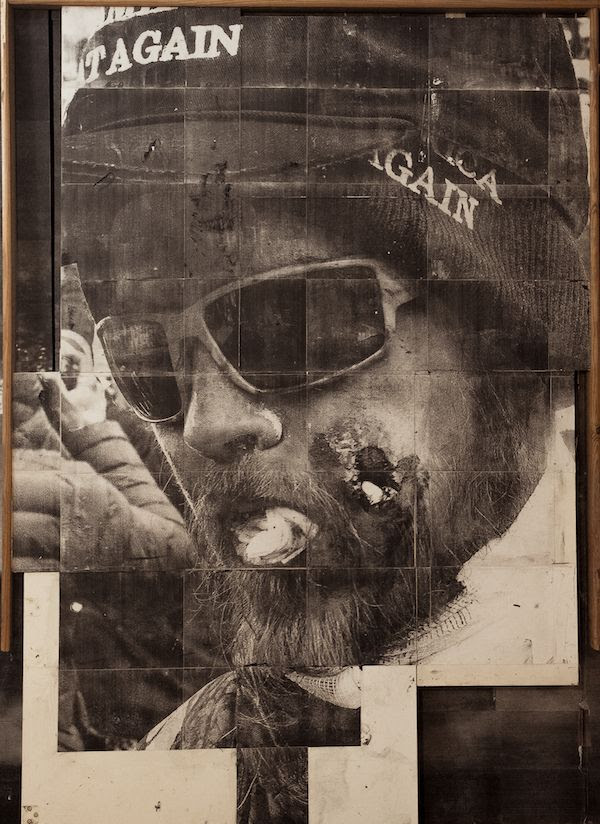

I wanted to bring these out of that social media space at least for some period of time. And I also wanted to live with them. This entire show is an experiment. It's me trying to figure out how to bring these things into physical space. When I started bringing them out, I started realizing I've got sort of these two sections: one section, essentially half the room, is Black Lives Matter protests, and one is far-right extremists. There's a very obvious, specific delineation between these two things, right? As I was working, printing these off, glueing them to the boards, scraping the images, distressing them, I started feeling like there needed to be a difference in the weight I was giving to the far-right work and the work on the Black Lives Matter protests.

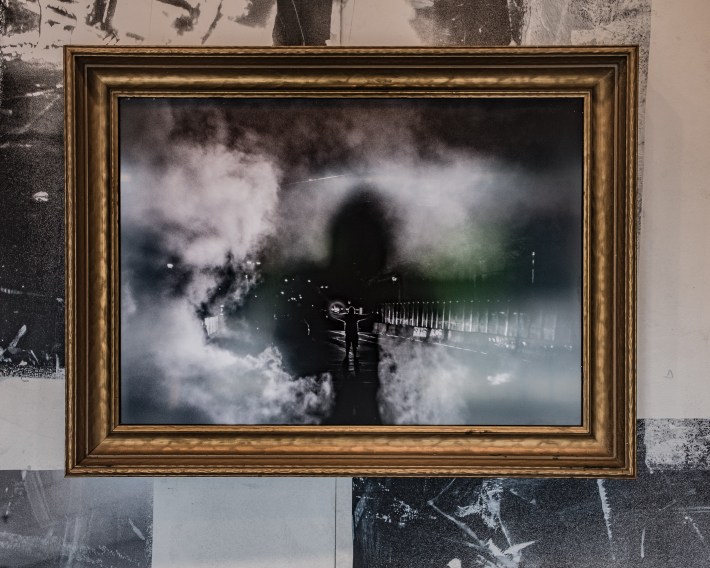

The third precinct in Minneapolis was a place of terror for a community and that community came forward and shut it down and it's still closed to this day. To me, those photographs are deserving of respect because I respect what's happening there. I'm not sure what I'm going to do going forward with the physicality of the work. Where I settled on for now was, well, I'm going to offer these more respect. That's why there are those few that are in frames.

AC: When you start to incorporate this kind of three-dimensionality, almost a theatrical or installation aspect, so it's no longer just a 2D surface, the work takes on a lot of meanings and picks up a lot of other ideas along the way.

JR: I kind of started learning that halfway through. And I had to find a workaround that I think is imperfect right now, that I'm going to keep searching and working towards, because I think putting these few photos in frames is a pretty simple, simplistic answer to this uncomfortable feeling I had. I was uncomfortable that things that seemed to hold something of evil held the same weight as something good. And my answer was to be very direct and say, well, this is the thing I respect, which I think is already pretty inherently known in the work. I don't think a lot of people are going to come in here and be confused thinking that I'm, like, excited about the Trump rally. So this is the answer that I came up with. I think it's on the way to figuring something out.

Whitney Chapman, who helps run the Center for Public Secrets, approached me around the beginning of May about doing a show in this space. I said no. She kind of talked me into it by just being like, well, the space is yours, you can do whatever you want here, and that kind of pressured me to do this thing I'd had in my mind for a long time, to do it in this physical way. I had two months to do it. It was sort of like a spasm, like this short eruption of work that ended up with this. The work is still open to moving and shifting and being whatever else it needs to be. This is not the end of it. This is me just now.

