On the morning of September 19th, a 40-year-old single mother was on her regular route, dropping off her four kids at school when she noticed an unmarked Nissan following her from the drop-off line.

The vehicle continued to follow her from a Tulsa elementary school, then a middle school, and even across town, as she headed to work cleaning houses. A second vehicle soon joined the first.

She made her way to a midtown Tulsa home for her first client of the day, but when she pulled into the driveway, she was blocked in by the same two vehicles that had been tailing her.

The mother knew her rights and remained in her car until the officers, whose vests read ICE and HSI, threatened to shatter her window. As soon as she got out of the vehicle, officers detained her and took her to the David L. Moss Criminal Justice Center, better known as the Tulsa County Jail.

When she was taken, sirens wailed and neighbors began to gather in commotion. Thirty-three-year-old Stewart Jones, the house cleaning client and a witness, estimated that the encounter lasted less than 10 minutes, and described one of the agents coming to the door after detaining the mother to give Jones her belongings.

“You’re safe now, we’ve detained this driver,” Jones recalled an agent saying to him after handing off her car keys. “But you’re not targeting a criminal. You’re targeting a mom of four,” he remembers responding.

ICE and DHS refused to comment for this story on their tracking and deportation of the single mother or their protocols for tracking and detaining people suspected of being in the United States without valid documentation.

The mother, whose name has been anonymized out of fear of retribution and harassment for herself and her family, cleaned houses in Tulsa for the past six years. She came to the United States from Mexico over 13 years ago, and close family friends—who have also asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution and harassment—described her as having no prior criminal convictions, not even a traffic ticket. All of her children were born in the United States, with the youngest being just three years old.

The family friends, who are now the legal guardians of her children, struggled to track her movement through the system. That morning they reached out to the Tulsa Police Department, who said they had no involvement in the arrest, and within days the mother was told she was being taken to Texas, which the family friends found out from someone she had met while detained at David L. Moss.

After six days of detention, during which the family friends obsessively checked Dallas facilities to locate the mother, she called to inform them that she had been taken to the southwestern border town of Del Rio, Texas, and was already on a bus to reunite with family in Mexico.

These accounts of the single mother’s detention and deportation shine a light on Immigration and Customs Enforcement tactics in Tulsa, which resemble those used in so-called “sanctuary cities” around the country. And as the agency continues to make alliances across Oklahoma to increase the speed and volume of its deportation campaign, Tulsa County is proving itself an essential cog in the federal government’s deportation machine.

ICE & Oklahoma: A History of Collaboration

Immigration detentions in Oklahoma are on the rise. According to data collected by the Deportation Data Project, the number of detentions in 2025 nearly doubled the number of detentions in 2023 and 2024 combined. A majority of those detained have no prior convictions or criminal record.

According to the data, 1,994 people have been flagged and booked by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, better known as ICE, across Oklahoma in 2025.1 At least 440 of those passed through the Tulsa County Jail, with 80% having no prior convictions, according to reporting by KOSU.

To date, 27 Oklahoma counties, municipalities and state agencies have signed partnerships with ICE, ranking Oklahoma among the top 10 states for participation and cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. Through what are called 287(g) agreements, local police, sheriffs, and agencies such as the state’s Department of Public Safety can enforce federal immigration law and continue mass deportation orders. Twenty-five of these 27 agreements were signed in the last nine months alone.

