The Pickup is an independent media company doing culture journalism for curious Oklahomans. We write stories for real people, not AI scrapers or search engines. Become a paying subscriber today to read all of our articles, get bonus newsletters and more.

It’s been a wild few years for the cryptocurrency industry.

Citing the 2022 bankruptcy of crypto futures trader FTX, The Atlantic emphatically declared in early 2023 that crypto was over, following an intensive effort on the part of the industry to push itself into mainstream acceptance.

Then Donald Trump got reelected president and cryptocurrencies’ asset prices shot up. Having previously called crypto a scam, Trump did a heel turn in 2024 as he courted the tech right, vowing to make the United States the "crypto capital of the planet." In that year alone the combined value of all digital currencies doubled. Bitcoin, the crypto industry’s poster child, rode to a high value of $118,000 when just two years before it had been valued at $16,000.

The combined market capitalization of crypto is sky-high, and we’ve seen it ingratiate itself into mainstream acceptance by way of America’s financialized economy, which overlaps at times with the machinations of the state. Pension funds in Michigan and Wisconsin are holding bitcoin, the crypto industry contributed $119 million in 2024 to influence federal elections, and Trump himself is earning hundreds of millions of dollars from World Liberty Financial, a crypto company founded in 2024 and owned by a Trump business entity.1

The one thing that’s consistent about bitcoin? The carbon emissions put off by its production. As the digital currency’s asset price fluctuates, its emissions have steadily trended upward. In 2024 the University of Cambridge’s Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index clocked its annualized emissions at 62 megatons, equivalent to that of Serbia. Today it’s on track to produce over 85 megatons.

Enter the state of Oklahoma. In the middle of this 2024 crypto boom, state legislators passed House Bill 3594, which made Oklahoma one of the first states in the country to define legal terminology around crypto. But the law went further than has been publicly reported.

The new law effectively put up a giant billboard for crypto miners, who have been roaming the American countryside in search of the cheap energy, land and running water needed to power their mining operations. And as major tech companies scramble to meet the increased computing needs created by artificial intelligence — a technology whose financial returns remain unproven — these resources are coming under strain statewide.

Now that new law may come to be tested in court, as one town in Oklahoma has found itself at odds with a mine that’s humming right along as it extracts local resources to manufacture its digital currency.

What happens when we let these digital industrialists decide what should happen in the physical world? Oklahoma is about to find out.

That’s Not Very Libertarian Of You

With its origins in the early 2000s as a decentralized currency, it’s hard to imagine a more libertarian concept than bitcoin. Some of its earliest use cases were in black markets like Silk Road, which facilitated the online sale of illegal drugs. When the FBI arrested Silk Road boss Ross Ulbricht2 in 2013 it seized tens of thousands of bitcoin, at that time the de jure currency of the anti-establishment.

But opportunity sometimes creates strange bedfellows, and so in 2024, with crypto’s market capitalization higher than ever, a bitcoin advocacy group helped Oklahoma legislators pass House Bill 3594 into law. Sponsored by Representatives Brian Hill (R-Mustang) and Cody Maynard (R-Durant), and Senators Bill Coleman (R-Ponca City) and Dana Prieto (R-Tulsa), the bill passed quietly through both houses and was signed by Governor Kevin Stitt three months after its initial introduction, establishing the state as one of the friendliest in the country to crypto mining.

“We want this industry to know Oklahoma is open for business," Rep. Hill told a TV station after the new law went into effect. The bill’s passage eluded local and national press coverage, attracting attention only from Forbes. In the months we spent reporting this story, the only sources we found who were aware of the new state law’s existence were cryptocurrency advocates.

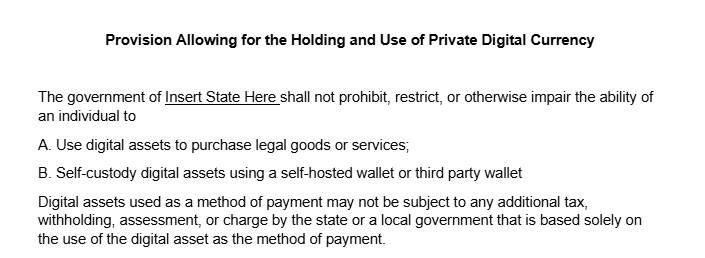

Upon closer scrutiny of the text of the new law, it copies its definitions nearly word for word from the pre-written model policy of the Satoshi Action Fund, a nonprofit dedicated to bitcoin advocacy. Here's a selection of the model policy:

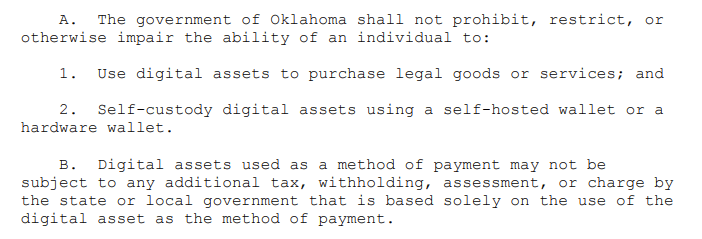

And here's the text of HB 3594, from the state legislature's website:

One day after the bill’s passage, Satoshi Action Fund CEO Dennis Porter3 celebrated it, writing on X that “Bitcoin mining has been under constant attack. This bill promotes #Bitcoin mining in Oklahoma. By protecting the ‘right to mine,’ #Bitcoin gives confidence to companies and investors to operate in Oklahoma, ensuring it can use this new technology to balance the grid, clean the environment, attract local investment, and create rural jobs.”4

The law itself bars restrictions on self-custody of digital assets, ensuring miners have full control over their holdings without third-party interference or regulation. Furthermore, it grants mining businesses the legal right to appeal zoning changes in court, requiring judges to reject any local rules or amendments that discriminate against mining operations.5

But most importantly — and this is the part that’s largely escaped the public’s notice — the new legislation prevents local governments statewide from imposing any requirements on digital asset mining operations that do not also apply to traditional data centers within their jurisdiction.6 This adds burden to counties and municipalities, who are left to their own devices when it comes to dealing with data centers already.

And while the data center requirement in the bitcoin law may seem like a minor technicality, its impact on Oklahoma’s economy and energy infrastructure is potentially significant.

“Oklahoma, especially northeast Oklahoma, has a lot of water and cheap electricity. So we're just kind of naturally a pretty good place for [cryptocurrency mining],” said Dr. Andrew Morin, assistant professor of cyber studies at the University of Tulsa. “It's just an insane amount of electricity that they take.”

Land, Water & Power

Whether they’re building bitcoin mines or data centers, developers have clearly taken notice of Oklahoma. One major data center project in Tulsa County, Project Clydesdale, broke ground recently, while another, Project Atlas, is planned for summer 2026. Each development has prompted a volley of concerns from nearby residents that range from rate hikes on their utility bills to resource use and diminished quality of life.

The likelihood of rate hikes caught the eye of Rep. Amanda Clinton (D-Tulsa), who recently sponsored an interim study in the state legislature to shed more light on utility usage by data centers, which can legally be kept secret by non-disclosure agreements.

“If this industry continues to expand and proliferate at this rate, my fear is that it is a $10 to $12 increase right now. In a year or two, maybe it's another $10 or $12 increase. Another year it's another $10 or $12 increase and pretty soon we may be paying $100 extra dollars a month for electricity,” Clinton said. “I just don’t believe that consumers should have to foot the bill for the expansion of this technology when Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple — I mean these are multi-billion, trillion-dollar companies — they are perfectly capable of picking up that cost themselves, in my opinion.”

At a September hearing of the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, Matthew Horeled, a vice president at Public Service Company of Oklahoma, testified that commercial and industrial growth is being fueled by new customers coming on to the system with electric needs far greater than what PSO has handled in the past.

“PSO has signed a Letter of Agreement with a new customer that will eventually result in a load of over 1,000 [megawatts].7 For most of PSO’s history, the largest single customer was 130 [megawatts],” said Horeled.

It’s not clear how many of these new customers are bitcoin mines or data centers. For the enormous amount of power these developments use, it’s difficult to tell how many are even operating in the state. During her interim study Clinton asked the federal Department of Commerce and couldn’t get a straight answer.

“Data centers [fall] under a particular NAICS code that also covers web development and other different web and online services that are not [operating] nearly at the scale of a hyperscale data center,” Clinton said. “So they get lumped into this business classification that is very broad.”