AC: I think there's a lot to be said for those pushed-off-the-cliff times, if you're struggling to conceptualize what you want something to be. There's such a tendency to overthink. Sometimes what comes out on a real quick deadline is a lot more authentic to the actual core of what you're going for.

JR: I grew up in DIY music and it was never even a consideration of whether you were ready to start playing shows live or not. Did you write one song? Okay. And so you put this imperfect thing on stage, and oftentimes that is what leads you towards what you're supposed to do. In my mind this is a similar sort of ethos to what I grew up with musically: oh, did you take a photograph? Okay. Put it on the wall. Right. And as you were saying earlier, it's certainly an encouragement or a provocation to anybody who comes in here who's like, well, I saw some stuff too. Maybe I should be putting pictures on a wall. Maybe I should be trying that.

Obviously we need photographers for the news there every night. We need to know what happened. We have to have that very tangible stream of information. We have a lot of those people and they do excellent jobs—and I'm not one of those people. And so it's like, well, do I have a place here? I couldn't describe with words what I was seeing in Minneapolis. The visuals, mine included, from that night didn't seem to describe what it was, what it felt like. And so I decided that I wanted to try and figure out a way to accurately describe the emotion of the things that were happening. The emotional landscape, if that's the right term. I had this realization that eventually we would be looking back at what had happened. At that moment we were in the midst of it. It was happening to us. It was a current occasion. Eventually we would have to find ways to understand while looking back.

And I feel that the best ways that I've been able to understand, looking back through history that I was not a part of—oftentimes poets are the best people to do that. They have all these ways to put you in that place. At some point we will need poetry to tell us what happened. And I wanted my photographs to fit as closely to that as possible. Eventually we will need to talk about this with poetry, and the photograph can be a poem. That's what I searched for.

AC: Can you take me to a couple of the photos that get close to doing what you're describing?

JR: When I got to Portland, I was completely unable to capture what I was seeing. I put out very few photos in those first couple of days, because the things I was seeing were so overwhelming and it took me a while to just learn how to exist in that environment. Around the third day I was there, in this entire two or three block area around the courthouse starting around 11 or 12 at night, things would start going up for the next three or four hours and the entire area would be in this constant fog of tear gas. It was like walking through fog everywhere you went. It was inescapable. I had a really good gas mask, so I was able to just exist in this weird fog nightmare dreamscape. And it was overwhelming because there was so much color: street lights, fog, police lights shining through it.

I was not able to figure out how to do it in black and white, because the colors were a psychedelic nightmare. Around the third day I kind of started figuring it out. And I made "Teargas Angel," which is the man with his arms outstretched. This is the federal courthouse. This is the police line. And they're shining a huge spotlight on him and he's begging and we're standing in a cloud of tear gas. That's a shadow on the cloud, essentially. This is a religious image. I mean, there's the obvious Christ pose religiosity of it, but it's also a man actually sacrificing himself. He's standing there alone. The police were shooting projectiles at us; they shot him right after this. Visually, it doesn't really give you information. You don't know where this is. You don't know what's going on. This image helped me describe what it feels like when you strip the context away. And it's the first image I made last year where I intentionally set out to not describe the scene that I was seeing in front of me, but to describe what it felt like to be there.

AC: Tell me about this one, about the fabric you've incorporated here.

JR: This is one of those experimental works. So the image is of this man, he's like the Grim Reaper, right? He's got this full mask on and skeleton gloves and he's got a black hood over his head and he's holding a Bible in his arms. This was on the steps of the Capitol, in the first five minutes that things started happening. The melee was just beginning, people were starting to hit the police line right there beneath the rotunda, some scuffles were starting. I was going up these little stairs and this man was in front of me and he turned with his back to the Capitol, looking towards the Washington Monument. He had this death mask on and he raised his arms out. I took one photo of him with his arms outstretched. Then from over my shoulder, somebody reached forward with a Bible and handed it to him and he grabbed it and clutched it to him. And I took one photo of that, and continued moving.

It's a really super haunted image to me. So I decided to cover it. I've been playing around with veiling and using fabric for some time in different ways. This is not at all what I want it to end up as, but it's what it is for now. What needs to happen is I need to learn more about death shrouds, funeral coverings, and things like that. I need to know more, which I didn't have the time for this time. So this is sort of a placeholder.

AC: It's almost like you've set a boundary with the fabric, too, the way it spills out into the space. It's really nice to not feel like I have to get close to that, that I can stay back. Or it's like a piece of ectoplasm sliming down from the image, like some sort of extrusion or trail. The fabric is so delicate, but it has all these other connotations as well.

JR: I think you're onto something for sure. It's so good to talk about it. So much of what you do as an artist you do on your own and you don't know exactly why you do it. It's good for someone to be like, well, this is what I see. To be honest, this was originally supposed to be a projection, but I couldn't make it work. I was freaking out at the end to get something up. And it turned into definitely the most sculptural of all the pieces in the show.