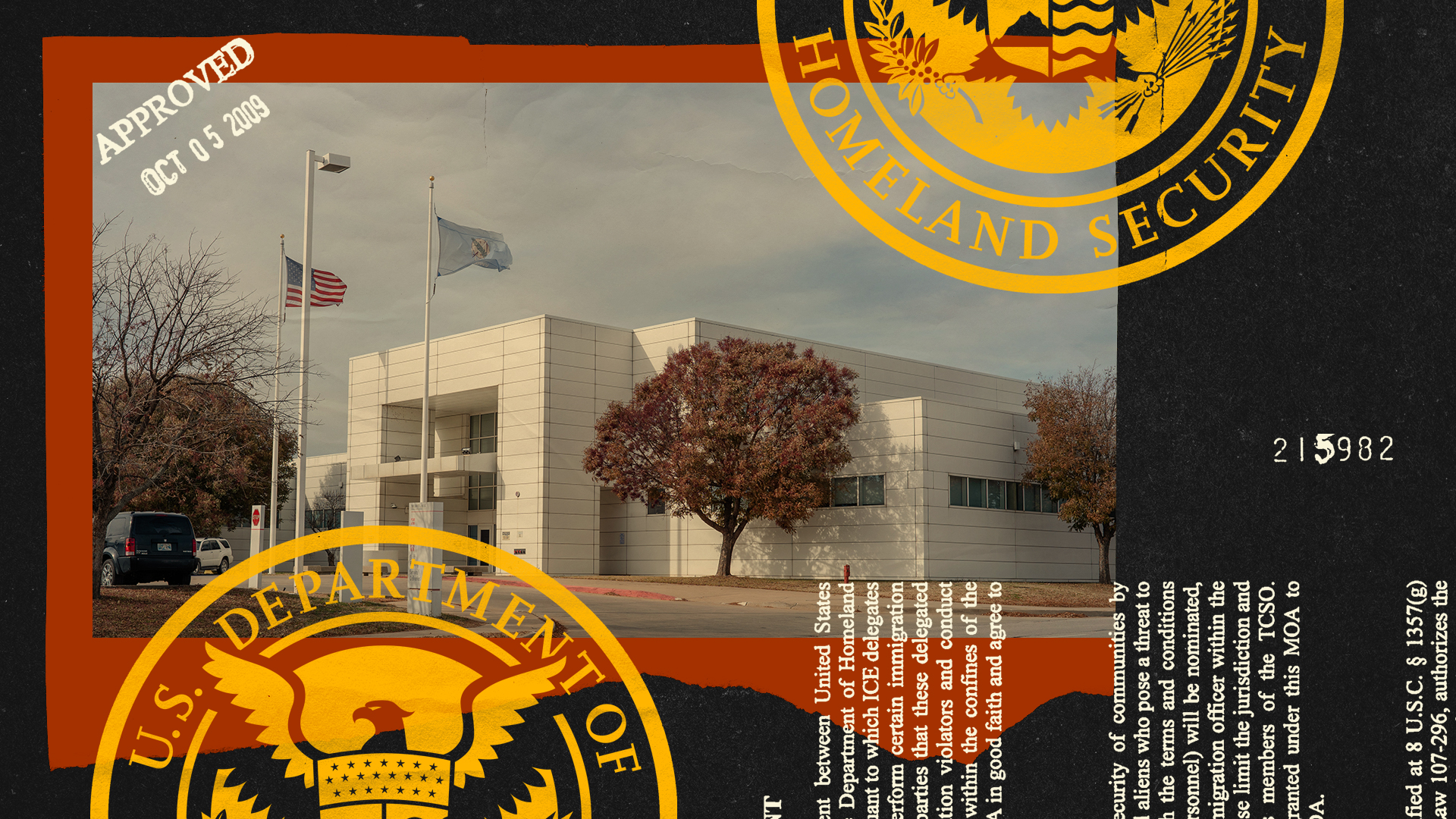

The Tulsa County Sheriff’s Office has one of the longest-standing 287(g) agreements in the state. It predates the Donald Trump administration, going back to 2009, when it was signed by then-Sheriff Stanley Glanz. Current Tulsa County Sheriff Vic Regalado, who is the son of Mexican immigrants, took office in 2016. Regalado renewed his office’s ICE agreements despite facing public scrutiny over rising concerns about racial profiling. Nearly a decade later, the Tulsa County Jail continues to lead the state with consistently high ICE detentions.

When questioned earlier this year by KJRH, Sheriff Regalado claimed his office has no control over who ICE detains. But the reality is more complicated.