We reached out to Storm Rund, the president and executive chairman of Oklahoma Bitcoin Association, who estimated that Oklahoma is currently home to between 25 and 30 active commercial cryptomining operations. Rund said they vary dramatically in scale, from small commercial setups that use around 300 kilowatts, to the largest facility, the Polaris Technologies site in Muskogee, which was estimated to use between 200-300 megawatts before plans for expansion in 2024.

The differences between a bitcoin mine and a data center have less to do with their infrastructure — at the end of the day, they’re both essentially warehouses full of computers that run around the clock — and more to do with who benefits from their operations.

Hyperscaled tech companies like Google maintain large data centers, but companies outside of the tech industry do as well. HR provider Paycom operates two data centers in Oklahoma City, for instance. These companies have customers, of course — because of these data centers you can use Gmail or quickly process a payroll. But a bitcoin mine’s operations don’t support a product or a service for customers — they add to the speculative asset portfolio of its ownership.

This distinction likely doesn’t matter to Oklahoma’s vanguard of energy providers, who appear eager to meet the demands of these new data center clients whether they mine cryptocurrency or help you book your next flight. And while the unprecedented electricity use is considerable, the implications for our water supply are serious as well.

This concern was top of mind for Clinton, whose interest in water prompted the interim study on data centers in the first place.

“In the Tulsa area … we're probably okay on the water side because most usually the water for these data centers is supplied by municipalities and most of our municipalities in northeast Oklahoma draw from surface water,” Clinton said.

“But for other parts of the state — say Oklahoma City-area further west — if they are proposing data centers that use groundwater … that's kind of skating on thin ice. Because we're already removing water from the aquifers faster than the recharge rate, and if we start doing it even faster, those aquifers could cave in. And when they're gone, they're gone,” Clinton said.

Another finding Clinton made was that the private sector appears to be working directly with municipalities rather than the state of Oklahoma to develop these projects. Rural governments can be particularly disadvantaged when it comes to negotiating with developers over the installation of data centers, as they may lack the resources necessary to properly vet these high-tech proposals.

“A lot of [rural] mayors and city councils are volunteer positions,” Clinton said. “The state has a very light hand, if at all, in this industry.”

These factors — the industry’s need for natural resources, the state’s preemptive stance against regulation and potentially outmatched rural governments — are colliding right now in Muskogee, where Polaris, the state’s largest bitcoin miner, is suing the city after the city council there voted to annex the land in the industrial park where the mine operates.

Hard Water In Muskogee

Since its expansion in 2024, the Polaris facility has grown to consume approximately 400 megawatts of electricity per hour, an amount that could power roughly 400,000 residential homes for the same amount of time. The mine also draws heavily on local resources. The city says that the mine uses 6% of the city’s water daily and is the largest user of energy by far.

Noise pollution has also become a persistent complaint from nearby residents who say the constant low-frequency hum from the mine has impacted their communities and quality of life.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter, The Talegate

After a Muskogee resident filed a complaint with the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality, an inspection of the mine in March uncovered ten violations with seven violations labeled as minor deficiencies, and three labeled as significant.8 All of this has prompted broader concerns about whether mining facilities truly contribute to local economies, or simply extract resources.

Despite the significant public outcry and environmental degradation, it seems that the people of Muskogee will have a difficult time fighting Polaris’s lawsuit, thanks to Oklahoma’s new bitcoin law. The suit calls on the court to block the city council’s annexation vote based on a lack of notice and specifically cites the 2024 bitcoin law’s data center requirement.9

It seems unlikely that the city of Muskogee will be able to annex or tax the Port of Muskogee, where the Polaris mine is located, even as the mine draws on resources and negatively impacts its citizens. While the city continues its efforts to annex the port, the state government has made it clear where it stands on crypto mining, and the language of HB 3594 seems to leave little room for local municipalities to exercise authority over the industry.

Are These Heavy Energy Users Even Worth It?

With HB 3594 forcing the state out of a regulatory role preemptively, local governments are left to make their own cost-benefit evaluations about opening their doors to mining operations and their older cousin data centers. And while these developments no doubt create opportunities for the contractors who build the facilities, the environmental costs and full-time job creation have politicians across the state singing different tunes.

“Bitcoin mining can strengthen our power grid, bring new investment, and create high-tech jobs,” said a statement sent by the office of Rep. Maynard, one of the sponsors of Oklahoma’s bitcoin bill. “HB 3594 keeps Oklahoma on the side of freedom, defending the right of every Oklahoman to participate in the Bitcoin [sic] economy and laying the groundwork for our state to lead America’s next chapter of financial innovation.”