That moment in my life was and still is one of the most crystalline moments I've ever had. It was like a spiritual moment, but it felt like a curse. Because there's something so deeply satisfied about the smile on his face and his body language. (That's not even getting into how pop culture affects and is used by the far right. Not so much on the meme level, but more like iconic imagery.) I don't know if you've had this experience, but it's that moment 45 minutes after you drop acid and you're like, oh, there's no turning back. This is actually real. Even if I've done this before, it's always different. It's always scary. And I'm like, oh, I can't get out of this now. That's the moment that this occurred. I'm just immensely haunted by it. It's also something I hold special and close to me. Out of all the insanity that happened to me at the Capitol and to everybody there, this probably sticks with me more than any other, because it was such a perfect description of everything I see in the far right.

AC: When I saw this next one, at the opening of this show earlier this month, I'll be honest with you: it was the first time I was really able to feel the totality of all the emotions of the past year, all at once. What am I looking at here?

JR: In the fall or winter of 2020 Governor Stitt announced that there would be a COVID prayer day. After doing nothing at all, that was how we were going to solve it. Liz Blood and I started talking about maybe doing a zine focused on what that meant. [Blood, Rushmore, and ten writers recently produced a zine on newsprint called "I'll Take You There" about the 2020 uprisings against police violence.] Then I went up to the Capitol on January 6th. It was incredibly traumatic, incredibly violent. I came back feeling pretty fucked up and having to quarantine for two or three weeks, alone with my mind, which at that time was the worst place I could be. I would take drives around Northeastern Oklahoma, go find back roads just as a way to get out. I'd find a lake and go walk around it. And as I was doing that in middle and late January, I was also thinking about prayer a lot. What is prayer? What is it used for? And in my own personal life, what do I feel like it is?

So as I was driving around, I'd take pictures: the deer somebody had killed and gutted, trees, water. The piece is these things intermixed with scenes from January 6th in the Capitol. Whenever I was walking around these woods I would think about how incredibly presumptuous it was for our leaders and the Christian far right to have the audacity to claim prayer as something of their own. I would see a rock and would just know, like, they never prayed for the dirt below this rock. This rock deserves a prayer, this dirt underneath it, this stick, that wave that just hit the shore. And if we are not going to pray for all these things and treat them all with the same level of respect, how do we have the audacity to think that we can pray for COVID to stop or whatever it was that he wanted to happen with that particular prayer day? If prayer is going to be something that we are to use, which I think is a perfectly acceptable thing to be a part of a person's life—it is oftentimes a part of mine in some strange way—then we need to treat it with way more respect.

So this is called "All the Places a Prayer Could Never Touch," because it was obviously impossible to pray for every one of these things. I could never do it. Looking at it as I built it, it became incredibly obvious to me that, oh, this is just a picture of my brain in January 2021. My brain was nothing but anger, darkness, and just replays of the Capitol for months on end. I was already wanting to do some therapy because of all the violence I'd experienced in the summer, but the Capitol was just unbelievably more violent and more evil than everything else. I was very lucky to receive a grant from the IWMF [International Women's Media Foundation] to help with the cost of some pretty intensive therapy for a few months. That helped tremendously. After last year they opened up funding to any gender because they were like, you know, we know people need help. This is what it looked like in my head: a pretty bad place to be. Again, the piece is an attempt to show not necessarily what happened at the Capitol, but to show what it felt like. And I hope this is a pretty solid representation.

AC: Thanks for taking us inside all of this, Joe. It really is a pleasure to talk with you about this stuff.

JR: I'm self-conscious about talking about my own self in an artistic way. But I realized that whenever I find a new photographer or painter or whatever, it's 10 minutes before I'm looking up an interview with them. Like, it doesn't take long for me to be itching to have them tell me about their work. I love whenever other people do it. So I want people to appreciate my art in a way that I appreciate those artists. Talking about it opens me up and improves my work and helps contextualize it. I realize now that I cannot just, as I would like to do, let these live in a vacuum. I put very deliberate actions into creating this, and that context needs to be there because not everything can be unspoken.

I had this teacher in high school. One day he went down to the basement and got the darkroom equipment from the '70s, and he set it up in the closet in the art room and he's like, I know the very basics. Here's how you develop film. Here's how you turn this thing on. Here's some books. This is your art now. You're not gonna do any of your dumb little paintings and stuff anymore that you do to waste time in my class. (I was creative and he could see that, but I was also just fucking off all the time.) He's like, you're not going to do any of that bullshit. This is what you do now. Sit in this closet all day. If you want to leave school and go take pictures, go do that.

So I started doing landscapes. That's all I wanted to take pictures of. When I got to college—I did like two semesters of community college—there was this teacher there who was like, let's talk about what you're doing with these landscapes. And I was like, well, sometimes I just want to take a picture of a flower. And she said: "You have never 'just taken a picture of a flower.' Why do you hate there being people in your photographs? Good. Explore that. That's part of your landscape." She was so instrumental.

I think about that all the time. Whenever I say I don't like talking about my art, what I'm really saying is that I'm uncomfortable talking to people. Actually talking about the art is something I deeply love.