The sheriff’s office employs a jail enforcement model through their 287(g), meaning authorized Tulsa County Jail officers are deputized to interrogate people booked for local and state charges about their immigration status and flag them for ICE. The county can also use its own discretion in deciding when to enforce the immigration violations they encounter.

Meanwhile, the Tulsa County Jail serves as a temporary detention facility, leasing out beds to ICE for $75 per person per day. And while the sheriff does not have a say over who ICE arrests and transports for temporary detention at their facility, their service agreement with federal agencies to house detainees awaiting immigration court dates is voluntary.

Tulsa County has the choice to enter into both the 287(g) agreement and the housing services agreement,2 which are continued indefinitely until terminated by one of the agencies. The Tulsa County Sheriff’s Office as well as the Tulsa Board of County Commissioners, both of which are headed by elected officials, prepare and approve these agreements.

While a new long-term contract has not been published,3 adjustments have been made to meet increased demand to house ICE detainees shuttled in from across the state and Dallas. When reached for comment about the status of this service agreement, Tulsa County Sheriff’s Office spokesperson Casey Roebuck said that the sheriff’s office does not currently have a “long-term” housing contract with ICE, but that “under the current agreement, we can hold ICE inmates for up to 72 hours.”

Roebuck also said that the highest number of ICE detainees the county jail can hold is “around 300.”

ICE’s Growing Footprint

ICE’s presence in Oklahoma can be measured beyond its cooperation with state and local governments.

The state ranks seventh in ICE arrests per capita, and also has the ninth-highest rate of ICE arrests at local jails compared to other states, according to data collected in the first five months of the Trump administration by the Prison Policy Initiative. And as detentions and arrests both increase, the local infrastructure necessary to support ICE’s campaign has grown as well.

In recent months ICE has solidified Oklahoma as a stronghold by expanding office space in Oklahoma City, and reopening two privately owned rural detention facilities with a combined capacity of 4,560 beds. The new five-year contract to reopen facilities in Watonga and Sayre that have been vacant for over a decade caused concern in adjacent communities, whose residents must weigh their own ethical unease against the promised economic benefits of these facilities.

But these mass deportation campaigns expand far beyond the incarceration-to-deportation pipeline, and residents with a variety of statuses—from green cards and active work authorizations—are fearful of how the immigration dragnet is sweeping across vulnerable communities.

For example, Oklahoma’s DACA recipients have found themselves mired in uncertainty. Institutions of higher education revoked in-state tuition for nearly 400 students in September, giving roughly a month’s notice for students to pay up or drop out.

Officials feel emboldened to enact such changes in part due to the 2024 passing of House Bill 4156, which created a new state crime of “impermissible occupation,” or what the state defines as being in the country without legal immigration status. While lauded by the legislature as a response to human and drug trafficking, the ACLU and other local advocacy groups like Padres Unidos continue to argue that the law is unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, the Tulsa Police Department has not signed a 287(g) agreement with ICE and has consistently committed to a focus on public safety, which includes protecting all Tulsa residents regardless of their immigration status. Tulsa Mayor Monroe Nichols has been an outspoken critic of HB 4156 since his days in the state legislature, and as mayor-elect promised that the Tulsa Police Department would never cooperate with federal immigration authorities to deport non-criminals.

“Tulsa is one of the safest places to be as an immigrant,” said Lorena Rivas, a local immigration attorney.

And while local authorities have declared a policy of discretion, state agencies have prioritized a display of anti-immigration policy by touting arrest records and crackdowns. Shortly after Trump won reelection in 2024 Governor Kevin Stitt announced Operation Guardian, a comprehensive effort on the part of the state to assist in Trump’s immigration crackdown.

Rivas explained that while roughly half of her cases come from people arrested for unrelated charges before being handed over to ICE, the other half are people detained by state authorities, predominantly the Oklahoma Highway Patrol. In the last three months, joint operations from OHP and federal immigration authorities have resulted in nearly 300 arrests from checkpoints on prominent interstates. The first, set up along Interstate-40 running west out of Oklahoma City, resulted in 125 arrests, with later operations running east along the Arkansas border near Fort Smith, and south near Durant in Bryan County.