“We have had a lot of conversation about not basing our economic future on data centers, and a lot of that’s because, in addition to the environmental issues, they typically aren’t massive job creators,” Tulsa mayor Monroe Nichols said to the Tulsa World in May. “I think there’s a space for some of that activity. Data centers as a whole I don’t think will ever be a kind of critical piece of our economic development effort. You know, I think in some cases, [they] may be a necessary evil.”

Over the summer Governor Stitt traveled to Chickasha to tout a proposed $3.5 billion electricity plant that will reportedly deliver behind-the-meter energy for high-load users, including data centers.

An investment of that scale is essentially a bet on the use of artificial intelligence driving a huge demand for power. But if artificial intelligence underwhelms, or if the systems powering it ultimately require less computing power than projected, or if the tech industry can’t figure out how to make a return on these big data center bets, local governments that sign big development deals could be taking on major risks. Why overbuild for an industry obsessed with efficiency?

“Oklahomans, and particularly municipalities … need to take this very slow and be very conscientious and very discerning when they're making a decision about whether or not this is the industry they want in their town,” said Clinton.

What’s In A Name?

Perhaps it’s possible that we’re overlooking something very simple here, which is the definition of the word “mine.” Here are a few:

a pit or excavation in the earth from which mineral substances are taken

to get (something, such as ore) from the earth

to extract from a source

None of these describe bitcoin mining. Bitcoin is not part of nature, and you can’t hold it in your hand. At the end of the day, it’s an unevenly regulated speculative financial asset, whose owners have gone to a great deal of trouble to ingratiate it and other cryptocurrencies into our economy.

To call it “mining” is to bring to mind images of natural resources and jobs. In reality, it burns up the former and creates as little of the latter as possible. Unlike the mining industries of the past that relied on human labor for extraction and manufacturing, bitcoin mining is entirely digital, and depends on an enormous number of computer servers and a handful of specialized workers whose job it is to keep those computers running efficiently.

While both data centers and crypto mines use unprecedented amounts of electricity, water, and land to operate, the most critical distinction between the two remains in their output. Netflix’s data centers let you stream a movie on your tablet, but a cryptocurrency mine exists for its owners’ self-enrichment. Why should the public should give crypto miners public dollars and resources to manufacture their own wealth, in exchange for a few jobs and increased utility bills?

“I don't want to say I'm pessimistic,” said Dr. Morin, the TU professor. “I'm skeptical of cryptocurrencies and decentralized finances. So, you know, generally speaking, it's just a solution looking for a problem. So I don't really think there's necessarily a need for it.”

Footnotes

- One more hit here: President Trump’s top housing regulator has recently pushed for banks to be able to count cryptocurrency as an asset in the mortgage application process.Return to content at reference 1↩

- Ulbricht was pardoned from a double life sentence by President Trump earlier this year.Return to content at reference 2↩

- Neither Dennis Porter nor the Satoshi Action Fund responded to requests for comment.Return to content at reference 3↩

- Satoshi Action Fund has also been directly involved in passing similar deregulatory cryptocurrency legislation in at least three other states: Arkansas, Montana, and Louisiana.Return to content at reference 4↩

- Another notable aspect of the law is that it allows Oklahomans to operate home crypto mining operations in residential zones, as long as they are in compliance with local noise ordinances.Return to content at reference 5↩

- It also prevents the Oklahoma Corporation Commission from establishing a rate schedule for digital asset mining that creates discriminatory rates for digital asset mining businesses.Return to content at reference 6↩

- 1,000 megawatts is enough to power approximately a million residential homes for one hour.Return to content at reference 7↩

- Though details about the specific nature of these violations have not been fully disclosed, it was noted that the site had “no measures to contain or stop sediment” from leaving the site, and that a majority of the area failed to have proper stabilization measures.Return to content at reference 8↩

- A hearing for the lawsuit was scheduled for August 29, but was called off as the city and Polaris engaged in negotiations. However, the city of Muscogee claims the morning after the council meeting between the two, Polaris filed an amended petition against the city. In direct response to the lawsuit, the city voted on Sept. 8 to rescind its annexation of Polaris’ property only to restart the process again and Polaris has confirmed that its litigation efforts will continue. A new court date has not yet been set.Return to content at reference 9↩