Officials indicated that OHP and ICE positioned themselves near weigh stations to inspect and interrogate drivers about their English proficiency and immigration status, broadcasting their commitment to collaborate with federal immigration authorities. Further, KOSU reported that at a press conference, Oklahoma Public Safety Commissioner Tim Tipton encouraged law enforcement leaders nationally to look to Oklahoma as a template for how to collaborate with ICE.

Rivas expressed concern that these operations rely on racial profiling. She said many of her clients get pulled over in similar traffic stops and placed in ICE detention, rather than being charged for a traffic citation.

Enforcement Trends and Counterintelligence

Nationally, ICE and DHS have flooded social media with montages of Operation Midway Blitz and Operation Charlotte’s Web, staging hundreds of raids and roving patrols across so-called “sanctuary cities” such as Los Angeles and Chicago. Operations have targeted car washes, Home Depot parking lots, and construction sites, while also profiling pedestrians and pulling over motorists for minor traffic violations. Nationally, ICE has also stationed themselves in the corridors of courthouses staging deportation traps that pick up hundreds who have shown up for routine hearings.

In November, an ICE operation near an Oakland elementary school caused a car crash; the surrounding schools went on lockdown. Similarly, a Chicago pre-K teacher at Rayito de Sol was detained and taken inside a North Center daycare facility. Security footage and videos from witnesses showed armed agents with vests labeled “POLICE” and “POLICE ICE” inside of the school where they wrestled and removed the educator. DHS officials claimed they did not target a daycare and that it was a targeted traffic stop. The educator was released a week later from an Indiana facility and is continuing to pursue her immigration claims in court.

ICE has also been seen disguising themselves as construction workers and using fake job offers to trap day laborers. In August, federal agents in Los Angeles concealed themselves in a truck while an undercover agent posed as a contractor approaching workers seeking employment. In what officials called “Operation Trojan Horse,” Border Patrol agents arrested 16 day laborers at a Home Depot outside of Los Angeles.

As Human Rights Watch described in their recent report on human rights abuses committed by ICE in Los Angeles, many of these raids rely in large part on detaining people based on their perceived race, ethnicity, and national origin, and have been bolstered by the Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo.

Despite some public perception to the contrary, Rivas debunked the assumption that Oklahoma’s status as a red state gives it protection, saying that immigrants living in more rural and car-centric states have an increased likelihood of encountering law enforcement on their commute.

For decades, there has been a consistently high number of people being detained in rural states, according to Rivas. What’s new under this administration, she said, is the speed at which legal proceedings and removals are taking place. The influx of new policy and the elimination of former protections like bond hearings have hindered immigration attorneys’ ability to effectively defend their clients.

U.S. citizens and permanent residents have also been routinely profiled and detained across Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Arkansas. These cases are often underreported, but an Oklahoma family made national headlines in April after about 20 armed federal agents raided their house in the middle of the night. While conducting a search warrant issued for someone else, agents ordered the mother and her three daughters, all U.S. citizens, to stand outside in the rain while they unlawfully searched the house and confiscated belongings including phones, laptops, and cash savings. DHS confirmed that the previous residents were the targets of the raid, but refused to comment further on the actions of the agents.

Enforcement trends seen in “sanctuary cities” have popped up across the state. ICE targeted apartment buildings in Oklahoma City, coming in with a warrant for one person or claiming to do a welfare check, but then attempting to raid the entire building, as they have done in Chicago. Some property managers and employers have pushed back, but communities remain cautious and have prioritized documenting incidents as people across Oklahoma, and the country, continue to encounter immigration enforcement at previous safe havens, such as schools, hospitals, and even churches.

In July, an Oklahoma City father of five posted on Facebook that he was on his way to drop off his son at daycare, just three blocks from home, when he claimed he was boxed in by an unmarked Tahoe. In Facebook messages he described being asked two questions before his window was shattered.

For the single mother in Tulsa, her arrest came just as suddenly. She had no plan in place, but family friends stepped in to take care of her kids.

Stewart Jones, who witnessed her arrest, works as a business assistant in the dental industry and lives with his fiancé. The single mother had been coming to clean their home for over two months, and the couple was blindsided by the events that unfolded that Friday morning.

“It shouldn't take this happening in your driveway,” said Jones. “But the reality of it being thrown right in your face … I needed to figure out what I can do.”

Grit In The Machine

In response to these swift actions, which frequently leave bystanders shaken and confused, many counterintelligence and advocacy groups have resorted to tracking abandoned vehicles in hopes of matching missing people with identifying markers and belongings. Groups also frequently filter and upload ICE sightings and license plates, while disseminating messages from other agencies and officials to provide insight and spread awareness.

Uncertain of what the future holds, families across the country—especially those living in mixed-status households—have begun to prepare plans and assign legal guardians for their children, on the chance that their lives are upended in an instant.

Lorena Rivas, the Tulsa immigration attorney, advises clients to get paperwork and plans in order now, and to consult with an attorney to understand the specific risks that they or their families face.

Rivas said that for families and single parents, a power of attorney letter can appoint someone to be the legal guardian of your children. She advises her clients to carry original identification cards and documents, but also copies, and to draft letters about goods and assets to codify the power to access a bank account or sell major assets like a car or house.4

The Pickup is an independent media company from This Land Press about Tulsa and its culture. We write stories for real people, not AI scrapers or search engines. Become a paying subscriber today to read all of our articles, get bonus newsletters and more.

For clients that have an ongoing immigration case or have started any process with their immigration status, Rivas recommends carrying a copy of any petitions that have been filed, along with any other court documents that can be provided to indicate ongoing status. “While that might not stop them from being immediately arrested, it might slow down an immediate deportation,” Rivas said. Those same immigration laws, she said, also provide a lot of defenses.

In September a mandatory detention policy change swept the nation after the Trump administration overturned legal precedent by eliminating bond hearings. But in the aftermath, hundreds of court cases have been filed with judges ruling in favor of immigrants, including a November decision from the Central District of California ruling the policy unlawful and granting class-action status to all migrants subject to mandatory detention.

Rivas said that while the outlook is gloomy, there are still success stories happening. “Keep on trying, keep the hope alive. Don’t completely give up on our immigration system.”

Footnotes

- The data was collected until July of this year.Return to content at reference 1↩

- The most recent publicly available renewal of the sheriff’s housing services agreement was published in October 2020. Under that agreement, Tulsa County Jail is to provide 10 beds to ICE on a “space available basis” for no more than 72 hours, accommodating for approximately 36 detainees per month. This agreement was adjusted and renewed from its 2016 contract with ICE to provide 200 beds, after ICE holds had trended downwards. But under the Trump administration those numbers have shot back up. Analyzing current government data under the standards established in that October 2020 agreement, the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse estimates that the Tulsa County Jail’s average daily population consistently surpasses the ceiling of their contract with ICE. While the county jail has a capacity of over 2,000 beds, their detention agreement only provides 10 of those beds to ICE. Data shows that for at least one night in fiscal year 2025, Tulsa County held 164 more people for ICE than the 10-bed ceiling. In May, Public Radio Tulsa reported that Assistant Jail Administrator Marcus Berry had counted 230 ICE detainees in jail on April 28, 2025; this was while discussing a new contract with federal authorities that would permit the sheriff’s office to hold up to 300 detainees for an “indefinite” amount of time, similar to its 2016 agreement.Return to content at reference 2↩

- In a statement at a July 2025 meeting of the Tulsa County Criminal Justice Authority Sales Tax Overview Committee, Jail Administrator Stacie Holloway said that the sheriff’s office does not have a new long-term contract, and that the current federal housing rate was being renegotiated from a rate of $75 per day to between $126 and $130 per day.Return to content at reference 3↩

- Rivas added that if you’re a citizen your passport is the strongest document you have. Rivas said getting a passport card and legal residency cards are an essential step.Return to content at reference 4↩